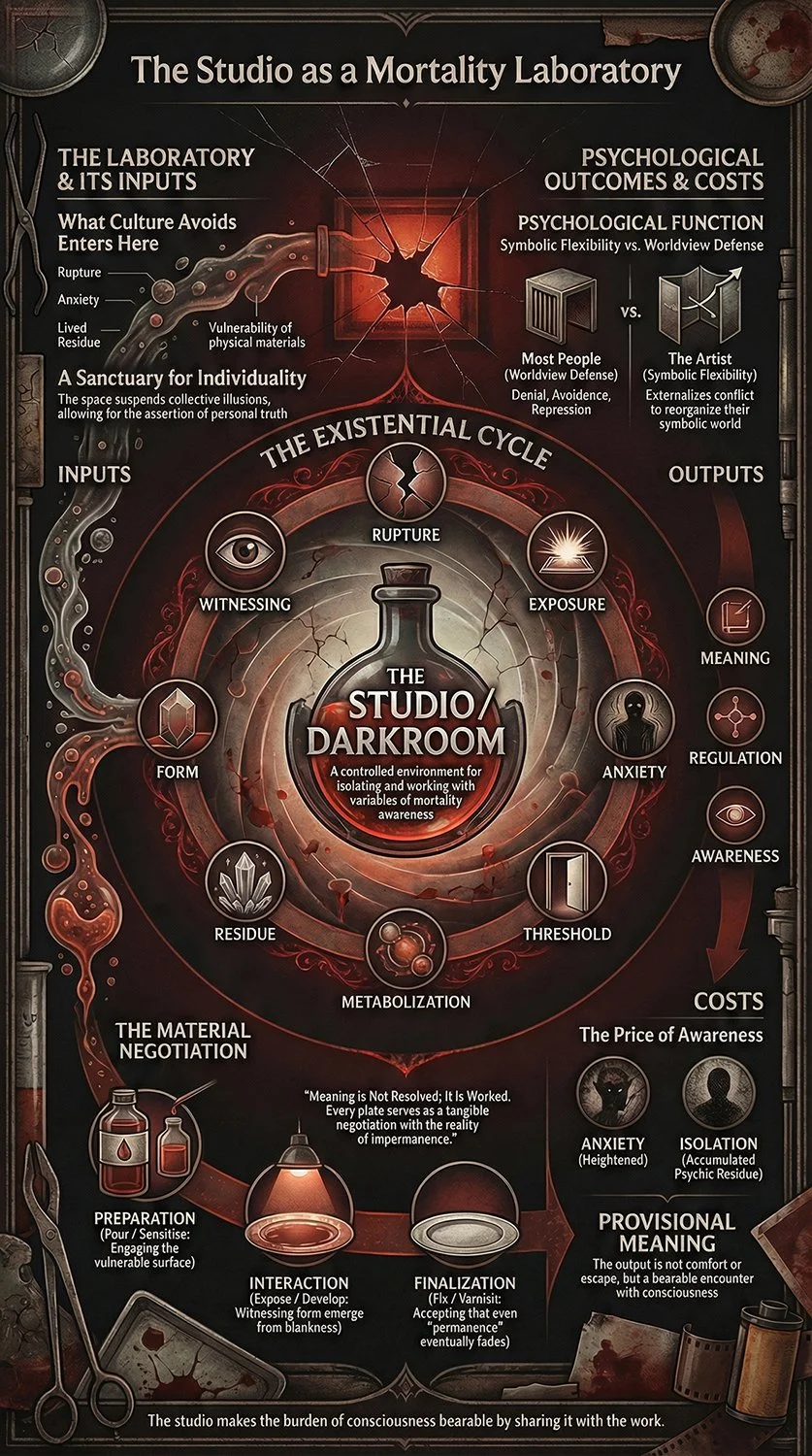

Artists metabolize existential pressure while others defend against it. Existential pressure is the psychological force generated when awareness of mortality, impermanence, and the constructed nature of meaning exceeds the capacity of denial to contain it.

