“Some day soon, perhaps in forty years, there will be no one alive who has ever known me. That’s when I will be truly dead – when I exist in no one’s memory. I thought a lot about how someone very old is the last living individual to have known some person or cluster of people. When that person dies, the whole cluster dies, too, vanishes from the living memory. I wonder who that person will be for me. Whose death will make me truly dead?”

Irvin D. Yalom, Love’s Executioner and Other Tales of Psychotherapy

Punished for Embodiment. Half-plate tintype (4.25 × 5.5 in.). December 2025.

Western art has long tried to discipline the body—shrinking it, idealizing it, and denying its animality. This work pushes back. The figure is restrained not for what he has done, but for what he is: a vulnerable organism aware of its own end. The skull waits behind him, already finished with the struggle.

Living With The Dimmer Switch

One of the biggest challenges I face when I talk about Becker, Rank, Zapffe, or Terror Management Theory isn’t that the ideas are too complex. It’s that they’re describing the very psychological machinery that makes them difficult to understand in the first place. (Becker, 1973; Greenberg et al., 1986; Rank, 1932; Zapffe, 1933/2010).

That’s the paradox.

From an evolutionary perspective, human consciousness didn’t just give us language, imagination, and culture. It gave us a problem no other animal has to solve: we know we’re going to die, and we know it with enough clarity to make life unbearable if that awareness stayed fully online all the time (Becker, 1973; Solomon et al., 2015). So evolution didn’t eliminate the problem. It built a workaround.

These thinkers essentially suggest that the human mind evolved a dimmer switch mechanism. This is not an on-off switch, but rather a regulator (Jacobson, 2025). With too much awareness of death, the organism freezes, panics, or collapses. Too little, and life loses urgency, meaning, and care (Becker, 1973; Yalom, 2008).

So the psyche learned to keep mortality awareness just low enough to function and just high enough to motivate (Greenberg et al., 1986; Solomon et al., 2015).

That’s why so many people genuinely believe they don’t think about death or aren’t afraid of dying. They’re not lying. The system is working exactly as it’s supposed to (Greenberg et al., 1986; Pyszczynski et al., 2015). These defenses operate beneath conscious awareness, the same way breathing or balance does. You don’t feel yourself regulating your blood pressure either, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t happening.

In fact, one of the clearest signs that death anxiety is present is the firm belief that it isn’t (Solomon et al., 2015).

Becker’s insight was never that people walk around consciously terrified. It was that culture exists to make sure they don’t have to (Becker, 1973). Worldviews, identities, careers, religions, politics, moral certainty, and even the idea of being a “good person” quietly serve the same psychological function: they tell us we matter in a universe that otherwise wouldn’t notice our disappearance (Becker, 1973; Greenberg et al., 1986). Once those structures are in place, the fear drops out of awareness. The dimmer switch does its job (Jacobson, 2025).

This is also why these ideas often provoke irritation or dismissal instead of curiosity. When someone encounters them for the first time, they aren’t just learning new information. They’re brushing up against the scaffolding that holds their sense of reality together. The mind doesn’t experience that as insight. It experiences it as a threat (Greenberg et al., 1986; Pyszczynski et al., 2015). The response isn’t “Is this true?” so much as “Why does this feel wrong?”

Zapffe pushed this even further and suggested that consciousness itself may be over-equipped for the world it inhabits. We see too much, anticipate too far ahead, and know too well how the story ends (Zapffe, 1933/2010). The defenses he described—isolation, distraction, anchoring, and sublimation—aren’t moral failures. They’re survival strategies (Zapffe, 1933/2010). Without them, the weight of existence would be crushing. So when people recoil from these ideas, they’re doing exactly what the human animal evolved to do.

This is where my work sits.

Artists tend to live closer to that fault line. It's not because we're braver or more enlightened, but rather because creative practice weakens the dimmer switch (Jacobson, 2025; Rank, 1932). Making art requires attention, dwelling, repetition, and exposure. Over time, some of the automatic defenses erode. You keep looking where others glance away. That doesn’t make life easier. It makes it more honest.

