I've been thinking about what happens to meaning when we can no longer justify our work by its output.

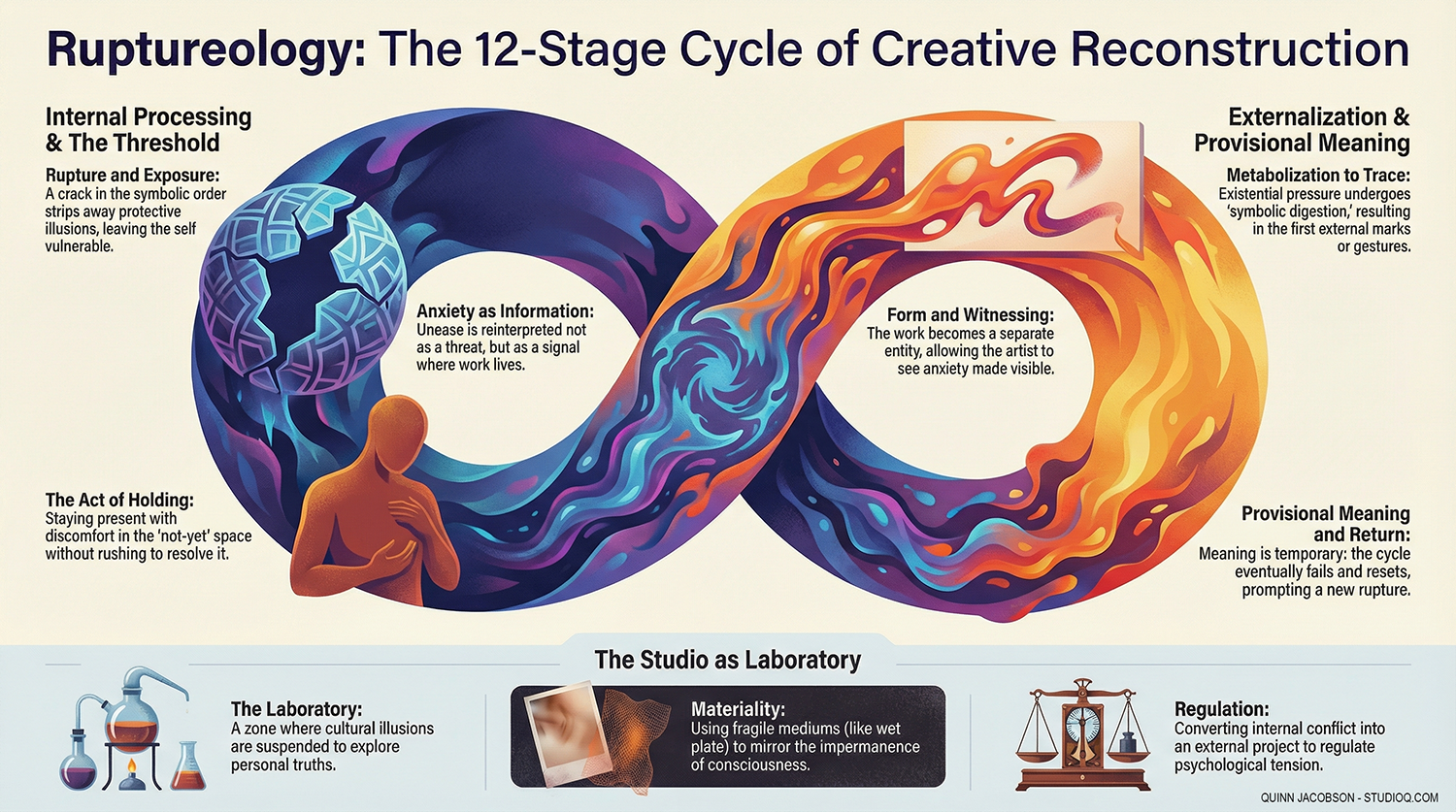

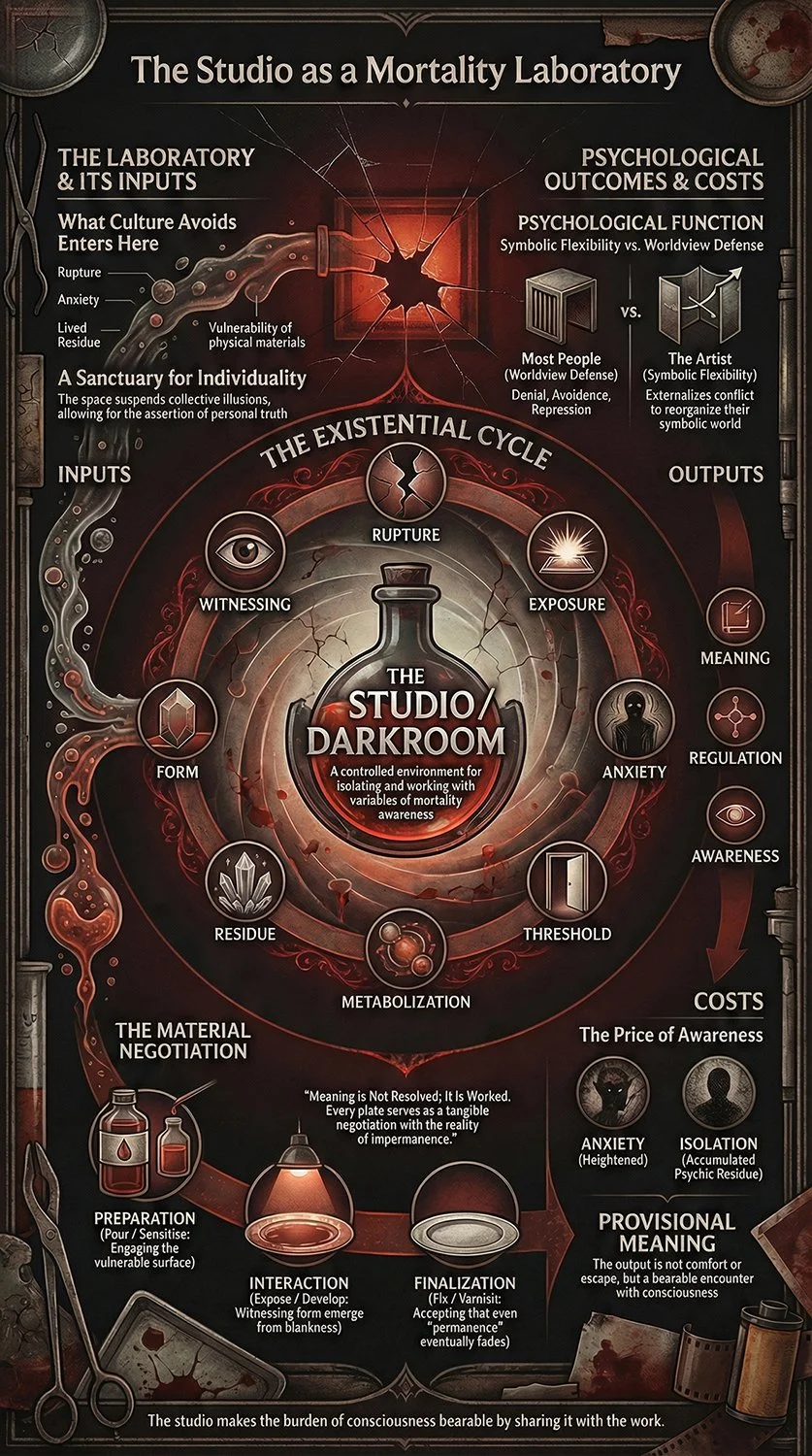

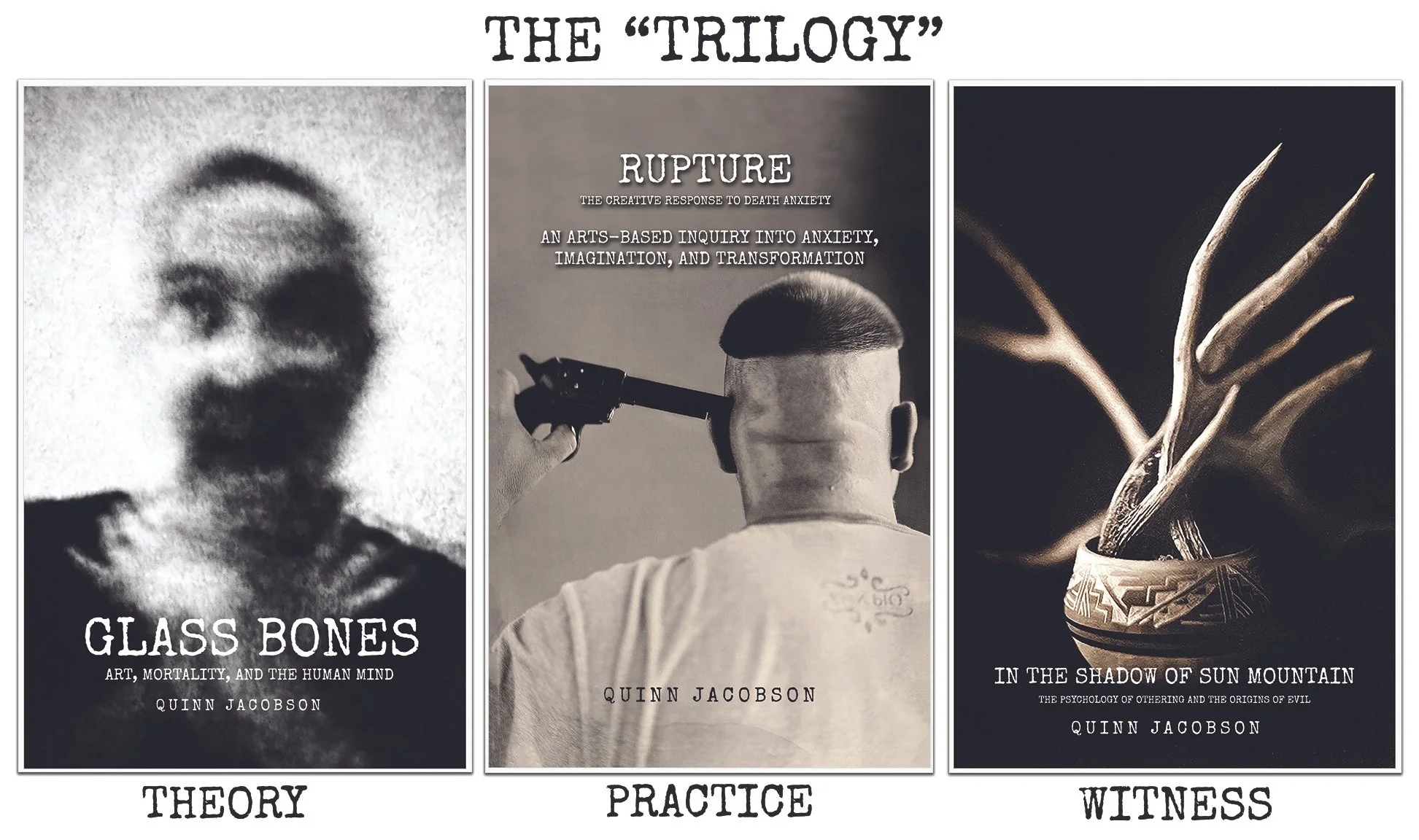

For the past several years, I've been researching the relationship between creativity and mortality, how artists use their practice to metabolize the knowledge of death. The work draws heavily on Ernest Becker's The Denial of Death and Terror Management Theory, which argue that much of human culture functions as a defense against existential terror. We build, we make, and we leave marks, not just to create beauty or communicate ideas, but to convince ourselves we matter in the face of annihilation.

But what happens when artificial intelligence can produce those marks faster, better, and without the mortal stakes that gave them weight?

As a doctoral student, I am currently preparing to write a dissertation that has taken years to research and work through. If I'm honest, I'm also someone who's started asking, "Why am I doing this when AI could knock out a more comprehensive version in an hour?” Or, “Why spend months in the studio wrestling with fragile nineteenth-century photographic chemistry when an algorithm can generate a comparable image in seconds?” Why make anything at all when machines can produce better books, paintings, and theories without effort, without mortality, and without stakes? This is the edge I'm working from now.

