Glasshead–Stoneman (Animality Study)—half-plate wet collodion negative. January 18, 2026

A stone-assembled figure crowned with a fractured glass head stands before blurred skulls, holding the tension between human symbolic striving and our inescapable animal condition.

Animality: The Part of Us We Keep Trying to Forget

One of the simplest but hardest ideas for people to accept is that we are animals who know we will die.

That sentence alone has more psychological weight than most of us want to deal with. We are more than just living things that move through time. We are aware of ourselves, and our bodies get older, break down, and disappear. And we know this. That information alters everything.

This is where Ernest Becker begins. In The Denial of Death, Becker posited that human psychology is influenced by a fundamental contradiction. We are biological entities motivated by instinct, hunger, fear, and reproduction; concurrently, we are symbolic entities endowed with imagination, language, and self-reflection. We have bodies that will die, and our minds can picture that death before it happens. The conflict between those two facts never goes away. It just gets taken care of.

That tension is right in the middle of animality.

Being an animal means being weak. People bleed. Bodies decay. Bodies break down. That doesn't change, no matter how smart or culturally accomplished you are. But most of modern life is set up to keep that truth far away. We keep the dying out of sight. We make decay into a medical issue. We raise the mind, the self, the brand, and the legacy as if they could somehow float away from the body.

Terror Management Theory says that this is not a coincidence. When reminders of our animal nature break through, like illness, aging, death, or even some kinds of art, they make us anxious on a deep, often unconscious level. The answer is almost never calm, though. It's protection. We hold on to our identities, beliefs, status, and moral frameworks more tightly when they promise that we are more than just meat that is going to die out.

The skull has always been one of the best ways to show this problem. It takes away everything that makes us who we are, reminding us that we are just physical matter with a time limit. Skulls don't fight. They don't talk about it. They just give testimony.

Rachel and Ross Menzies talk about how much of human behavior is based on avoiding this confrontation in their book Mortals. Not just being afraid of dying, but being afraid of being an animal that has to die. We deal with that fear by keeping busy, doing health rituals, telling success stories, and always trying to be better. In most cases, the goal is not to live forever. It is a mental distance from what will happen to the body.

That's what this picture is trying to show.

The Glasshead–Stoneman is standing up, put together, and almost ceremonial. The stone blocks make up a body that looks solid, scarred, planned, and calm. The glass head on top is clear, glowing, broken, and fragile. Skulls float behind it, not quite there and not quite gone. They didn't read as reminders of death, but as witnesses. The truth about animals is there, but it won't stay out of the way.

Glass is important here. Heat and violence make glass. It looks like it will last forever, but it breaks easily. It shows its own cracks while carrying light. It is an uncomfortable material that is between solid and broken. A lot like the human self.

Stone suggests strength. Glass makes things look fragile. The skulls show that something is going to happen.

They make a quiet argument that no amount of structure or symbolic architecture can change our animal nature. We can make identities. We can add meaning. We can give ourselves names. But the body is still there. The animal is still there. Death stays.

Even though it makes people uncomfortable, this is not a negative statement. Becker himself thought that this tension is what makes creativity, art, and meaning come to life. The issue does not stem from our animalistic nature. The issue is that we put so much effort into pretending we aren't.

Art does something important for the mind when it lets animality back into the room without being showy or moralizing. It lowers the defenses just enough for the person to be recognized. Don't panic. Acknowledgment. The kind that says, "This is what we have to work with."

The Glasshead–Stoneman does not fix the problem. It doesn't make you feel better. It just keeps the animal and the symbol in the same frame, not letting either one go away.

That might be enough.

Because confronting our animality does not diminish the significance of life. It makes it sharper. It reminds us that everything we build, love, and make is done inside a body that will eventually fail. And oddly enough, that's what makes those actions important.

Untitled (Red Hand)

Acrylic mixed media on paper, 4.25" × 5.5"

A red hand interrupts three attenuated figures, marking the moment where existential anxiety is no longer diffuse but made contact—contained, metabolized, and rendered visible through form.

The Red Hand Problem

How artists metabolize existential anxiety, and why the work still matters.