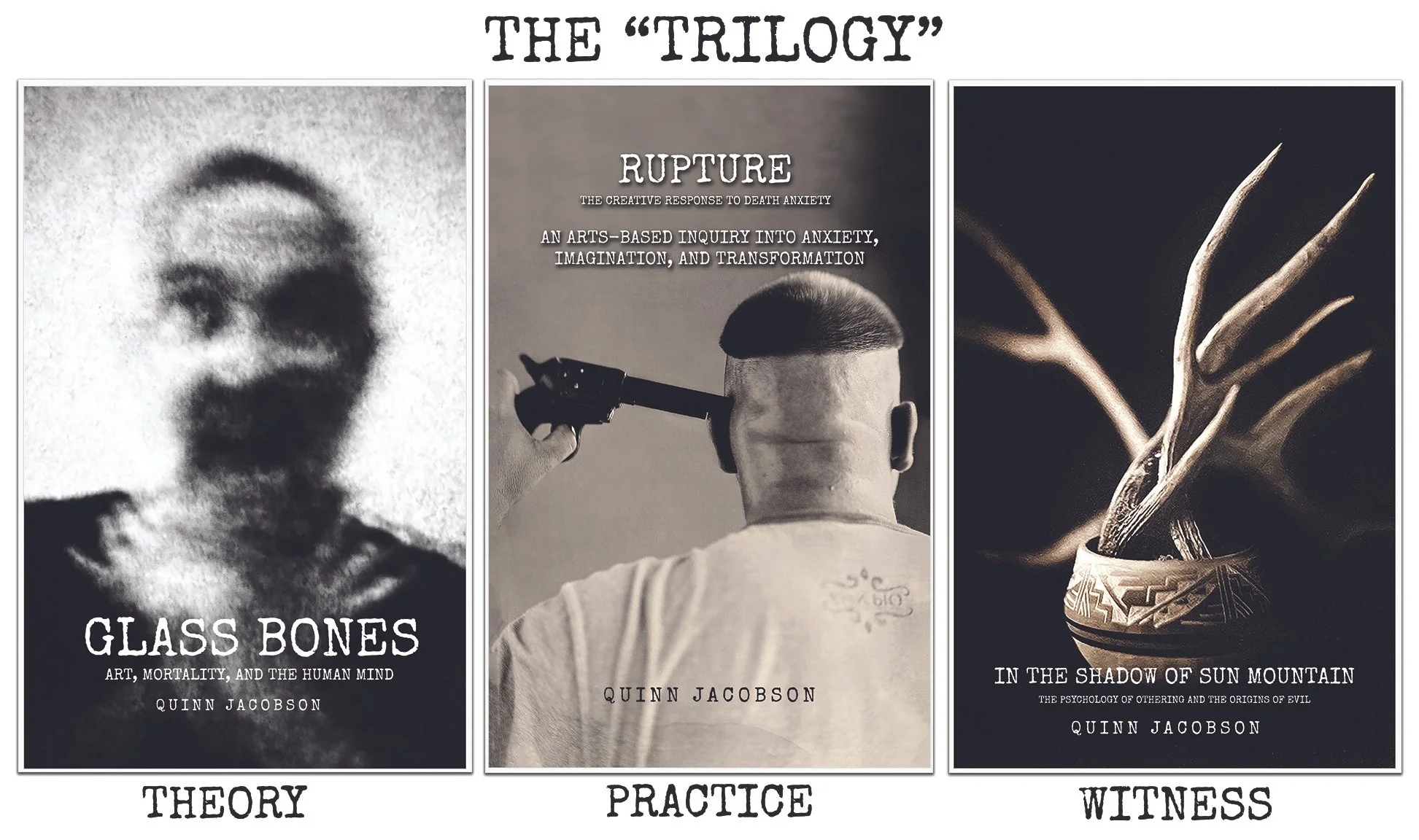

Rupture as Lived Experience: A Phenomenological Inquiry into Creative Meaning-Making.

This is a brain dump of ideas I’m playing with as I develop this idea around my creative experience. In a nutshell, questions and comments about what happens and why.

