Rupture Field Theory

A Practice-Based Theoretical Framework

Quinn Jacobson

Draft for Trilogy — March 2026

Rank asked why the artist so often avoids clinical neurosis when he is so much a candidate for it because of his vivid imagination, his openness to the finest and broadest aspects of experience, and his isolation from the cultural worldview that satisfies everyone else. The answer is that he takes in the world, but instead of being oppressed by it he reworks it in his own personality and recreates it in the work of art. The neurotic is precisely the one who cannot create—the 'artiste-manque,' as Rank so aptly called him. We might say that both the artist and the neurotic bite off more than they can chew, but the artist spews it back out again and chews it over in an objectified way, as an external, active work project. The neurotic can't marshal this creative response embodied in a specific work, and so he chokes on his introversions. The artist has similar large-scale introversions, but he uses them as material.

— Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death (1973, p. 49)

Introduction

The question Becker raises here is not merely psychological. It points toward something that practitioners who have worked within destabilizing material recognize but rarely find adequately named: there is a structure to transformation, and that structure is not automatic. It depends on conditions. It fails under certain pressures. And what it produces is neither comfort nor resolution—something that might more accurately be called survival through symbolic form.

Rupture Field Theory attempts to name that structure.

The theory proposes that encounters with existential rupture initiate a recognizable psychological and creative sequence. Rupture occurs when inherited symbolic frameworks fail to contain destabilizing awareness. These disruptions may arise through encounters with mortality, traumatic experience, historical violence, or moments when cultural meaning structures lose their stability. Awareness of mortality, in particular, has long been recognized as a central destabilizing force in human psychology and culture (Becker, 1973).

Most individuals respond to such destabilization through defensive strategies that restore symbolic stability. Research in Terror Management Theory demonstrates that reminders of mortality frequently lead individuals to reinforce cultural worldviews and identities that buffer them from existential anxiety (Greenberg, Pyszczynski, & Solomon, 1986).

Artists, however—by which this theory means practitioners who have developed specific containers for destabilizing experience through training, discipline, and habit—often respond differently. Rather than closing rupture through denial, they frequently remain within destabilizing awareness long enough for transformation to occur. Through creative practice, destabilizing experience is reworked, externalized, and metabolized into symbolic form. What might otherwise produce psychological paralysis becomes material for artistic creation.

Not always. Not inevitably. And never without cost.

Rupture Field Theory attempts to describe the conditions under which this transformation becomes possible, name the phases through which it moves, and identify where and why it can fail.

Epistemological Position

Rupture Field Theory does not emerge from laboratory conditions or clinical observation. It emerges from artistic practice: from decades of working within photography, painting, and critical writing at the intersection of mortality awareness and symbolic form. It belongs to the tradition of practice-based research—a mode of inquiry in which knowledge is generated through and alongside the act of making, where the practitioner's embodied experience functions as both method and data (Sullivan, 2005).

This is not an apology for the theory's origins. It is a statement of its epistemological ground.

Practice-based theoretical frameworks occupy a legitimate and distinct position within qualitative and arts-based research. They do not seek to establish universal mechanism or predictive causality. They propose recognizable structures—patterns that practitioners, therapists, scholars, and artists may inhabit, test against experience, dispute, and refine. Their validity is not measured by experimental replication but by what Eisner (1991) called structural corroboration: the degree to which a framework illuminates experience that was previously unnamed or inadequately described.

RFT makes no claim to explain why rupture becomes creative expression in every case, or to identify the artist as a categorically different kind of human being. It describes a recognizable pathway through which transformation can occur, names its phases, and proposes the conditions that make passage possible. It is offered as a conceptual map, not a predictive mechanism—and the distinction matters.

A conceptual map does not tell you where you will end up. It shows you the terrain.

Theoretical Context

Rupture Field Theory emerges at the intersection of existential psychology, psychoanalytic thought, trauma theory, and creative practice. Each of these traditions contributes to the framework while leaving a gap that the others partially fill.

Becker, Rank, and the Psychology of Artistic Transformation

Ernest Becker's work established that awareness of mortality produces profound and largely unconscious tension within the human condition (Becker, 1973). Drawing directly on Rank, Becker argued that culture itself functions as a system of symbolic immortality projects—structures of meaning that buffer individuals from confrontation with their own finitude. Terror Management Theory later developed these insights empirically, demonstrating that mortality salience leads individuals to defend cultural belief systems with increased intensity (Greenberg et al., 1986).