I keep returning to the same question, no matter how many theories I read or objects I make: What exactly happens to existential anxiety when it moves through the hands of an artist?

Not rhetorically. Mechanically. Psychologically.

The image above is one attempt to make that process visible. Three pale figures stand upright, stripped of detail, reduced almost to afterimages. They are not portraits so much as placeholders. Awareness has rendered their bodies thin. Over them reaches a red hand, oversized and intrusive, neither comforting nor gentle. It interrupts and intrudes. It stains. It marks.

That hand is not expression. It is intervention.

Most people manage death anxiety by keeping it diffuse, by never letting it fully localize. The artist does the opposite. The anxiety is brought forward, concentrated, and given a task. Creation becomes a site of containment. The fear does not disappear, but it changes state. It becomes workable.

This is what I mean by metabolizing existential anxiety. Not purging it. Not transcending it. Converting it into form.

Psychologically, this matters more than we often admit. The act of making gives the anxious mind boundaries. Time slows. Attention narrows. The self becomes less abstract and more procedural. The question shifts from What does it all mean? to What happens if I put this here? That shift is not trivial. It is regulatory. It allows consciousness to stay in contact with mortality without flooding.

The white figures in the image are not victims. They are witnesses. They stand because the hand is doing something on their behalf.

This is where arts-based research comes into focus for me. ABR is often framed as alternative knowledge production, which is true but incomplete. Its deeper value lies in its psychological function. Making becomes a way of thinking that does not rely exclusively on symbolic abstraction. Image, material, gesture, and repetition—these are not illustrations of insight; they are the insight.

When anxiety stays purely cognitive, it spirals. When it enters the body through making, it circulates. It acquires rhythm. It becomes legible.

This brings me to the harder question: is there any value in writing books like Glass Bones and Rupture?

If the goal were resolution, probably not. No book resolves the fact of death. No theory seals the crack. But that has never been the real task. The value lies in creating sustained containers where anxiety can be held long enough to be examined without collapsing into distraction or denial.

These books are not answers. They are pressure vessels.

Writing them will force me to stay with the material—psychologically and ethically—longer than images alone sometimes allow. It slows the metabolism. It traces the process. It makes visible what is usually hidden: how fear becomes form, how rupture becomes method, and how meaning is provisional but still worth making.

The red hand, then, is also authorship. It is the decision to intervene rather than look away. To touch the thing that makes us uncomfortable and accept the consequences of contact.

Artists do not escape existential anxiety (not at all). They work it. They give it edges. They give it weight. They give it somewhere to go.

That’s not a cure.

But it is a practice.

And in a culture built on denial, practice may be the most honest form of value we have left.

Leaving a trace—the mark of a white-winged dove on my kitchen window. December 28, 2025

A white-winged dove hits the glass, and what’s left behind isn’t the bird but the residue of contact: a powdery bloom, two wing smears, and a ghosted body shape suspended in light. That’s the interview in miniature. Dr. Fisher and I are circling the same problem from different angles: how the most real forces in a human life rarely show up directly. They show up as traces. As misreadings. As displaced language. As the “dimmer switch” doing its job.

I’m interested in what the awareness of an ending does to the living, minute by minute. The dove doesn’t leave a story; it leaves evidence. A mark that asks to be interpreted. It’s rupture without a sermon: meaning fails for a second, the world stutters, and then you’re standing there in your own kitchen looking at a fragile imprint and feeling the entire question come back online.

Interview With Dr. R. Michael Fisher: Careers of Folly and Wisdom

In this conversation, I sit down with Dr. R. Michael Fisher for Careers of Folly and Wisdom (Episode 3) at the close of 2025, and we trace the strange overlap between two lives shaped by study, teaching, and the long arc of existential pressure. What begins as a simple introduction quickly becomes a deeper exchange about why some ideas take decades to name and why the hardest work is often learning how to speak those ideas in public without having them reduced to something smaller.