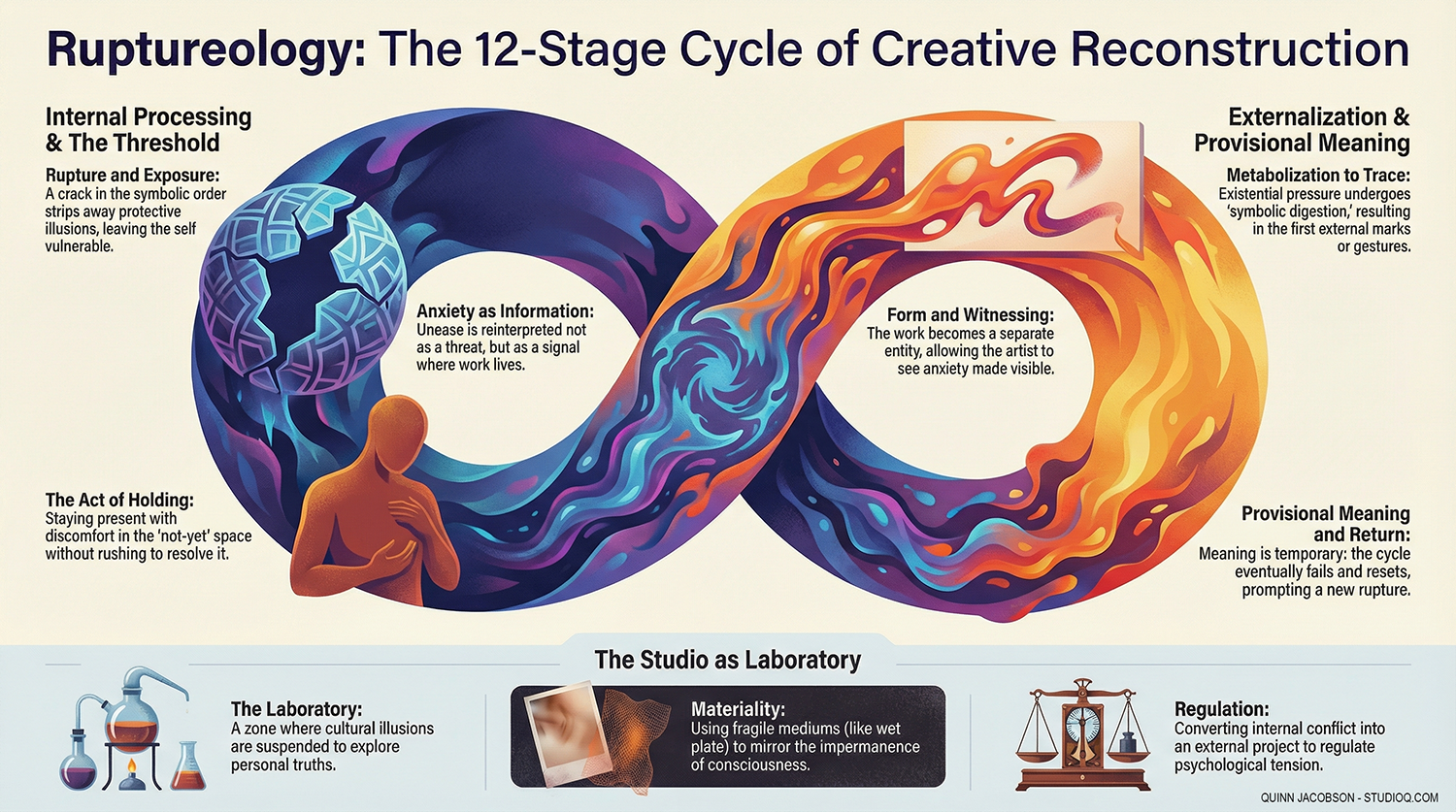

1. RUPTURE

What it is:

Something breaks when a belief, identity, relationship, certainty, or sense of meaning no longer holds.

What it feels like:

The experience can be characterized by shock, disorientation, grief, or a sudden thinning of reality.

Example:

A death. A creative block remains unresolved. Boredom. Frustration. Realizing the story you’ve lived by no longer fits your life.

2. EXPOSURE

What it is:

The protective stories fall away. You see something you were previously shielded from.

What it feels like:

Rawness. Vulnerability. The sense of being “too open.”

Example:

Sorting through a box of family photographs after a death, you realize the images aren’t preserving anyone. They’re evidence that preservation fails. The camera didn’t stop time. It only recorded its passing.

3. ANXIETY

What it is:

The nervous system responds to exposure. This is not pathology; it’s the body registering uncertainty.

What it feels like:

It manifests as restlessness, dread, agitation, and an urgency to either fix or escape.

Example:

You may find yourself wanting to distract yourself, overthink the work, or abandon it entirely.

4. THRESHOLD

What it is:

It represents a critical juncture where one must choose between avoidance and staying.

What it feels like:

Tension. There is a feeling that a significant event could occur or potentially fail.

Example:

You enter the studio anyway. You sit with the materials instead of turning away.

5. HOLDING

What it is:

It involves staying present and not rushing to resolve the discomfort.

What it feels like:

Uncomfortable steadiness. It's not a state of calmness, nor is it one of flight.

Example:

The individual persists in their work despite the lack of progress.

