One of the biggest challenges I face when I talk about Becker, Rank, Zapffe, or Terror Management Theory isn’t that the ideas are too complex. It’s that they’re describing the very psychological machinery that makes them difficult to understand in the first place. (Becker, 1973; Greenberg et al., 1986; Rank, 1932; Zapffe, 1933/2010).

That’s the paradox.

From an evolutionary perspective, human consciousness didn’t just give us language, imagination, and culture. It gave us a problem no other animal has to solve: we know we’re going to die, and we know it with enough clarity to make life unbearable if that awareness stayed fully online all the time (Becker, 1973; Solomon et al., 2015). So evolution didn’t eliminate the problem. It built a workaround.

These thinkers essentially suggest that the human mind evolved a dimmer switch mechanism. This is not an on-off switch, but rather a regulator (Jacobson, 2025). With too much awareness of death, the organism freezes, panics, or collapses. Too little, and life loses urgency, meaning, and care (Becker, 1973; Yalom, 2008).

So the psyche learned to keep mortality awareness just low enough to function and just high enough to motivate (Greenberg et al., 1986; Solomon et al., 2015).

That’s why so many people genuinely believe they don’t think about death or aren’t afraid of dying. They’re not lying. The system is working exactly as it’s supposed to (Greenberg et al., 1986; Pyszczynski et al., 2015). These defenses operate beneath conscious awareness, the same way breathing or balance does. You don’t feel yourself regulating your blood pressure either, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t happening.

In fact, one of the clearest signs that death anxiety is present is the firm belief that it isn’t (Solomon et al., 2015).

Becker’s insight was never that people walk around consciously terrified. It was that culture exists to make sure they don’t have to (Becker, 1973). Worldviews, identities, careers, religions, politics, moral certainty, and even the idea of being a “good person” quietly serve the same psychological function: they tell us we matter in a universe that otherwise wouldn’t notice our disappearance (Becker, 1973; Greenberg et al., 1986). Once those structures are in place, the fear drops out of awareness. The dimmer switch does its job (Jacobson, 2025).

This is also why these ideas often provoke irritation or dismissal instead of curiosity. When someone encounters them for the first time, they aren’t just learning new information. They’re brushing up against the scaffolding that holds their sense of reality together. The mind doesn’t experience that as insight. It experiences it as a threat (Greenberg et al., 1986; Pyszczynski et al., 2015). The response isn’t “Is this true?” so much as “Why does this feel wrong?”

Zapffe pushed this even further and suggested that consciousness itself may be over-equipped for the world it inhabits. We see too much, anticipate too far ahead, and know too well how the story ends (Zapffe, 1933/2010). The defenses he described—isolation, distraction, anchoring, and sublimation—aren’t moral failures. They’re survival strategies (Zapffe, 1933/2010). Without them, the weight of existence would be crushing. So when people recoil from these ideas, they’re doing exactly what the human animal evolved to do.