We talk about how we connected through Southwestern College’s Visionary Practice & Regenerative Leadership doctoral program and why I went searching for faculty whose work could actually hold what I’m building: an arts-based inquiry into creativity, mortality, and the psychological machinery of denial. I share my early “folly” at residency, where I became “the death guy” despite my real focus being the opposite: what happens inside the dash between birth and death, and how the knowledge of impermanence reshapes a human life. That misreading became a kind of field experiment in real time, revealing how quickly people reroute mortality talk into safer channels like grief, loss, or therapeutic language. It also forced me to sharpen my communication, not by diluting the thesis, but by learning how to meet the audience where the “dimmer switch” is already working.

From there, the conversation widens. Dr. Fisher pushes on the themes of education, fallibility, and maturity: how a person with deep content and lived experience learns to teach without preaching, and how humility becomes an actual method. I bring in two foundational touchstones that anchor my work: Becker’s insistence that death terror is a mainspring of human activity and Rank’s claim (via Becker) that the artist takes in the world and reworks it rather than being crushed by it. That tension is the engine of my research question: if most of culture is organized to keep death out of view, what do artists do differently with that same pressure, consciously or unconsciously?

A major thread running through the interview is that denial is not just a personal quirk. It’s cultural, political, and historical. I talk about early experiences that formed my worldview, including family stories that complicate simple narratives of “normal” American life, and how those early exposures shaped my sensitivity to power, erasure, and the stories nations tell themselves. We also move into my military background, where I describe the kind of learning you don’t go looking for: the collision between youthful exceptionalism and the realities of violence, trauma, and institutional harm, including witnessing suicide deaths while working as a photographer. The folly, as I name it, is the arrogance of certainty; the wisdom is the painful clarity that comes after the myth breaks.

In the final stretch, we pivot to Dr. Fisher’s work in fearology and his reframing of Terror Management Theory as, in many ways, a kind of “fear management education.” That exchange matters because it shows the real stakes of language: fear, terror, anxiety, and denial. These aren’t interchangeable terms, and both of us have been forced to grapple with how quickly audiences collapse complex ideas into familiar clichés. We end with a concise statement of my own working thesis, offered almost like a poem: artists tend to give anxiety form rather than discharge it through denial; material practice slows experience enough for mortality to move into objects; rupture is where meaning fails, and art often happens there; the ethic is not to “fix” the break, but to stay present with it.

The conversation closes on an honest note about the cost of passion. We talk about parenting, devotion to work, and the ways even meaningful lives leave blind spots in their wake. If this episode has a through-line, it’s that wisdom is rarely clean. It comes out of misfires, misreadings, and the slow work of learning how to hold the real without turning it into a brand, a sermon, or a therapy session.

I really enjoyed the conversation, and I look forward to working with Dr. Fisher. Check out his YouTube channel and his other interviews and commentary.

Punished for Embodiment. Half-plate tintype (4.25 × 5.5 in.). December 2025.

Western art has long tried to discipline the body—shrinking it, idealizing it, and denying its animality. This work pushes back. The figure is restrained not for what he has done, but for what he is: a vulnerable organism aware of its own end. The skull waits behind him, already finished with the struggle.

Living With The Dimmer Switch

One of the biggest challenges I face when I talk about Becker, Rank, Zapffe, or Terror Management Theory isn’t that the ideas are too complex. It’s that they’re describing the very psychological machinery that makes them difficult to understand in the first place. (Becker, 1973; Greenberg et al., 1986; Rank, 1932; Zapffe, 1933/2010).

That’s the paradox.

From an evolutionary perspective, human consciousness didn’t just give us language, imagination, and culture. It gave us a problem no other animal has to solve: we know we’re going to die, and we know it with enough clarity to make life unbearable if that awareness stayed fully online all the time (Becker, 1973; Solomon et al., 2015). So evolution didn’t eliminate the problem. It built a workaround.

These thinkers essentially suggest that the human mind evolved a dimmer switch mechanism. This is not an on-off switch, but rather a regulator (Jacobson, 2025). With too much awareness of death, the organism freezes, panics, or collapses. Too little, and life loses urgency, meaning, and care (Becker, 1973; Yalom, 2008).

So the psyche learned to keep mortality awareness just low enough to function and just high enough to motivate (Greenberg et al., 1986; Solomon et al., 2015).