This is why arts-based research matters so much to me (Barone & Eisner, 2012). I’m not trying to convince anyone with arguments alone. I’m showing what happens when someone lives with the dimmer turned slightly higher than average and then tries to metabolize what comes into view. The artifacts aren’t illustrations of theory. They are the evidence of a nervous system and a psyche working under different conditions.

So when someone says, “I don’t have death anxiety,” I hear, “My defenses are intact.” And when they say, “This feels abstract,” I hear, “This is getting too close to something I’ve spent my life not naming.”

That isn’t a failure of communication. It’s the terrain.

My work isn’t about forcing understanding. It’s about creating conditions where understanding can happen without overwhelming the person encountering it (Barone & Eisner, 2012; Jacobson, 2025). That’s why I move through story, image, material, land, and memory. I’m not avoiding theory. I’m respecting the psychology that makes theory hard to hear in the first place (Becker, 1973; Solomon et al., 2015).

And in that sense, the difficulty isn’t a flaw in these ideas.

It’s the sound the dimmer switch makes when you try to turn it up.

The resistance.

The discomfort.

The urge to look away.

Those aren’t misunderstandings.

They’re the evidence.

References

Barone, T., & Eisner, E. W. (2012). Arts-based research. SAGE.

Becker, E. (1973). The denial of death. Free Press.

Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., & Solomon, S. (1986). The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: A terror management theory. In R. F. Baumeister (Ed.), Public self and private self (pp. 189–212). Springer.

Jacobson, Q. (2025). Living with the dimmer switch [Blog post manuscript]. Unpublished.

Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., & Greenberg, J. (2015). Thirty years of terror management theory: From genesis to revelation. In J. M. Olson & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 52, pp. 1–70). Academic Press.

Rank, O. (1932). Art and artist: Creative urge and personality development. W. W. Norton.

Solomon, S., Greenberg, J., & Pyszczynski, T. (2015). The worm at the core: On the role of death in life. Random House.

Yalom, I. D. (2008). Staring at the sun: Overcoming the terror of death. Jossey-Bass.

Zapffe, P. W. (2010). The last messiah. (Original work published 1933)

A Salt Print From Another Life

I printed this 4x5 salt print today from a negative I made back in 2009, when I was living in Germany. Pulling an old plate like this into the present is always a strange experience. It’s like opening a time capsule you didn’t realize you buried. The negative was unvarnished—intentionally, because I wanted to see how far the elements had carried it over sixteen years. The result is this distressed, fractured surface that feels less like damage and more like memory asserting itself.

The subject is a simple setup: a cigar-box guitar propped on an old chair, a yarmulke (I got in Budapest) hanging beside it. At the time, I was thinking about the way ordinary objects can hold the weight of identity and belonging. Today, the print reads differently. The salt process softened everything, pulled it into an older register. The marks, flaws, and chemical bruises add a gravity the original plate didn’t have. It’s as if the print has aged along with me, and it’s finally showing its own scars.

Salt prints have a way of whispering rather than shouting. They blur the line (no pun) between what’s depicted and what’s remembered. This one carries the ghosts of two moments: who I was in 2009, exploring Europe with a camera and too many questions, and who I am now, printing in the desert, working at the intersection of creativity and mortality. These processes keep teaching me that nothing stays untouched—not glass plates, not bodies, not beliefs. Everything changes.

What I love most about this print is that it feels like a conversation between past and present versions of myself. A reminder that every piece of work we make continues living long after we think we’ve finished with it.

Impermanence and Insignificance: A Brief Note from the Void

I’ve been sitting with Escape from Evil again, and every time I revisit Becker’s later work, I feel the same jolt. He names the thing we spend our lives circling. Not death, exactly, but the quieter dread underneath it, the fear of slipping through this world without leaving so much as a fingerprint. Impermanence on one side. Insignificance on the other. It’s a tight little vise. And it’s psychologically terrifying.

