Introduction

In the Shadow of Sun Mountain (2020–2024)

I lived for years on twelve acres in the mountains of central Colorado, on land where the (Tabeguache) Ute had lived, traveled, gathered medicine, and buried their dead for thousands of years. That fact was not abstract to me. It was present every day. In the plants that grew around the house. In the way the light moved across the ground. In the silence that settled at dusk. The land didn’t feel empty. It felt inhabited by memory.

Sun Mountain rose nearby, not dramatically, not as a monument, but as a constant presence. Its shadow crossed the land in long, slow arcs. I began to understand that shadow less as an absence than as a reminder. Something persisted there, something unresolved. The land wasn’t haunted in the theatrical sense. It was honest. It held the residue of belief, fear, violence, endurance, and the stories that try to make those things bearable.

The plants themselves became teachers. This work is grounded in ethnobotany and spiritual ecology, not as metaphor, but as epistemology. The (Tabeguache) Ute understood land through use, relationship, and attention: which plants heal, which harm, which alter perception, which open ritual space, which return the body to the ground. Medicine was not separate from cosmology. Knowledge was embedded in practice, repetition, and care. Working among these plants, photographing them, painting them, and incorporating them into mixed media was a way of entering that lineage of attention, however imperfectly. The work does not claim that knowledge as mine, but it does acknowledge that plants carry memory and instruction, and that ways of knowing grounded in land and body predate and quietly challenge the abstractions that made conquest and erasure possible.

This work began with a question I couldn’t shake: why do human beings need an enemy to feel secure?