But the artist complicates this picture. Otto Rank, in Art and Artist (1932), argued that the artist's fundamental task is not self-expression but world-creation: the construction of a symbolic reality capable of containing what ordinary experience cannot hold. The artist does not merely transform anxiety—the artist builds vessels. This distinction is critical and often overlooked in readings that emphasize only the therapeutic dimension of creativity. For Rank, artistic creation is not primarily about the creator's psychological wellbeing; it is about the construction of a symbolic world that can hold more than inherited frameworks provide.

RFT extends this insight: the capacity for symbolic transformation is not only psychological. It is material, technical, and learned. It depends on having developed the practice of building containers.

Terror Management Theory and Its Limits

TMT research consistently demonstrates that when mortality is made salient, individuals reinforce their cultural worldviews, increase their investment in symbolic immortality projects, and derogate those who threaten their meaning systems (Greenberg et al., 1986; Solomon, Greenberg, & Pyszczynski, 2015). This body of work has been enormously productive in documenting the defensive functions of culture.

What TMT describes less precisely is the generative pathway: the cases in which mortality salience does not produce defensive closure but initiates symbolic transformation. RFT addresses this gap by proposing a structured sequence through which rupture—including mortality awareness—can be metabolized into form. TMT maps the defensive response. RFT attempts to map its alternative.

Post-Traumatic Growth: Points of Contact and Departure

The post-traumatic growth tradition of Tedeschi and Calhoun (1996, 2004) represents the most empirically developed framework for understanding positive psychological transformation following rupture. PTG documents the possibility of growth along dimensions including personal strength, existential-spiritual change, and appreciation for life following adverse experiences.

RFT shares with PTG a fundamental orientation: that destabilizing experiences need not only produce damage. But RFT departs from PTG in several significant ways.

PTG tends toward growth as measurable outcome. RFT insists on provisionality: what emerges from rupture is not stable wisdom but unstable meaning, subject to the next disruption. PTG research largely addresses trauma survivors as a population. RFT is specifically concerned with practitioners who deliberately inhabit rupture as a creative and ethical practice—not merely those who encounter it unwillingly. Perhaps most critically, PTG has been critiqued for implicitly suggesting that the correct response to rupture is growth (Sumalla, Ochoa, & Blanco, 2009). RFT refuses this pressure. Transformation through symbolic form is one possible outcome of rupture, not a prescription for how rupture should be managed.

Containment: Winnicott and Bion

Donald Winnicott's concept of the holding environment—a relational structure that allows difficult experience to be processed rather than defensively rejected (Winnicott, 1965)—describes the interpersonal conditions for psychological transformation. W. R. Bion (1962) theorized a deeper structural version of this process: the container-contained relationship as a fundamental structure of thinking itself. Raw, unprocessed experience—what Bion called beta elements—must be held within a container capable of transformation before it can become thinkable symbolic material. In the absence of adequate containment, raw experience overwhelms the psyche and produces not thought but evacuation: projection, acting out, breakdown.

Within artistic practice, the studio, the darkroom, the page, or the ritual of making functions precisely as this container. Creative work becomes the vessel that allows rupture to remain present long enough for transformation to occur. This is not metaphor; it is a functional description of what containers do.

Trauma, the Body, and Somatic Metabolization

Bessel van der Kolk's work on trauma and the body (2014) introduces a dimension that purely cognitive or symbolic theories of transformation tend to underweight. Traumatic experience is not stored as narrative memory; it is stored somatically, in the body's ongoing physiological response to threat. Metabolization is therefore not only a cognitive or symbolic process. It involves the body—breath, posture, sensation, the physical act of making.

This has direct implications for RFT's account of metabolization in Phase Two. The practitioner holding destabilizing material is not holding it only cognitively. The studio practice—the physical handling of materials, the repetitive motion of printmaking, the stillness required for long exposure—is also a somatic practice of containment. The body is part of the vessel.

Being-Toward-Death and the Pressure of Finitude

Heidegger's analysis of being-toward-death in Being and Time (1927/1962) provides the philosophical ground for RFT's insistence on mortality awareness as the primary initiating rupture. For Heidegger, the authentic confrontation with finitude is not morbidity but the condition for genuine existence: only in facing death's inevitability does life acquire the pressure that makes chosen action possible. Inauthenticity, by contrast, is the flight into das Man—the anonymous they-self that absorbs individual anxiety into collective noise.

RFT extends this into creative practice: mortality awareness functions as the initiating pressure for symbolic transformation when it is held rather than refused. The artist who remains with finitude—who does not look away—discovers not transcendence but the irreducible weight that makes the work matter.