Becker saw our terror clearly: we are symbolic creatures who can imagine infinity, yet we’re trapped in these fragile, temporary bodies that can vanish in a moment. The universe isn’t just big. It’s indifferent. And in that indifference, we feel an echo of our own smallness.

“The real fear isn’t the moment of dying. It’s the reckoning that follows: what does our ending reveal about how we lived?”

Most of us respond by building what Becker called “immortality projects”—the long list of things we hope will grant us some kind of permanence (like what I’m doing right now). Careers. Families. Beliefs. A reputation. A legacy. Art. Even the small rituals of daily life can start to feel like talismans against oblivion. Becker never mocked these efforts. He understood their necessity. Without them, we’d drown in the sheer scale of our vulnerability.

For me, that tension shows up every time I work. Photography, especially the old processes I use, makes this dance impossible to ignore. A wet collodion plate holds everything and nothing at once. Light settles on silver and forms an image that can last centuries, yet the plate itself is so delicate you can wipe it clean with a rag or crack it between two fingers. It’s the same paradox Becker lived in: durability wrapped in impermanence.

And honestly, that’s why I keep returning to these ancient materials. They tell the truth gently. They remind me that nothing I make will rescue me from the limits of being human. But the making still matters. Maybe that’s the part Becker understood so well: our projects don’t need to defeat insignificance; they only need to give us a way to live with it.

Impermanence isn’t the enemy. Insignificance isn’t a verdict. They’re conditions. The water we swim in, if you will.

What we create—our art, our relationships, our gestures of care—won’t make us immortal. But they mark our brief time here with intention rather than avoidance. They let us stand, for a moment, in the truth of our smallness and still say: I was here. I noticed. I tried.

That might be enough.

„Engel auf dem Käfertaler Friedhof“, 2009 – Gold toned salt print from a whole plate wet collodion negative.

Ruptureology and Rupturegenesis

Have you ever heard of those words? Probably not.

“Ruptureology” and “rupturegenesis” are words that I’ve created to use with my study of creativity and mortality.

Here are some of my notes on this topic as well as part of a self-directed study on the topic (all draft forms).