That’s why so many people genuinely believe they don’t think about death or aren’t afraid of dying. They’re not lying. The system is working exactly as it’s supposed to (Greenberg et al., 1986; Pyszczynski et al., 2015). These defenses operate beneath conscious awareness, the same way breathing or balance does. You don’t feel yourself regulating your blood pressure either, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t happening.

In fact, one of the clearest signs that death anxiety is present is the firm belief that it isn’t (Solomon et al., 2015).

Becker’s insight was never that people walk around consciously terrified. It was that culture exists to make sure they don’t have to (Becker, 1973). Worldviews, identities, careers, religions, politics, moral certainty, and even the idea of being a “good person” quietly serve the same psychological function: they tell us we matter in a universe that otherwise wouldn’t notice our disappearance (Becker, 1973; Greenberg et al., 1986). Once those structures are in place, the fear drops out of awareness. The dimmer switch does its job (Jacobson, 2025).

This is also why these ideas often provoke irritation or dismissal instead of curiosity. When someone encounters them for the first time, they aren’t just learning new information. They’re brushing up against the scaffolding that holds their sense of reality together. The mind doesn’t experience that as insight. It experiences it as a threat (Greenberg et al., 1986; Pyszczynski et al., 2015). The response isn’t “Is this true?” so much as “Why does this feel wrong?”

Zapffe pushed this even further and suggested that consciousness itself may be over-equipped for the world it inhabits. We see too much, anticipate too far ahead, and know too well how the story ends (Zapffe, 1933/2010). The defenses he described—isolation, distraction, anchoring, and sublimation—aren’t moral failures. They’re survival strategies (Zapffe, 1933/2010). Without them, the weight of existence would be crushing. So when people recoil from these ideas, they’re doing exactly what the human animal evolved to do.

This is where my work sits.

Artists tend to live closer to that fault line. It's not because we're braver or more enlightened, but rather because creative practice weakens the dimmer switch (Jacobson, 2025; Rank, 1932). Making art requires attention, dwelling, repetition, and exposure. Over time, some of the automatic defenses erode. You keep looking where others glance away. That doesn’t make life easier. It makes it more honest.

This is why arts-based research matters so much to me (Barone & Eisner, 2012). I’m not trying to convince anyone with arguments alone. I’m showing what happens when someone lives with the dimmer turned slightly higher than average and then tries to metabolize what comes into view. The artifacts aren’t illustrations of theory. They are the evidence of a nervous system and a psyche working under different conditions.

So when someone says, “I don’t have death anxiety,” I hear, “My defenses are intact.” And when they say, “This feels abstract,” I hear, “This is getting too close to something I’ve spent my life not naming.”

That isn’t a failure of communication. It’s the terrain.

My work isn’t about forcing understanding. It’s about creating conditions where understanding can happen without overwhelming the person encountering it (Barone & Eisner, 2012; Jacobson, 2025). That’s why I move through story, image, material, land, and memory. I’m not avoiding theory. I’m respecting the psychology that makes theory hard to hear in the first place (Becker, 1973; Solomon et al., 2015).

And in that sense, the difficulty isn’t a flaw in these ideas.

It’s the sound the dimmer switch makes when you try to turn it up.

The resistance.

The discomfort.

The urge to look away.

Those aren’t misunderstandings.

They’re the evidence.

References

Barone, T., & Eisner, E. W. (2012). Arts-based research. SAGE.

Becker, E. (1973). The denial of death. Free Press.

Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., & Solomon, S. (1986). The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: A terror management theory. In R. F. Baumeister (Ed.), Public self and private self (pp. 189–212). Springer.

Jacobson, Q. (2025). Living with the dimmer switch [Blog post manuscript]. Unpublished.

Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., & Greenberg, J. (2015). Thirty years of terror management theory: From genesis to revelation. In J. M. Olson & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 52, pp. 1–70). Academic Press.

Rank, O. (1932). Art and artist: Creative urge and personality development. W. W. Norton.

Solomon, S., Greenberg, J., & Pyszczynski, T. (2015). The worm at the core: On the role of death in life. Random House.

Yalom, I. D. (2008). Staring at the sun: Overcoming the terror of death. Jossey-Bass.

Zapffe, P. W. (2010). The last messiah. (Original work published 1933)

“Choking on Rocks,” Whole Plate (6.5” x 8.5”) wet collodion negative. October 2025.