The Rupture Field Model

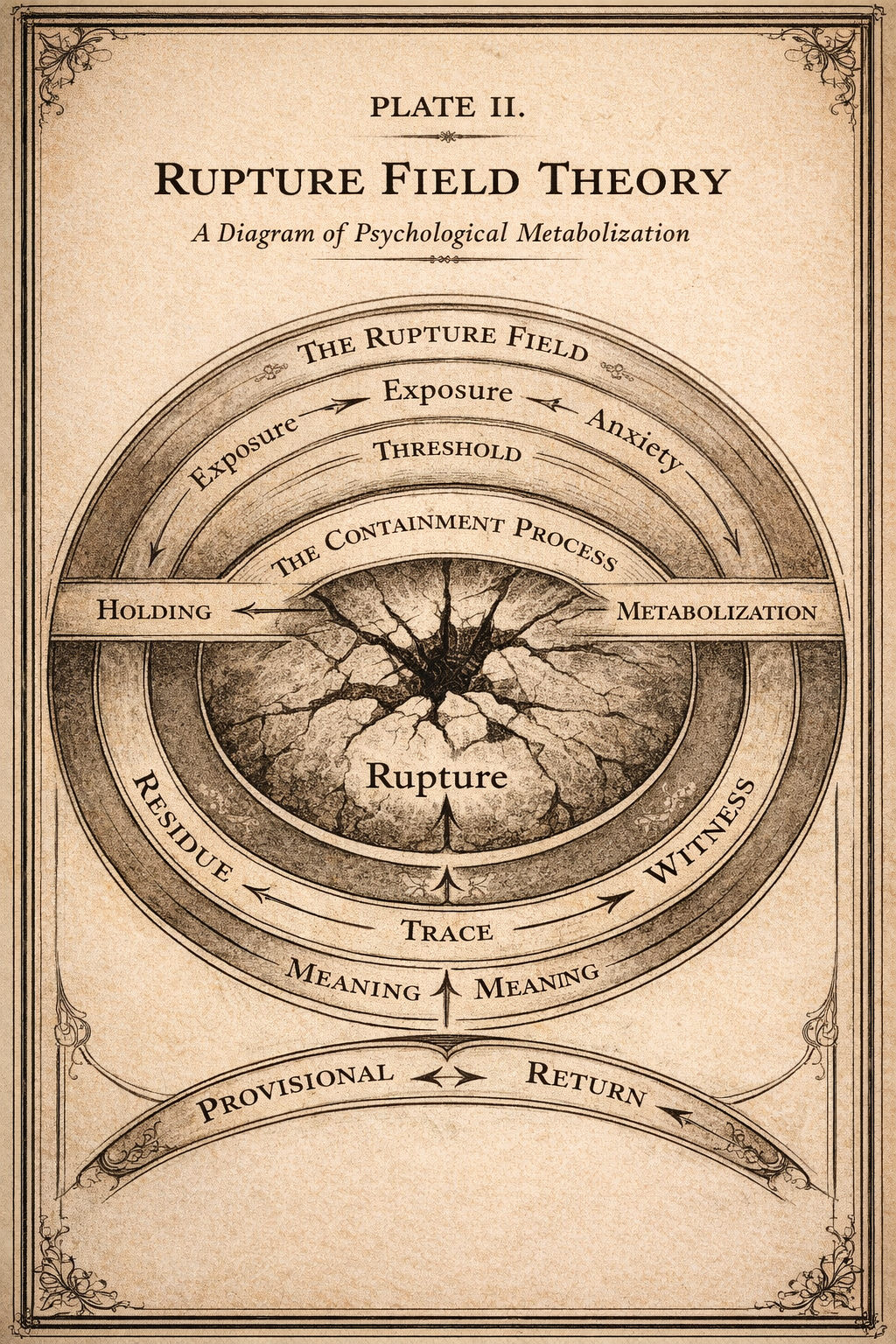

The Rupture Field Model describes the psychological and creative phases through which destabilizing experiences are metabolized. These phases trace a movement from disruption through transformation to integration, and the sequence is cyclical rather than terminal.

Three broad phases structure the model. Not all individuals complete each phase. The process can arrest at any point. Completion does not produce resolution; it produces provisional meaning and return to a destabilized world that will rupture again.

Phase One: Disruption

Rupture — Exposure — Anxiety — Threshold

The first phase marks the collapse of previously stable symbolic structures.