6. METABOLIZATION

What it is:

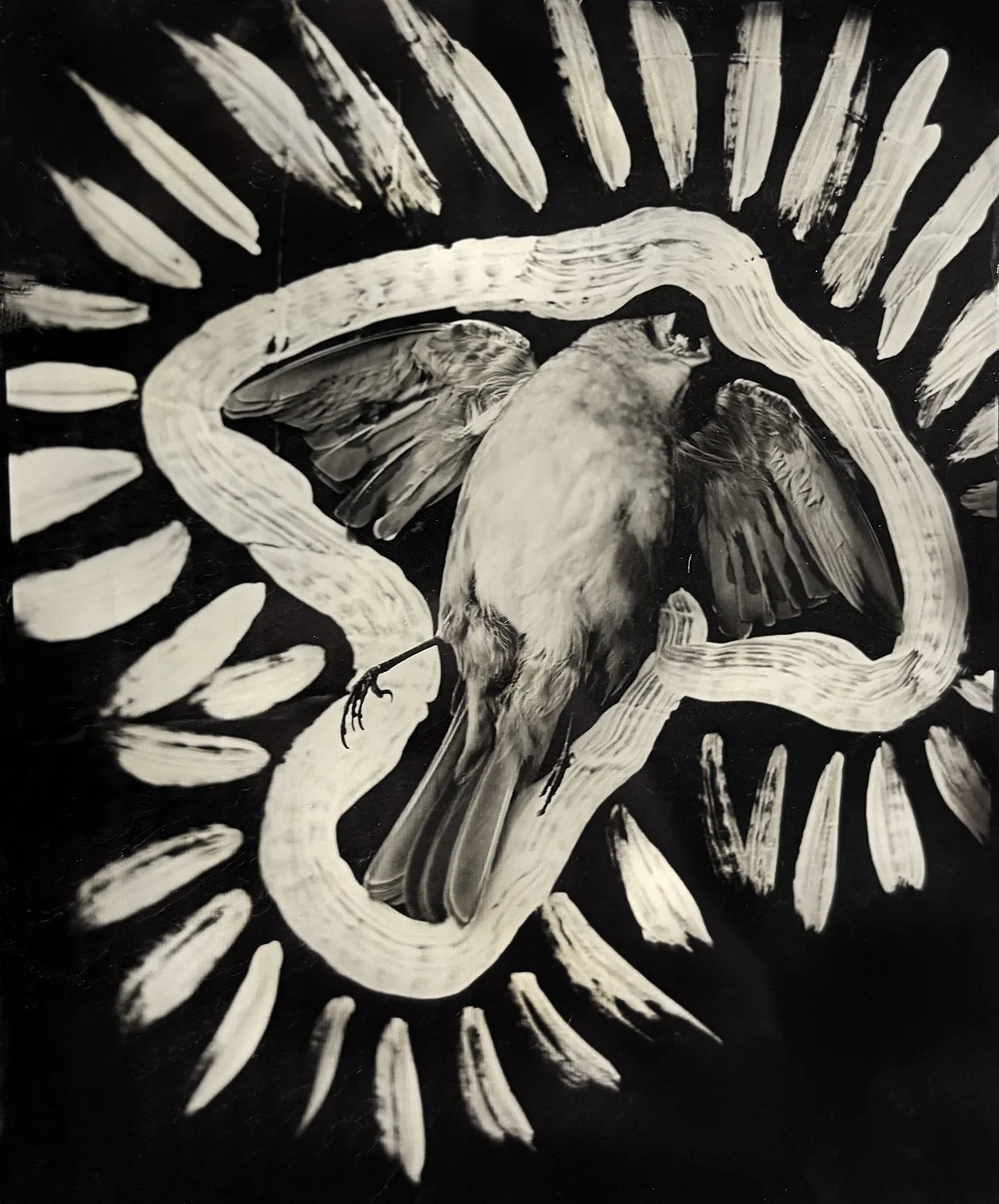

The rupture begins to be processed through action, material, repetition, and attention.

What it feels like:

Engagement replaces paralysis.

Example:

You remake the image again and again, not because the first one failed, but because the act of remaking stabilizes something internally. Repetition becomes containment.

7. RESIDUE

What it is:

The residue is what remains after exposure has passed through the body and into matter.

What it feels like:

Traces rather than answers.