Where My Work Is Heading

On Rewriting, Rebuilding, and Turning Toward Mortality

For years now, I’ve been circling the same set of questions, questions that live somewhere between psychology, philosophy, the studio, and the darkroom. Why do humans deny death? What holds our meaning structures together? And why do artists seem to approach these tensions differently than everyone else, often with a kind of clarity that only comes from standing close to fear?

I’ve been asked why In the Shadow of Sun Mountain still isn’t published. The simple truth is that the book outgrew its original frame. I wrote it during a period when I was wrestling with ideas that didn’t yet have the right container. What I couldn’t see then, but can see now, is that the book was waiting for the structure of my doctoral work. It needed a broader foundation, and I needed more time to understand what I was actually trying to say.

So instead of releasing it in its earlier form, I’ve decided to rework it as part of my PhD. It will become the third manuscript in a three-part sequence I’m developing during the program.

The first manuscript will be an explanation of these theories—death anxiety, denial, worldview defense, and the evolutionary roots of awareness—in a way anyone can read and understand. Simple, accessible, and grounded. The working title is Glass Bones.

The second manuscript will be directed toward artists and toward creatives and will explore how they metabolize existential concerns in ways that differ from non-artists. It will look closely at creative practice as a pathway for meaning-making. The working title is Rupture.

And the third will be a rewritten In the Shadow of Sun Mountain, offered as a real-life example of an artist metabolizing these ideas through creative work, reflection, and lived experience.

All of this leads to the question that my dissertation will take up directly:

What actually happens inside an artist when they confront mortality in their creative practice?

To answer that, I’m turning toward arts-based research methodology. ABR is a natural fit for the work I’ve been doing for decades, because in ABR, the studio becomes the site of inquiry. The process becomes a way of knowing. Material becomes a kind of data. Instead of illustrating findings after the fact, the creative act generates them. It’s not about making art that explains theory; it’s about letting the art reveal what theory can’t access on its own.

So the dissertation will center on creating a completely new body of artwork, work made specifically for this research. Clay figures and/or objects suspended or collapsing under their own weight. Wet collodion images that feel like memory rising through fog and confusion. Paintings and photographs that follow the direction of the inquiry. I want the research to grow out of the process itself, out of the contact with clay, with silver, with pigment, with symbol, and with the ambiguous space where meaning forms.

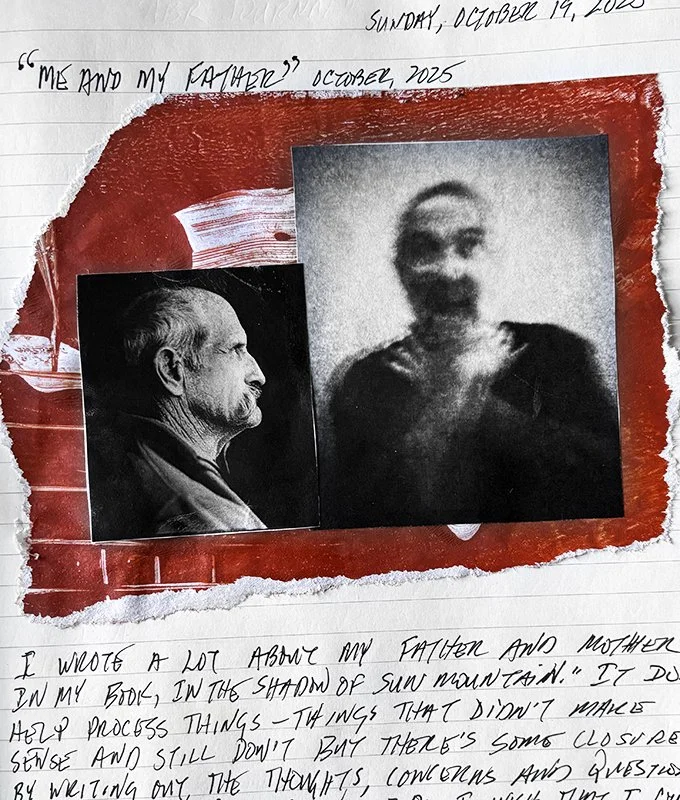

Journal entry - October 2025.