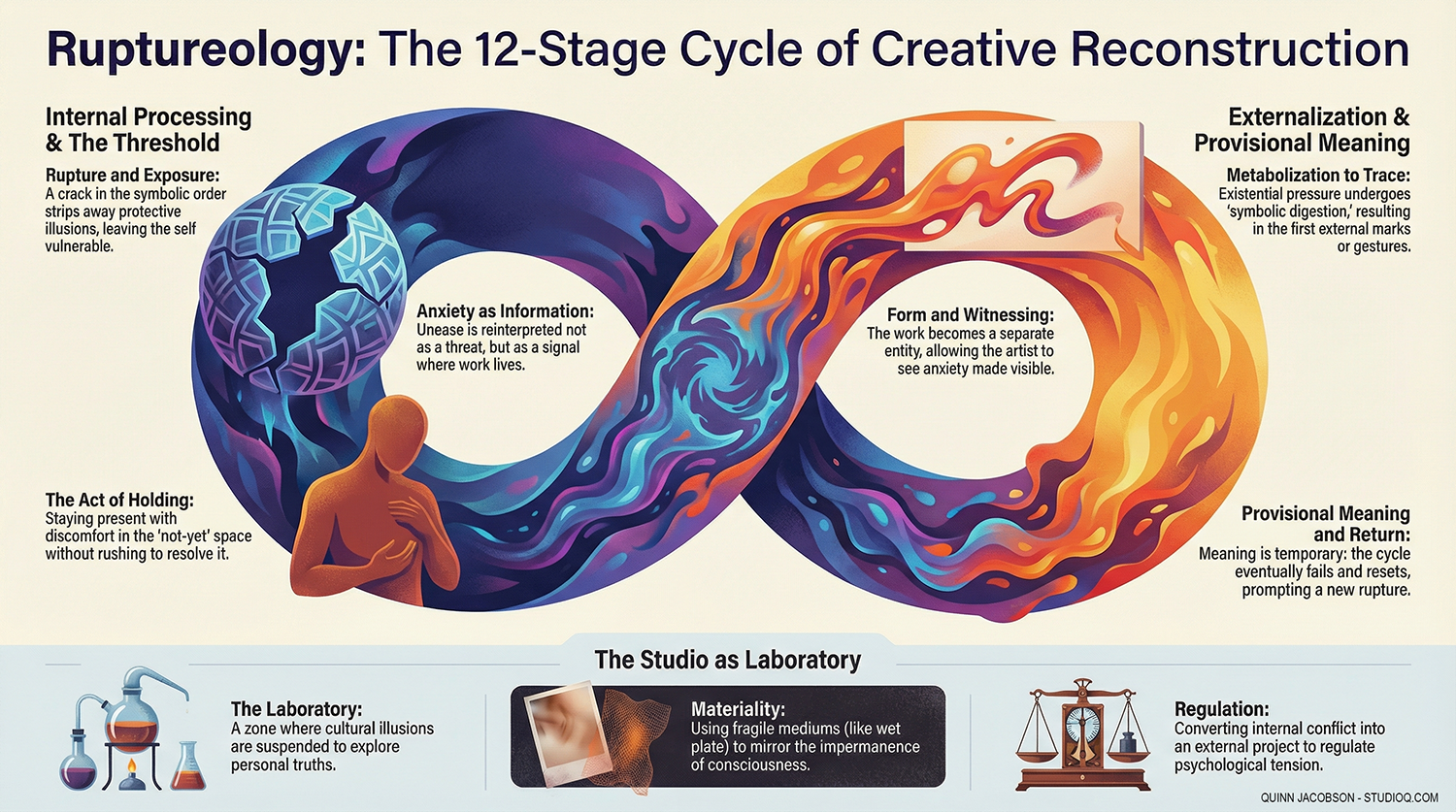

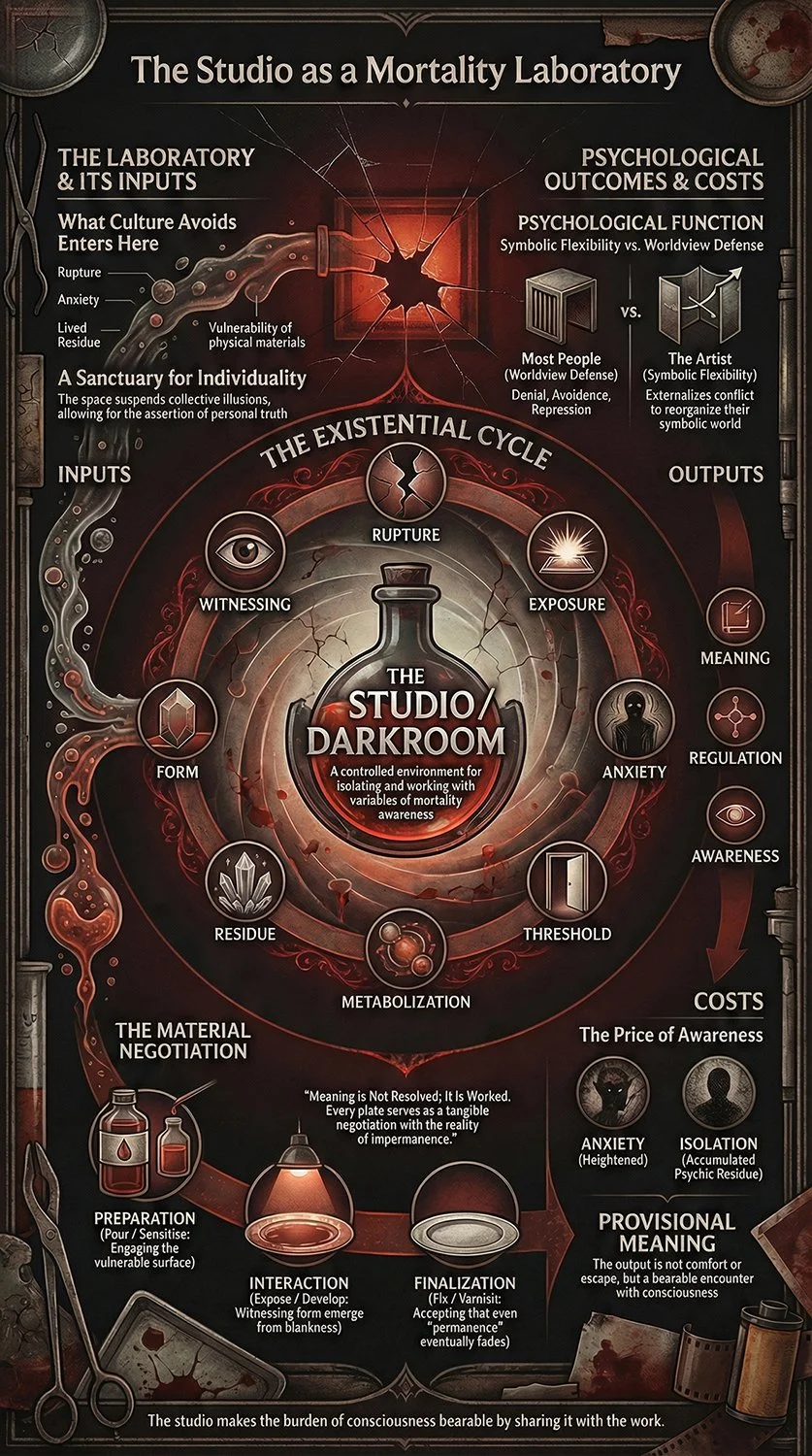

Ruptureology

The study and practice of living and creating through rupture.

Ruptureology examines what happens when existential defenses collapse—when illusions, cultural buffers, or inherited meanings no longer hold. It asks: how do we metabolize that collapse into form, meaning, and transformation?

In essence, ruptureology is both a psychology and a poetics of confrontation. It studies the processes—psychological, creative, and cultural—by which individuals and societies either deny or integrate death anxiety. The artist, for example, does not seek to repair rupture but to work within it, turning fragmentation into insight, and terror into trace.

“I don’t condemn the illusions people construct to buffer death anxiety. My interest is in what happens when those illusions collapse—whether creative practice can transform the raw terror of mortality into meaning, rather than violence or denial.” Jacobson, Response to Anxiety (n.d., p. 1)

Rupturegenesis

The generative aftermath of rupture—the birth that follows breakdown.

If ruptureology studies the terrain of collapse, rupturegenesis is the alchemical process by which something new emerges from it. It is the transmutation of existential dread into symbolic residue—art, insight, empathy, or ethical awareness.

Rupturegenesis is not redemption or transcendence; it is the slow, embodied making of meaning within finitude. It is how the artist metabolizes death anxiety into creative output—how “terror becomes trace.”

Alchemy

The symbolic process of transformation. In creative and psychological terms, alchemy is how matter—chemical, emotional, or symbolic—is transmuted into meaning. In the collodion process, silver becomes image through ritual and risk. In ruptureology, anxiety becomes insight through creation.

“The transformation of silver salts into an image isn’t just chemistry; it’s alchemy. That alchemical act becomes a metaphor for the way artists transmute existential terror into meaning.” — Jacobson, SDS Overview or Concept (2025, p. 1)

Collapse

The psychic and cultural moment when death anxiety breaches denial. Collapse reveals the fragility of our worldviews and the insufficiency of our myths. It is the point where symbolic immortality fails—and the raw void becomes visible.

But collapse can also mark the beginning of rupturegenesis: the opening through which new forms of meaning emerge. Artists dwell here—between fracture and formation.

Metabolize

The internal reworking of existential anxiety into creative or ethical form. To metabolize is to take in the unbearable and convert it into expression rather than repression. This word bridges Rank’s distinction between the artist and the neurotic: one chokes on the world, the other chews it into meaning.