Rupture occurs when inherited frameworks of meaning fail to contain destabilizing awareness. Encounters with mortality, traumatic experiences, historical violence, or worldview collapse may trigger this disruption. Not all ruptures are equal: their intensity varies with the nature of the encounter, the individual's prior history with destabilizing material, and the cultural and material conditions in which the rupture occurs. The theory does not flatten this variation.

A critical distinction within rupture itself must be named: the difference between acute rupture and ambient rupture.

Acute rupture arrives as an event: a death, a diagnosis, an encounter with historical violence, or a sudden collapse of a worldview previously held as stable. It has a before and an after. The disruption is locatable in time.

Ambient rupture operates differently. It does not arrive as a single event. It accumulates as a texture of daily existence—a sustained pressure that gradually makes inherited frameworks untenable without producing a discrete moment of collapse. Climate change is the paradigmatic example of ambient rupture in the contemporary world: it does not rupture you once; it ruptures you continuously, without resolution, at a pace that makes both acute response and gradual adaptation difficult. Political disintegration, economic precarity, the erosion of cultural narratives about progress and safety, the slow violence of systemic inequity—these are ambient ruptures. They do not ask for a single creative response. They ask for a practice of sustained metabolization that has no clear endpoint.

This distinction matters for how each type of rupture moves through the model. Acute rupture tends to produce a recognizable threshold moment—a point at which the individual either retreats defensively or moves deeper. Ambient rupture rarely offers such a clean threshold. Instead, it produces a slow erosion of containment: the vessel does not shatter but gradually loses its integrity. The practitioner working in conditions of ambient rupture must not only metabolize specific material but continually repair and rebuild the container itself. The creative practice becomes not merely a response to rupture but an ongoing structure of resistance against chronic destabilization.

Most people alive today are working within ambient rupture. The contemporary world does not require extraordinary encounters with mortality to generate existential destabilization; the ordinary conditions of being alive and paying attention are sufficient. Wars visible in real time on personal devices. The measurable acceleration of ecological grief. Political frameworks that no longer provide coherent meaning. Economic structures that make provisional stability feel permanently out of reach. These are not exceptional conditions requiring exceptional responses. They are the background of daily life, and the inherited symbolic frameworks—progress, national identity, the promise of continuity—are visibly failing to contain them.

Rupture Field Theory is therefore not a theory about extreme experience. It is a theory about the ordinary contemporary condition of being alive within destabilizing awareness—and what becomes possible when that awareness is held rather than refused.

Following rupture comes exposure. Previously hidden or suppressed dimensions of reality become visible. Assumptions that once structured experience lose their stability. What was background becomes unbearable foreground.

Anxiety emerges as the organism confronts the instability of its symbolic world. Familiar frameworks no longer provide psychological containment. This is not anxiety as minor discomfort; it is anxiety in the existential register—the raw encounter with groundlessness.

The sequence arrives at a threshold. At this point individuals face a decisive moment: they may retreat into defensive denial, restoring symbolic stability by rejecting destabilizing awareness; or they may move deeper into the rupture. This threshold determines whether rupture closes defensively or becomes generative.

The conditions that determine which way this moment resolves are addressed in detail in the following section on threshold conditions.

Phase Two: Processing

Holding — Metabolization — Residue — Trace

This phase represents the psychological hinge of the entire process. It is also the least visible phase—it takes place largely within the practitioner's interior and the enclosed space of creative practice. It cannot be seen from the outside, which may be why it is the phase most frequently undertheorized.

Most individuals resolve rupture through defensive mechanisms that restore symbolic stability (Greenberg et al., 1986). These responses reduce anxiety but prevent deeper transformation. The generative pathway requires something different: holding.

Holding refers to the capacity to remain within destabilizing awareness without prematurely resolving it. The concept draws on both Winnicott's holding environment and Bion's container-contained structure (Bion, 1962; Winnicott, 1965)—the ability of a container to absorb raw, unprocessed experience without retaliation or collapse, allowing it to remain present long enough for transformation to begin. Artists frequently create such environments through studio practice, writing, dialogue, ritual, or contemplative attention. These practices allow destabilizing material to stay present rather than being expelled.

The body participates in holding. The physical discipline of a practice—the repetitive motion, the handling of materials, the regulated breath of close attention—is part of the somatic container (van der Kolk, 2014). Holding is not only psychological.