This isn't about Luddism or nostalgia. It's an existential question. If the things we make no longer function as proof of our significance, what's left?

The traditional answer from Terror Management Theory is that creativity serves as a form of symbolic immortality. We make things that outlast us. We contribute to a field, leave a body of work, and inscribe ourselves in culture. But AI destabilizes that entire framework. If machines can produce superior contributions without bodies, without death, without the mortal urgency that supposedly drives human creativity—then what was our work ever really for?

I think the answer is hiding in the materials.

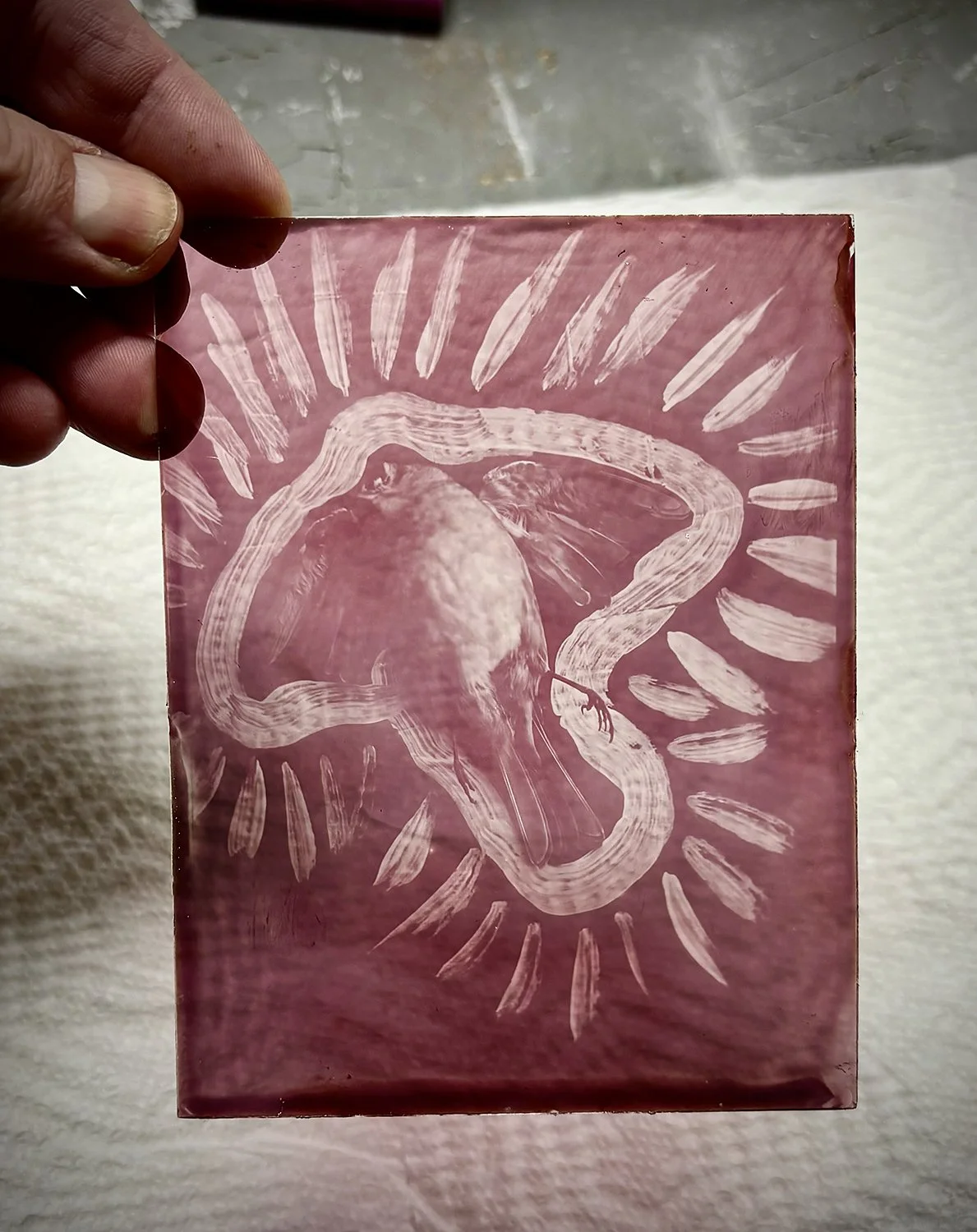

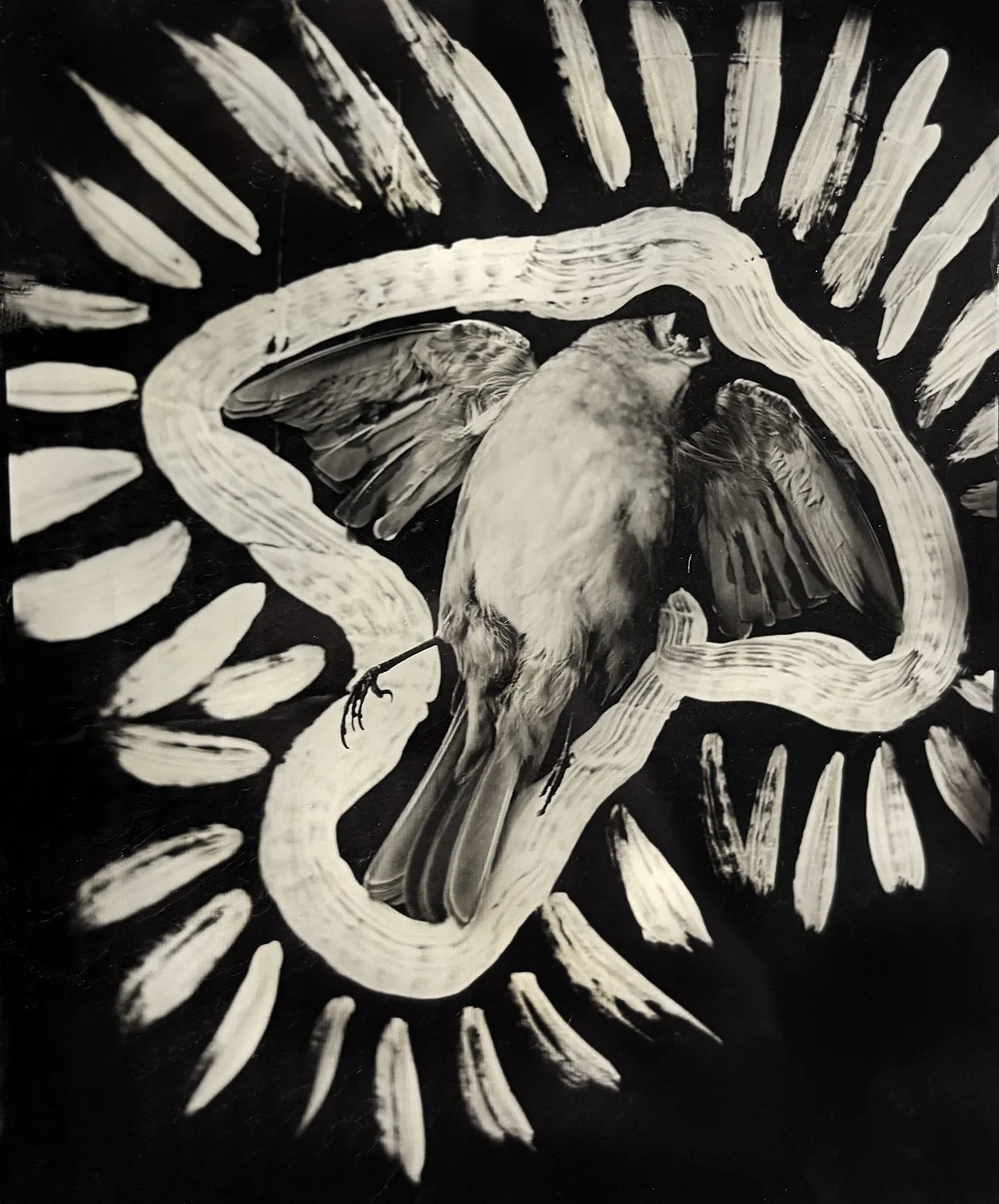

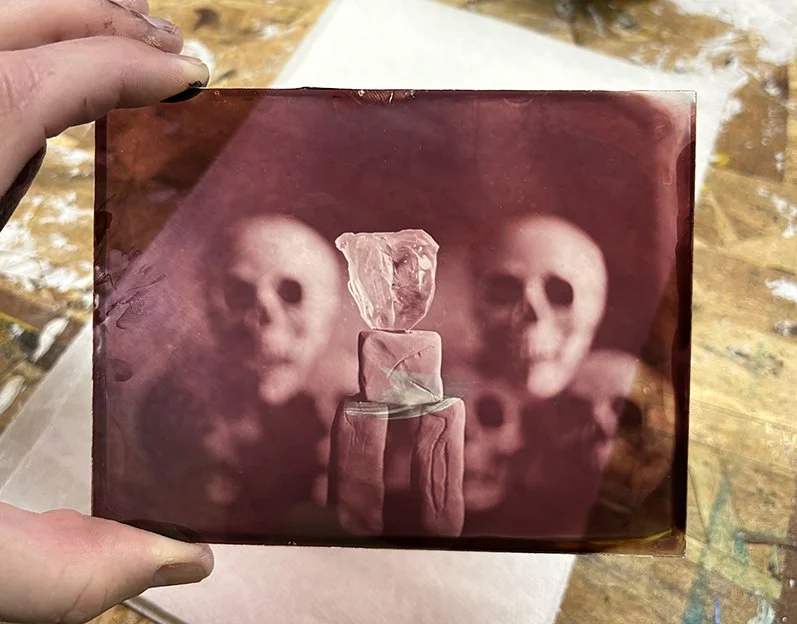

I work with wet plate collodion, a photographic process from the 1850s that involves pouring light-sensitive chemistry onto glass, exposing it while still wet, and developing it immediately. It's slow, unpredictable, and failure-prone. Plates crack and break, and collodion lifts and peels. Silver fogs. Images are damaged. I also paint, and I've started treating my studio as a research site. The material disruptions are not a hindrance but rather an integral part of the