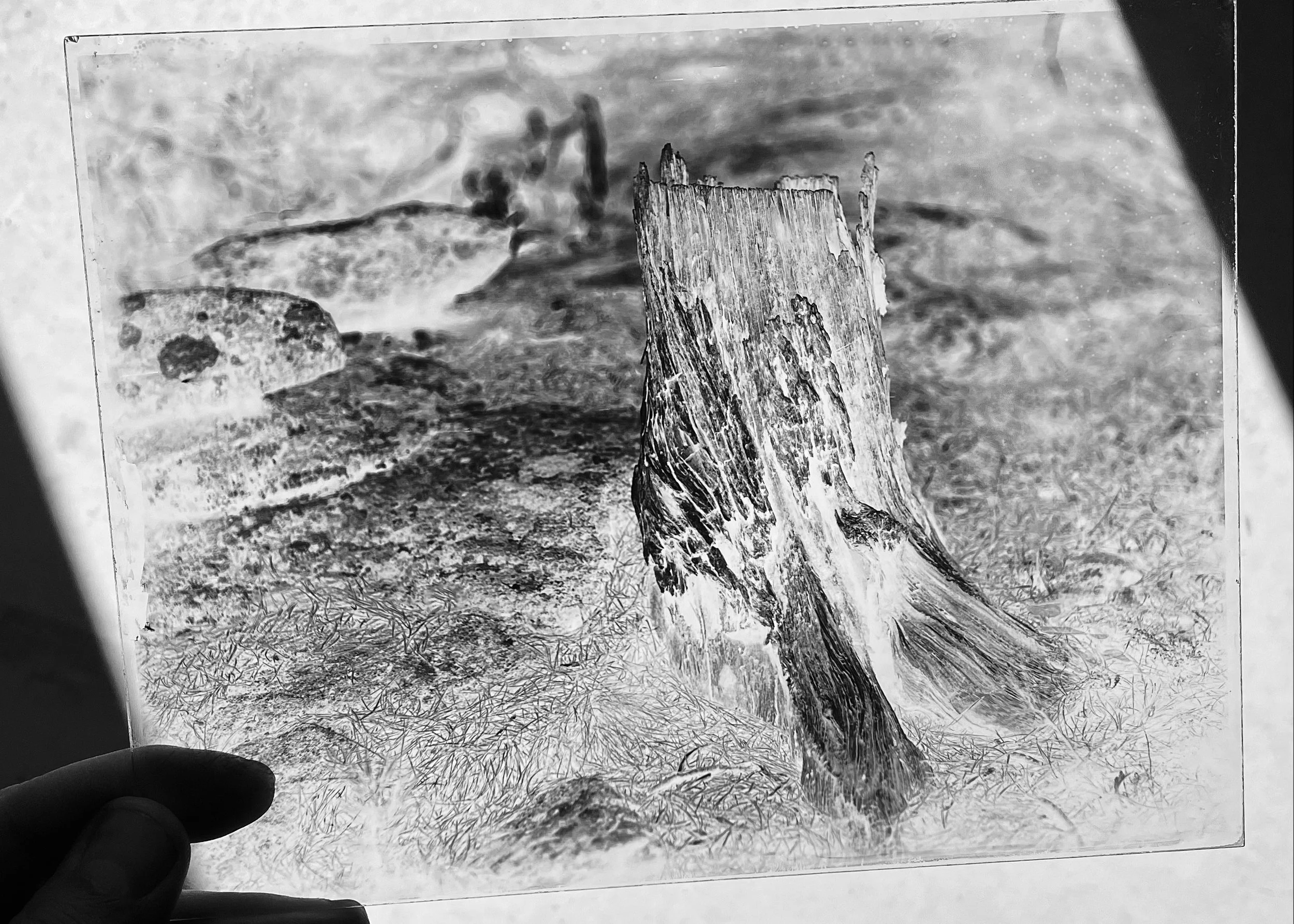

The Great Mullein Plant—Palladiotype from a wet collodion negative. 2022

I’d spent years photographing sites where violence had taken place, standing in spaces where something irreparable had occurred and sensing that the story told about those events was never the whole story. Living on that land intensified the question. The history of the (Tabeguache) Ute was not distant. It was botanical. Ecological. Embedded in place. Their knowledge of medicinal plants, spiritual botany, seasonal movement, and relationship to land was not a footnote to history. It was a worldview that had been violently interrupted.

The longer I lived there, the clearer it became that the question wasn’t only historical. It was psychological. What allows people to draw a line between “us” and “them” with such confidence? Why does that line harden so quickly? And what does our buried awareness of being temporary have to do with it?

My studio practice kept circling the same terrain. I worked with wet-collodion photography, color reversal prints, painting, and mixed media not out of nostalgia, but because these materials resist control. Collodion is unstable. A glass plate can appear solid and fail without warning. Silver remembers everything. Chemistry responds to temperature, breath, humidity, and time. You don’t dominate the process; you negotiate with it.

That instability mattered. It mirrored something I recognized in the human mind when it tries to manage fear, especially fear it refuses to name. What began as an old photographic process became a form of inquiry. The fractures in the plates, the fogging, the lifting emulsion, the breakage, they echoed the fractures I was seeing in our collective imagination.

Ernest Becker helped sharpen that connection. He argued that culture itself is a defense system built around the fact that we will die (Becker, 1973). We build worldviews to seem steady. We cling to identity because it promises continuity. And when those stories feel threatened, we look outward for someone to blame.

Othering is not an accident. It’s a psychological survival strategy. A way to redirect fear so we don’t have to feel it directly.

In the Shadow of Sun Mountain grew from that realization. What began as an artistic investigation rooted in land, plants, and material practice expanded into a broader inquiry into how death anxiety shapes behavior, morality, and the human capacity for cruelty. Starting a PhD in my sixties didn’t create this path. It helped me name it. Becker, Rank, and the existentialists gave language to what I had been sensing intuitively for decades: that creativity is not separate from mortality, and that artists often work at the fault line where denial begins to crack.

The chapters that follow trace how fear becomes ideology. How ideology becomes violence. How violence becomes history. And how history becomes a story we repeat so we don’t have to confront what made the violence possible in the first place.

This isn’t a moral lesson. It isn’t a condemnation delivered from a safe distance. It’s an examination of the ordinary human mind and what it does with the knowledge that life is short, unpredictable, and finite. It’s about the psychological architecture we inherit, the beliefs we defend, and the places where those beliefs fail.

Sun Mountain is both literal ground and conceptual ground. The plants, the landscapes, the objects, the materials, and the photographic processes are not illustrations of theory. They are part of the thinking itself. The shadow it casts represents what we push away: the parts of ourselves we disown, project, or punish in others.

If there is any hope here, it’s a quiet one. That facing impermanence might soften the need to harden ourselves against difference. Artists understand that tension intimately. We work every day between creation and loss. We accept what breaks. We learn from what cannot be repaired.

This book is an invitation into that space. It begins with a question and refuses to resolve it too quickly. It follows it through land, material, history, psychology, and lived experience, toward a clearer understanding of what we do in the presence of death, and what might change if we learned to see ourselves more honestly.

References

Becker, E. (1973). The denial of death. Free Press.