Through metabolization, fragments of experience begin to reorganize internally. Emotional, cognitive, and somatic elements interact within creative practice, gradually transforming raw experience into workable material. The term metabolization is used deliberately as a biological metaphor: just as the body breaks down and reconstitutes ingested material, the practitioner's process breaks down the raw substance of rupture and reconstitutes it as something the psyche can use. This process cannot be accelerated without loss.

What remains becomes residue—the psychological imprint left by rupture that has been processed but not yet given form.

From this residue emerges trace.

Trace is the most original concept within this framework, and the most precise. It names the early symbolic formation that begins to coalesce from metabolized experience before it has stabilized into fully articulated expression. Trace is not yet meaning. It is the shape of meaning becoming possible.

The concept resonates across several intellectual traditions without belonging entirely to any of them. Derrida (1967/1978) theorized the trace as the mark of difference that enables meaning—the irreducible presence of absence within every act of signification. Levinas (1969) used trace to describe the mark left by the Other's passage, the ethical demand that cannot be fully thematized or contained within one's own system. Within forensic analysis, a trace is what remains after the event: evidence of presence without presence itself.

RFT's use of trace draws on these resonances while departing from them. Here, trace is generative rather than merely indicative. It is not evidence of what has passed but the first intimation of what may yet form. It is the moment in the studio when the practitioner begins to sense—before consciously knowing—that something is taking shape. The first mark on a surface that feels necessary rather than willed. The image that recurs without yet having been made. The phrase that interrupts sleep.

This is why trace cannot be rushed. Post-traumatic growth research tends to move directly from processing to measurable outcome. RFT inserts the trace as a liminal moment—a threshold state of becoming-form that is significant in itself, not merely as a waystation to expression. To rush past trace is to foreclose the possibility of what the rupture was capable of generating.

Langer's analysis of symbolic form in Philosophy in a New Key (1942) offers a complementary framing: before art is statement or communication, it is the felt sense of form—the intuition of significant structure that precedes its articulation. This felt sense is what RFT calls trace.

Phase Three: Expression and Integration

Form — Witness — Provisional Meaning — Return

As internal reorganization stabilizes, trace becomes form. Form represents the moment when symbolic expression is externalized in a specific medium: an artwork, a theoretical framework, a narrative structure, a ritual practice. Form is not the end of the process; it is the moment when the internal becomes available to encounter.

Through witness, these expressions are encountered by others. What began as private experience enters a shared symbolic world. This is not primarily about audience reception—though reception matters—but about the work's capacity to function as testimony. Art that witnesses does not perform resolution; it presents the rupture in stabilized symbolic form, making it available for encounter without pretending to resolve it.

From this encounter emerges provisional meaning. The practitioner begins integrating rupture into an evolving understanding of identity, purpose, and existence. The word provisional is not hedging. It is the theory's most important ethical commitment: meaning remains open to revision. It does not seal the wound. It does not transcend the problem. It creates livable ground.

Return marks reintegration into lived life with a transformed—not healed, not resolved, but transformed—orientation toward reality. The practitioner returns to the world that ruptured them, carrying the trace of what they have made from it.

The Threshold: Enabling Conditions

The threshold moment—the decision point between defensive closure and generative passage at the end of Phase One—is the most consequential moment in the Rupture Field Model. It is also the point the theory must account for most honestly, because it is where the risk of circular reasoning is highest.

A theory that defines artists as people who transform rupture, then explains that artists transform rupture, is not a theory. It is a description. RFT avoids this circularity by proposing a set of enabling conditions—factors that determine whether the threshold is crossable—that are independent of the transformation itself.

These conditions are not prerequisites that must all be present. They are factors that lower the threshold, making passage more available. When multiple conditions are absent, breakdown at the threshold is not a failure of creativity; it is a structural outcome.

Prior Successful Metabolizations

Each completed rupture cycle leaves its own residue: not only the provisional meaning generated but a somatic-cognitive memory that the process is survivable. Practitioners who have worked through rupture before—who have arrived at form from destabilizing material and returned—carry this evidence forward. The threshold lowers with experience. This is partly why younger or less experienced practitioners may be more vulnerable to breakdown at the threshold: they have not yet accumulated evidence that transformation is possible.

An Established Creative Container

Having a practice—a studio, a photographic process, a writing discipline, a ritual of making—means having a vessel already built before rupture arrives. Rupture does not wait for preparation, but the practitioner who has a form to move toward crosses the threshold differently than one who must build the container while the walls are falling. This is why technical discipline in artistic practice is not merely craft: it is the advance preparation of a vessel. Rank's artist builds worlds not only in crisis but in readiness for crisis.