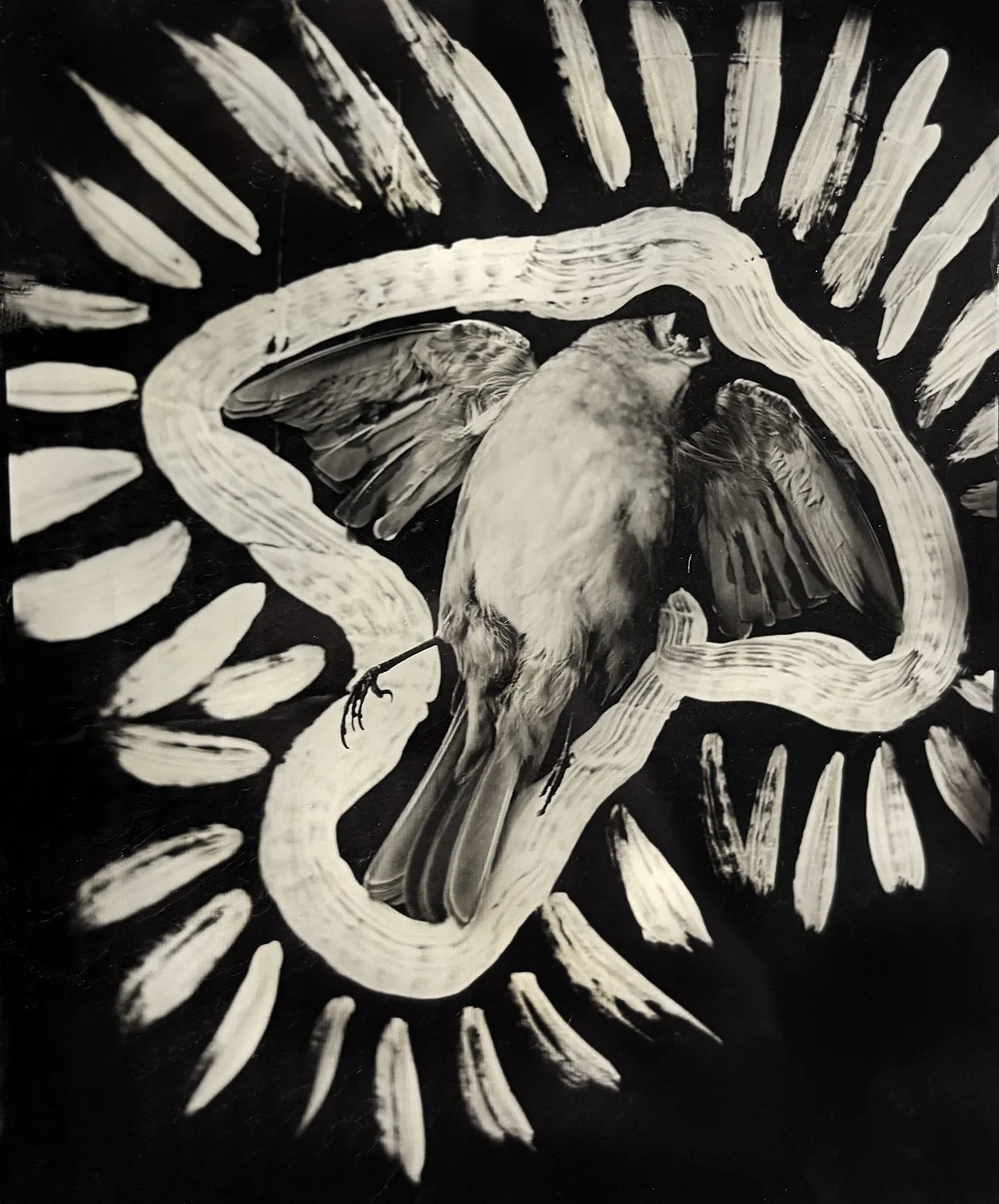

This is where my work sits.

Artists tend to live closer to that fault line. It's not because we're braver or more enlightened, but rather because creative practice weakens the dimmer switch (Jacobson, 2025; Rank, 1932). Making art requires attention, dwelling, repetition, and exposure. Over time, some of the automatic defenses erode. You keep looking where others glance away. That doesn’t make life easier. It makes it more honest.

This is why arts-based research matters so much to me (Barone & Eisner, 2012). I’m not trying to convince anyone with arguments alone. I’m showing what happens when someone lives with the dimmer turned slightly higher than average and then tries to metabolize what comes into view. The artifacts aren’t illustrations of theory. They are the evidence of a nervous system and a psyche working under different conditions.

So when someone says, “I don’t have death anxiety,” I hear, “My defenses are intact.” And when they say, “This feels abstract,” I hear, “This is getting too close to something I’ve spent my life not naming.”

That isn’t a failure of communication. It’s the terrain.

My work isn’t about forcing understanding. It’s about creating conditions where understanding can happen without overwhelming the person encountering it (Barone & Eisner, 2012; Jacobson, 2025). That’s why I move through story, image, material, land, and memory. I’m not avoiding theory. I’m respecting the psychology that makes theory hard to hear in the first place (Becker, 1973; Solomon et al., 2015).

And in that sense, the difficulty isn’t a flaw in these ideas.

It’s the sound the dimmer switch makes when you try to turn it up.

The resistance.

The discomfort.

The urge to look away.

Those aren’t misunderstandings.

They’re the evidence.