process. The cracked plates, the unruly paint, and the collapsing sculptures are not mistakes. They're data. They're evidence of what it means to make something while subject to physics, time, and entropy.

AI doesn't experience this. It can generate images, text, and even simulations of failure. But it doesn't confront materiality the way a mortal body does. It doesn't feel the anxiety of a plate that might not develop, the exhaustion of revising a chapter for the eighth time, or the vertigo of realizing your entire theoretical framework is wrong and you have to start over. It doesn't live with the knowledge that the work will end because you will end.

I'm starting to think the meaning was never in the output alone. It was in the mortal struggle with the medium. The labor of a finite being attempting to say something true before time runs out. The refusal to look away from fragility: ours, the world's, the image's, and the decision to create anyway.

This doesn't resolve the problem. If anything, it makes it sharper. Because if meaning lies in embodied, mortal labor, and if AI can produce everything that labor once produced without the body or the mortality, then we're facing something far more unsettling than obsolescence. We're facing the possibility that human meaning-making itself becomes optional. A kind of performance. A choice to keep doing something the hard way when the easy way is infinitely more efficient.

Maybe that's where we are. Maybe the question isn't whether AI will replace human creativity, but whether we can bear to keep making things when there's no instrumental reason left to do it. When the only justification is the confrontation itself, the fact that we are mortal creatures insisting on witness, on presence, on the stubborn act of leaving a mark even when we know it won't matter in any measurable way.

I don't have an answer. But I keep coating plates. I keep writing. I keep working with materials that crack and fail and resist me, because the meaning isn't in whether the work is better than what a machine could produce. The meaning is in the fact that I did it. That I was here. That I chose to create not as a defense against death, but as a way of staying honest about it.

If AI can make everything, then maybe what remains for us is the one thing it can't do: be mortal, be afraid, and make something anyway.

“The Outline and the Drift,” half-plate Collodio-Chloride print on glass from a wet collodion negative. This is pre-fix - what a beautiful color.