Relational Holding

Winnicott's holding environment does not only describe the mother-infant dyad; it describes any relational structure capable of absorbing and metabolizing anxiety without retaliation or collapse (Winnicott, 1965). Mentors who have modeled the crossing of rupture thresholds, communities of practice that hold the practitioner's identity during destabilization, trusted others who can witness without needing the rupture to resolve—these constitute a relational container that extends individual capacity. No practitioner holds alone, and theories that treat transformation as a solo psychological achievement distort its actual social architecture.

Material and Economic Conditions

This is the condition most systematically absent from existing transformation theories, and its absence is not merely an oversight—it is a distortion that reflects whose experience generates theory.

Holding requires time, space, and the economic permission to remain unproductive during metabolization. These are not equally distributed. A practitioner managing economic precarity, primary caregiving, or ongoing threat cannot afford the same quality of holding that material security provides. Rupture Field Theory does not romanticize the artist's relationship to destabilizing experience. The capacity to remain within rupture long enough for transformation to occur is partly a question of class, race, gender, and structural access to the conditions creative work requires. Any adequate account of artistic transformation must acknowledge that the threshold is not equally available to all.

The Nature and Scale of the Rupture

Not every rupture can be metabolized within a single cycle, or at all. Some encounters with mortality, violence, or worldview collapse exceed any available container. The theory must acknowledge explicitly that the process fails—not because the individual is insufficiently artistic or psychologically weak, but because some ruptures are too sudden, too total, or too uncontained for existing vessels to hold.

The practitioner who breaks under conditions that exceed the container's capacity has not failed the theory. The theory has reached its edge.