At the same time, I’ll be studying how others respond to this work and what happens psychologically, symbolically, and emotionally when someone encounters artwork that doesn’t look away from mortality. Death denial shows up in recognizable ways: humor, defensiveness, projection, avoidance, and philosophical distancing. But sometimes something deeper appears: recognition, quiet, even a brief moment of meaning.

ABR gives me a structure to study all of this.

My own creative process.

The images that emerge.

The responses they evoke.

The symbolic patterns that repeat.

The ways meaning cracks open or closes down.

It lets me bring the studio, the psyche, and the research questions into one integrated space.

My hope is to create a body of work that matters both inside academia and beyond it. Art isn’t an accessory to life; it’s a method of survival. Artists metabolize things the culture doesn’t know how to hold directly. We take fear, grief, rupture, and turn them into form, into symbols that others can bear to look at. It isn’t therapy and it isn’t escape. It’s a form of existential transformation.

If I can articulate that process, what it feels like, what it reveals, and how it shapes both the maker and the viewer, then the work will have done something meaningful. It will help explain why creative practice is one of the most honest responses we have to our own mortality.

So that’s the direction I’m heading: a reworked Sun Mountain, a sequence of manuscripts that build the conceptual ground, a new exhibition, and a dissertation that uses arts-based research to study the artist’s encounter with mortality from the inside out. I’m building an integrated body of work, creative, philosophical, and experiential, that examines what it means to be mortal and how artists turn that reality into meaning.

More will unfold as the work begins to take shape.

Untitled—Whole Plate Salt Print from a wet collodion negative.

When I pull a print like this from the wash, I think about presence, the way it clings for a moment before fading (not fixed). The chemistry stains, the brush strokes at the edges, and the paper that curls in my hands—none of it is meant to last. That’s what I love about it. It’s a print that remembers its making. The figure still feels fragile, but now it’s suspended in a kind of quiet acceptance.

Living Truthfully Inside Impermanence

Rupture is not simply a wound; it’s the generative moment when denial collapses and creation begins. It’s the place where death anxiety, cultural myth, and personal memory are transmuted into presence. Within rupture, the artist becomes a witness rather than a defender, turning from the fantasy of permanence toward the truth of impermanence. In that shift, art no longer seeks to outlive death; it becomes a form of living with it.

Otto Rank’s distinction between the artist and the neurotic illuminates this process. Both encounter rupture, the psychic shattering that comes when one’s symbolic world no longer holds, but only the artist metabolizes it. Where the neurotic internalizes and chokes on anxiety, the artist transforms it into form. The creative act becomes a means of surviving truth, of remaking coherence in the face of its undoing. Ernest Becker described culture as a shield against mortality; I see art as the moment that shield cracks. The fracture is not failure but revelation, an aperture where something honest can enter.

My work with wet collodion lives inside that aperture. The process itself enacts rupture: collodion, glass, silver, and time. Each plate holds the risk of loss. The collodion might peel, the image might fog, and the light might fail. Yet those failures become evidence of life. The surface bears the marks of both fragility and endurance, transparency and strength. Each plate is a negotiation between control and surrender, between the impulse to preserve and the inevitability of decay. To work in this way is to accept that every act of making is also an act of unmaking. I’m connecting deeply to these ideas and am excited to see where it takes me.

“Choking on Rocks.” Whole-plate wet collodion negative, made in the New Mexico desert, 2025. The plate holds the brief intersection of flesh, glass, and stone, an encounter with what endures and what disappears.

Between Presence and Absence

This new whole-plate wet collodion negative feels less like a photograph and more like a question: what does it mean to hold presence and impermanence in the same breath? The man, the bottle, and the rocks: are they material, or are they ghosts caught in the alchemy of silver and collodion? The glass doesn’t just capture an image; it captures the residue of time passing. What remains when the moment is gone? What does the plate remember that we forget?

Collodion always reminds me that everything we try to fix eventually fades. The process is slow and ritualistic; it forces me into a state of attention. Light becomes a witness, not just a means. This plate, like so many I make, isn’t about nostalgia; it’s about the impossibility of permanence. It’s about standing inside the paradox that Becker, Rank, and Yalom each described in their own way: to create in the face of death is both defiance and surrender.