“By transforming terror into form, the artist reworks rupture into creative output: an external trace, a witness to mortality.” Jacobson, SDS Overview or Concept (2025, p. 1)

Residue / Trace

The tangible and symbolic remainder of an encounter with mortality. Residue is the mark left behind—the plate, the scar, the sentence, the memory. It is both evidence and echo, proof that meaning once passed through matter. I’ve said these words for years. The art happens in the making. The plate itself is residue; it captures the essence of the moment, the shadow of the sitter (or still life), and the fragility of life.

Witness

The conscious act of seeing and staying with what culture denies. Witnessing is both artistic and ethical; it resists erasure by turning the gaze toward suffering, mortality, and historical trauma. In my practice, witness is not documentation—it’s participation. To witness is to stand in relation to the void and refuse to look away.

Immanence

Meaning found within finitude. Immanence rejects transcendence or escape; it roots significance in the here and now. In ruptureology, immanence is the field in which all transformation occurs—the realization that nothing lies beyond death and that creation itself is the sacred act.

Collapse → Rupture → Metabolize → Trace → Witness → Immanence → Rupturegenesis

This is my through line of rupture—a living process of descent and creation. It maps the cycle through which anxiety becomes art, illusion gives way to insight, and denial is replaced by presence.

Otto Rank’s Personality Types

Rank’s Three Personality Types

Adapted (the “normal” person): Finds security in culture, tradition, religion, consumerism, or ideology. Adapted individuals manage their fear of death by adhering to social norms. Creativity, if expressed, stays within socially approved channels.

Neurotic: Overwhelmed by existential fear. The individual withdraws inward, unable to sublimate their anxiety. “Chokes” on mortality awareness, unable to transform it into external work.

Creative / Artist: Equally exposed to death anxiety, but metabolizes it through art or thought. Reworks inner terror into external form (art, philosophy, writing). They exist in a state of tension with culture, frequently stepping outside its protective illusions.

This framework clarifies that the "normal/adapted" person is not absent; rather, they represent the cultural baseline.

Rank’s Types Through the Lens of Ruptureology (my conversion)

Adapted (Buffered): Aligns with the dominant worldview to avoid rupture. The individual utilizes cultural shields such as religion, nationalism, and consumerism to suppress their awareness of death. Lives are “protected” inside the illusion—death anxiety is smoothed over rather than faced.

Neurotic (Collapsed): The rupture breaks through without mediation. The individual feels overwhelmed by mortality and struggles to transform it into meaning. Anxiety implodes inward, leading to paralysis or dysfunction.

Creative / Artist (Metabolizing Rupture): Confronts the rupture rather than fully denying or collapsing under it. Death anxiety becomes raw material—transformed into art, philosophy, ritual, or resistance. Lives on the edge between denial and confrontation, where meaning is forged.

This dovetails with my Through Line of Rupture:

Buffer → Collapse → Metabolize

The adapted “normal” person lives buffered.

The neurotic collapses under rupture.

The artist metabolizes rupture into creation.

Proximal and distal terror management defenses

Rank (1932/1989) distinguished between the adapted person, the neurotic, and the artist in relation to how each responds to existential anxiety:

“The average man avoids the worst effects of the fear of life and of death by complete adaptation to the collective. He lives not in himself, but in society; he seeks not his own immortality, but to participate in the immortality of the group” (p. 34).

“The neurotic suffers from the same increased consciousness of self as the artist, but he cannot objectify and render it harmless in creative work. He chokes on his own introversions” (pp. 55–56).

“The artist lives the double conflict of the individual and the collective more consciously than others, but he overcomes it in the work of art which creates a new unity of his personality with nature and with humanity. … The artist is able to overcome introversion by projecting his fears into the work of art, where they are mastered, objectified, and given form” (pp. 58, 70).

References:

Jacobson, Q. (n.d.). Response to anxiety [Unpublished manuscript].

Jacobson, Q. (2025, October 3). SDS overview or concept [Unpublished manuscript].

Rank, O. (1989). Art and artist: Creative urge and personality development (C. F. Atkinson, Trans.). W. W. Norton. (Original work published 1932)