The Studio as Vessel: Material Transformation

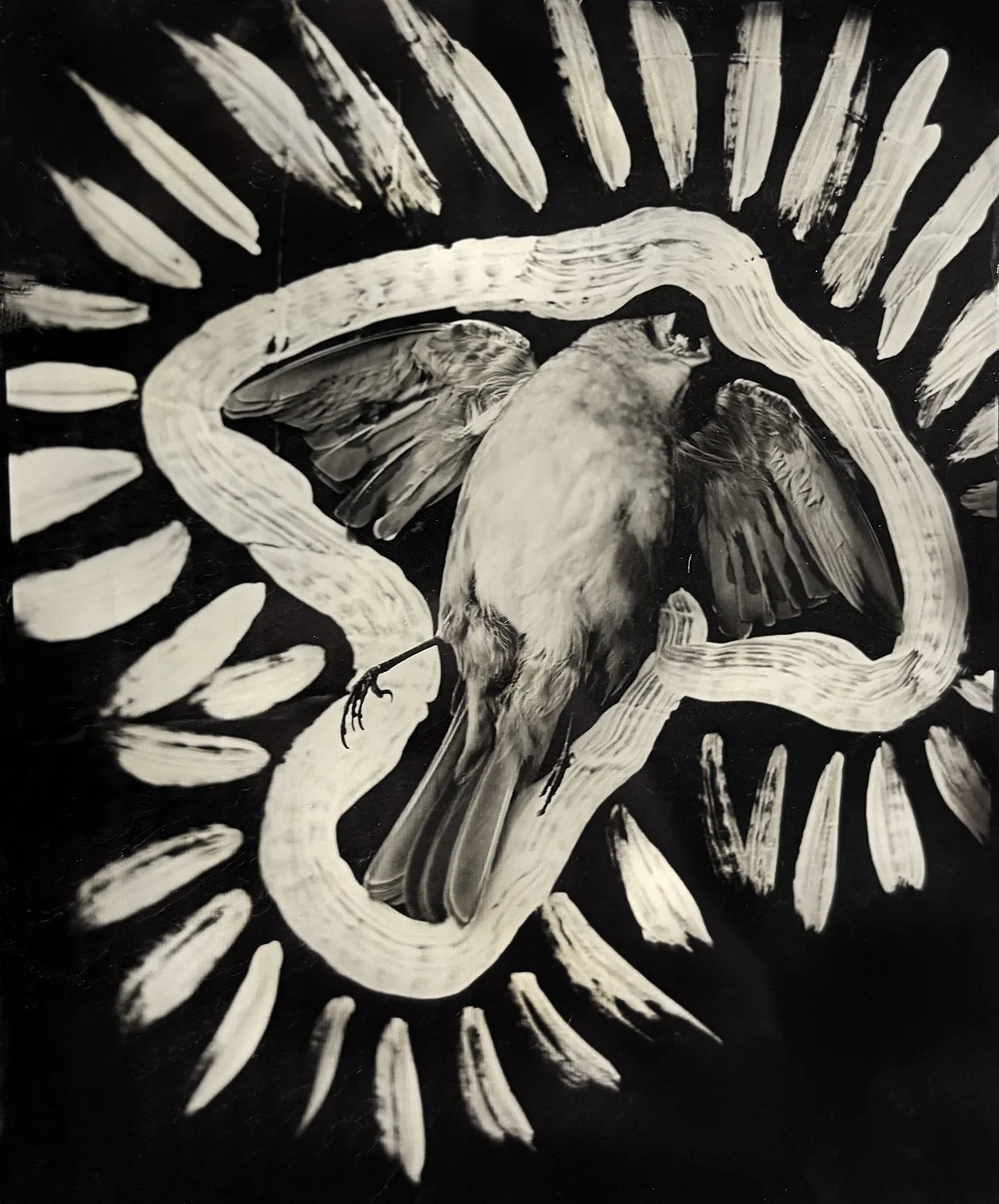

The alchemical resonances within transformation theories are often invoked as metaphor—a borrowing from mystical tradition to suggest the depth of psychological change. RFT situates these resonances differently.

In photographic practice, particularly in 19th-century processes, the alchemical structure is not metaphor. It is the actual phenomenology of the work.

Silver salts held in darkness. Exposure to light that leaves no immediately visible mark—the image is latent, present but unformed. The developer introduced into the contained environment of the darkroom, where the latent image begins to emerge from what appeared to be undifferentiated surface. Fixation: the moment when what has emerged is stabilized, made permanent enough to withstand further light without dissolution. The image that results is neither the original scene nor its absence. It is a trace.

This is not poetic license. The darkroom is, structurally and materially, a rupture field. The photographic process enacts precisely the sequence the theory describes: disruption of stable surface by exposure, containment within a developing environment, metabolization through chemical action, emergence of trace, fixation into form.

Jung's extended analysis of alchemical transformation in Psychology and Alchemy (1944/1968) describes the same structural sequence in psychological terms: prima materia broken down, held within the vas hermeticum, gradually reorganized through the operations of solve et coagula—dissolve and coagulate—until a new, stabilized form emerges. What the alchemical texts described in mystical language is, in photographic practice, a technical procedure enacted with the hands in darkness.

This is not offered as a claim that photography uniquely enacts transformation theory. Every material practice has its own structural analogues—the painter's canvas holding the unresolved image through multiple states, the writer's draft maintaining provisional form through revision. The photographic example is offered as evidence of something more important: the theory does not arrive at practice from outside, imposing a framework upon experience. It emerges from within practice, named by the practitioner who has stood in the dark and watched the image arrive.

The Cyclical Nature of the Rupture Field

The rupture field does not function as a single linear progression that ends once integration occurs. The process is cyclical, and the cycle has no final resolution.

Each provisional meaning eventually becomes another inherited symbolic framework. What was once generative becomes stable, and stability—under new conditions of exposure—becomes brittle. When the next rupture arrives, the newly stable framework fractures, and the cycle initiates again. Human creativity therefore unfolds through repeated cycles of destabilization, metabolization, symbolic expression, and reintegration. Each cycle begins where the last one left its residue.

This is not a pessimistic account. It is an accurate one. Artists do not escape rupture. They learn how to work within it. The accumulated residue of prior cycles—the traces that did not fully resolve, the provisional meanings that held for a time before fracturing—becomes part of the practitioner's material. The work made over a lifetime is not a series of disconnected responses to rupture; it is the accumulated archive of cycles, each one carrying the imprint of those that preceded it.

This cyclical structure also applies to the theory itself. Rupture Field Theory is a provisional meaning generated from the author's own rupture encounters, built upon inherited symbolic frameworks—Becker, Rank, Winnicott, Bion—that will, under new conditions of exposure, fracture and require reworking. This is not a weakness to be corrected. It is the condition of any honest theoretical work.

Functions of Rupture Field Theory

Rupture Field Theory operates across three registers.

Descriptive

The theory describes the psychological arc that practitioners often experience when confronting destabilizing material: mortality awareness, trauma, historical rupture, worldview collapse. It names phases and transitions that are frequently recognized by artists but rarely articulated in frameworks that also take them seriously as intellectual and ethical positions.

Analytical

The framework provides a lens for examining artworks, creative practices, and cultural production as responses to rupture. Artistic forms can be understood as stabilized traces of previously metabolized disruption. This analytical function is not reducible to pathography—the reading of art as symptom of the artist's psychological history. It is a way of understanding what art is for: the construction of symbolic form capable of holding what ordinary experience cannot contain.