In that sense, this image is elegiac. The man’s presence feels temporary, the bottle reflective, and the rocks ancient and indifferent. Together they form a kind of visual equation, human transience measured against geological time. The silver surface, with its imperfections and streaks, becomes a metaphor for the self: luminous, decaying, still reaching toward meaning.

Racism isn’t innate – Here are Five Psychological Stages that may Lead to It

I encourage you to take a look at this article from The Conversation. It references Terror Management Theory, which to me is one of the most overlooked—and ignored—frameworks for understanding the problems we face today.

From racism to war, from bigotry and xenophobia to jingoism and religious dogma, we seem almost determined to find “the other.” As the old saying goes, I’ll hate you for the color of your shirt or the shape of your nose. Anything will do, so long as it puts someone in the “out group.” America has been marinating in this for a long time, and at this moment, I don’t see the future looking particularly bright. If anything, I’d caution people to prepare themselves for more, and larger, terrible events ahead.

You can already see it unfolding: Russia’s war in Ukraine, the genocide in Gaza, and climate disasters that grow more relentless each year—wildfires, hurricanes, and flooding. These events are not only catastrophic in themselves, but they remind us, again and again, of our own fragility and mortality. And when we are forced to face that, death anxiety tends to boil over into hostility, scapegoating, and division.

“We spend endless energy on the ‘what’ of our problems but rarely ask the ‘why.’ It’s like treating a cough while ignoring the virus that causes it.”

Add to this the terrible political divide in America: the Kirk assassination, Trump sending troops into American cities, and the daily drumbeat of culture war rhetoric. Political party loyalties—red and blue alike—are tearing at the fabric of our society. Even in our everyday lives, people seem more standoffish, impatient, and cold (I’ve felt this for a few years). It’s as if the collective weight of death anxiety is bubbling up everywhere, pushing us further into our corners.

This is what my studies and interests revolve around: what the fear of non-existence means for people and how it runs outside of conscious awareness. Terror Management Theory and Ernest Becker’s work hold so much explanatory power, I can’t understand why more people don’t embrace them—don’t bring them into their lives. Our world would be a much better place if we did.

Sheldon Solomon, building on Becker, put it bluntly: We will always need a designated group of inferiors.

What do you think? Do you see this drive to divide and “other” playing out in your own circles, communities, or even in the way strangers treat each other on the street? I’d love to hear your perspective.

And yet, I can’t help but believe there’s another path. If we had the courage to face death honestly, maybe we wouldn’t need enemies at all.

Picacho Hills early August morning. Las Cruces, New Mexico 2025

The Explanatory Power of Becker's Ideas and TMT

On the first page of Ernest Becker’s book, The Birth and Death of Meaning (1962), he wrote, “This is an ambitious book. In these times there is hardly any point in writing just for the sake of writing: one has to want to do something really important. What I have tried to do here is to present in a brief, challenging, and readable way the most important things that the various disciplines have discovered about man, about what makes people act the way they do.”

Terror Management Theory (TMT), developed as an extension of Ernest Becker’s work, posits that the uniquely human awareness of mortality gives rise to profound existential anxiety. As Becker argued in The Denial of Death (1973), this awareness creates the potential for paralyzing terror that must be managed if life is to remain bearable. To buffer against this anxiety, individuals construct and maintain cultural worldviews that provide meaning, order, and the promise of personal significance. These worldviews not only orient individuals within a shared reality but also serve as symbolic defenses against death anxiety. Consequently, human motivation is fundamentally tied to sustaining the belief that life has purpose and that one’s existence has value. When these worldviews are challenged—or when mortality becomes salient—individuals typically respond with defensive strategies aimed at reestablishing confidence in their cultural frameworks and reaffirming their sense of worth.

This is where my work enters the conversation. If culture at large defends us against mortality, art can turn toward it. My work is centered on art that metabolizes death anxiety into meaning—not by escaping it, but by dwelling in its presence. Over the next three years, I will be creating both a dissertation and a body of work that explore how creativity can transform existential dread into something we can live with, and maybe even live more fully because of it.