Example:

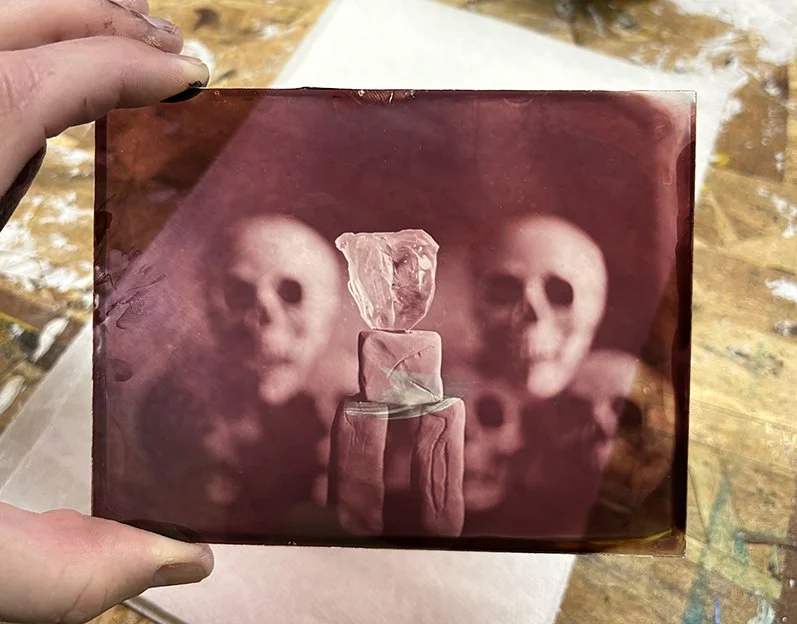

Examples include stains, cracks, discarded drafts, broken plates, and half-formed ideas.

8. TRACE

What it is:

The first visible sign that something is taking shape.

What it feels like:

Recognition without clarity.

Example:

An image emerging in the developer. Suddenly, a phrase resonates with truth.

9. FORM

What it is:

The work coheres enough to stand on its own.

What it feels like:

Provisional stability.

Example:

A finished plate, painting, or piece that carries more than you consciously intended.

10. WITNESSING

What it is:

You step back and encounter what you’ve made as something separate from you.

What it feels like:

Surprise. Sometimes discomfort. Sometimes relief.

Example:

Seeing the work and realizing it knows something you didn’t know how to say.

11. PROVISIONAL MEANING

What it is:

Meaning emerges—not as certainty, but as something livable.

What it feels like:

Enough ground to stand on, for now.

Example:

Understanding that the work isn’t about solving death but learning how to stay in relationship with it.

12. RETURN (TO RUPTURE)

What it is:

Meaning never seals the system. Life introduces the next rupture.

What it feels like:

Familiarity with instability.

Example:

The next plate breaks. The next loss arrives. The cycle begins again.

Ruptureology describes how meaning is not found by avoiding breakdown but by staying with it long enough for form to emerge.

These questions are not meant to test a theory, measure outcomes, or confirm a model. They are descriptive prompts designed to invite artists to speak from experience, in their own language, about what actually happens for them in moments of rupture and creative work. The sequence reflects a pattern I have observed in my own practice over decades, not a set of steps anyone should follow. Artists may recognize parts of it, skip others entirely, or describe the same experiences in different terms. The value here is not alignment, but articulation. This is an inquiry into how creative work is lived from the inside, especially when meaning breaks down, rather than a framework imposed from the outside.

Ruptureology

Open-ended prompts for conversation, not data collection

1. Rupture

Can you recall a moment when something in your life or work stopped making sense in the way it used to?

What tends to bring you into the studio during those times?

2. Exposure

When that kind of disruption happens, do you feel more open, raw, or sensitive than usual?

How does that show up for you when you’re working?

3. Anxiety

What happens in your body or mind when things feel uncertain or unresolved in the work?

Do you notice urges to fix, avoid, distract, or control at that stage?

4. Threshold

Is there a moment when you’re deciding whether to stay with the work or step away from it?

What helps you cross that threshold, if you do?

5. Holding

How do you stay with the work when it’s uncomfortable or unclear?

What does “not knowing” feel like for you in the studio?

6. Metabolization

At what point does working with materials start to feel like it’s doing something for you, even if you can’t name what that is yet?

Are there repetitive actions or rituals that seem important here?

7. Residue

After working through something difficult, what tends to be left behind?

Do unfinished pieces, discarded materials, or failed attempts matter to you?

8. Trace

Can you describe the moment when you first sense that something is beginning to emerge?

How subtle or tentative is that moment, usually?

9. Form

When a piece starts to take shape, how does that change your relationship to what you were working through?

Does the work ever surprise you?

10. Witnessing

What is it like to encounter the finished (or nearly finished) work as something separate from you?

Do you recognize yourself in it, or does it feel like it knows something you didn’t?

11. Provisional Meaning

Does the work ever give you a sense of meaning or orientation, even temporarily?

How stable or unstable does that meaning feel?

12. Return

After a piece is finished, what tends to happen next for you?

Do similar disruptions return in new forms?

Closing

If you had to describe what the studio does for you when life or meaning feels unstable, how would you put that in your own words?