Practical

The theory offers practitioners a conceptual map for remaining within existential exposure long enough for meaningful transformation to occur. This includes naming the threshold conditions that make passage possible, identifying the phases through which the practitioner moves, and legitimizing the period of trace—the liminal state of becoming-form that institutional and market pressures frequently rush past.

It also offers practitioners a way to understand breakdown: not as failure of creativity or psychological weakness, but as a structural outcome when threshold conditions are absent or when rupture exceeds the available container's capacity.

Limitations and Scope

Any theoretical framework that does not articulate its own limitations is a framework that cannot be trusted. The following limitations are constitutive features of RFT's current state, not incidental weaknesses pending correction.

Framework, Not Mechanism

RFT is a conceptual framework. It describes a recognizable sequence without fully explaining the causal mechanisms through which metabolization occurs at the neurological, somatic, or psychological level. The threshold conditions proposed here are theoretically derived, not empirically tested. Future practice-based research, qualitative inquiry, and longitudinal study of creative practitioners would be required to test, refine, or contest these conditions.

The Artist/Non-Artist Distinction

The distinction between artists and non-artists within this framework is a distinction of tendency and practice, not ontology. Artists are not a separate category of human being equipped with special transformative capacity. They are practitioners who have, through training, discipline, and habit, developed specific containers for destabilizing experience. The distinction is therefore a gradient that shifts with practice, support, and circumstance—not a fixed category. This must be stated plainly to avoid the theory becoming a mythology of the artist as exceptional.

Survivorship Bias

We see the artists who transformed rupture into work. We do not see—because they are invisible to historical record and to our categories of artistic achievement—the artists who broke, who produced nothing, whose rupture generated not form but silence, illness, or withdrawal. Any theory of artistic transformation that does not account for the dark data overstates its case. RFT acknowledges this silence. The theory describes a possible pathway, not a guaranteed one.

Social and Material Conditions

The threshold section identifies economic and material conditions as enabling factors, but this analysis remains undertheorized relative to the psychological phases. A fuller treatment of the political economy of creative holding—the structural conditions that determine who can access the time, space, and safety that transformation requires—is needed and is acknowledged as beyond the scope of this draft. The universalization of transformation narratives without attention to their social conditions reproduces the omissions of the traditions from which they draw.

The Provisionality of the Model Itself

Rupture Field Theory is a provisional meaning generated from the author's rupture encounters, constructed upon an inherited symbolic framework that will fracture under new conditions of exposure. The model is subject to its own logic. This is not a disclaimer. It is an epistemological position: the theory does not stand outside the process it describes. It is an instance of it.

The central problem this theory addresses is not how to make death bearable. It is what becomes possible—creatively, psychologically, and ethically—when practitioners stop attempting to make it bearable and begin instead to make something from it.

Rupture Field Theory does not offer resolution. It offers a map of the terrain that opens when resolution is refused.

References

Becker, E. (1973). The denial of death. Free Press.

Bion, W. R. (1962). Learning from experience. Heinemann.

Derrida, J. (1978). Writing and difference (A. Bass, Trans.). University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1967)

Eisner, E. W. (1991). The enlightened eye: Qualitative inquiry and the enhancement of educational practice. Macmillan.

Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., & Solomon, S. (1986). The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: A terror management theory. In R. Baumeister (Ed.), Public self and private self (pp. 189–212). Springer.

Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and time (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). Harper & Row. (Original work published 1927)

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery. Basic Books.

Jung, C. G. (1968). Psychology and alchemy (R. F. C. Hull, Trans., 2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1944)

Langer, S. K. (1942). Philosophy in a new key: A study in the symbolism of reason, rite, and art. Harvard University Press.

Levinas, E. (1969). Totality and infinity (A. Lingis, Trans.). Duquesne University Press.

Rank, O. (1932). Art and artist: Creative urge and personality development. Knopf.

Solomon, S., Greenberg, J., & Pyszczynski, T. (2015). The worm at the core: On the role of death in life. Random House.

Sullivan, G. (2005). Art practice as research: Inquiry in the visual arts. Sage.

Sumalla, E. C., Ochoa, C., & Blanco, I. (2009). Posttraumatic growth in cancer: Reality or illusion? Clinical Psychology Review, 29(1), 24–33.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18.

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Winnicott, D. W. (1965). The maturational processes and the facilitating environment. Hogarth Press.