Coyote carcass on desert dirt, Las Cruces, New Mexico, November 2025. Photograph by Quinn Jacobson.

The Coyote That Died on My Land

A couple of days ago, I caught a strong smell outside while working on a photograph. It was sharp, pungent, and unmistakable. Death has a particular odor that bypasses thought and goes straight to the gut. It made me queasy for a moment. Human death is worse; its scent lingers in your psyche as much as your senses, but this was still hard to shake.

I live on two acres, so it could’ve been anywhere. But the breeze was steady from the south, and the smell was heavy enough to trace. I didn’t walk a hundred feet before I saw it: a coyote, fully grown, laid out in the dirt as if sleep had taken it mid-motion. I hear them often at 4 a.m. Their calls ricocheting through the desert, a chorus of wild life that reminds me I’m not alone out here. They’re ghosts most of the time, heard but rarely seen.

My first instinct was to call animal control. But after thinking about it, I decided to leave the body where it was. Nature doesn’t need me to manage it. I’ll let it return to itself. When the flesh is gone and the bones are bare, I’ll bring them into my studio and make photographs.

For me, that act isn’t about morbidity; it’s about continuity. As Ernest Becker wrote, “All organisms are torn between the desire to live and the knowledge that they must die.” This coyote’s death is part of the same existential equation that drives art. Otto Rank saw art as the individual’s answer to mortality, a symbolic act of defiance, and an assertion that something of us can endure. Terror Management Theory later confirmed it empirically: the awareness of death propels us to create meaning, to build culture, and to leave traces that say we were here.

The coyote reminds me that no creature escapes this truth. Yet, there’s a strange grace in its stillness. The desert will do what it’s always done; it will metabolize the body, slowly, beautifully, until there’s only bone and dust. In that process, I see a mirror of the creative act: transformation through decay.

In time, I’ll photograph what remains—not as documentation of death, but as witness to the cycle that keeps everything alive.

Theory Note: Death, Art, and the Creative Instinct

Becker believed that culture, and by extension, art, is humanity’s way of managing the terror of mortality. We build symbolic worlds to convince ourselves that our lives matter, that something of us endures beyond the grave. Otto Rank expanded this idea, seeing the artist as a kind of “hero of creation,” transforming existential anxiety into symbolic immortality through the act of making. Terror Management Theory offers the scientific echo: when reminded of death, people turn to creativity, meaning, and worldview defense to restore equilibrium.

This coyote, in its silent return to the earth, embodies what Becker, Rank, and the TMT researchers all touch upon: the dance between decay and creation. In death’s presence, we’re reminded why we make anything at all.

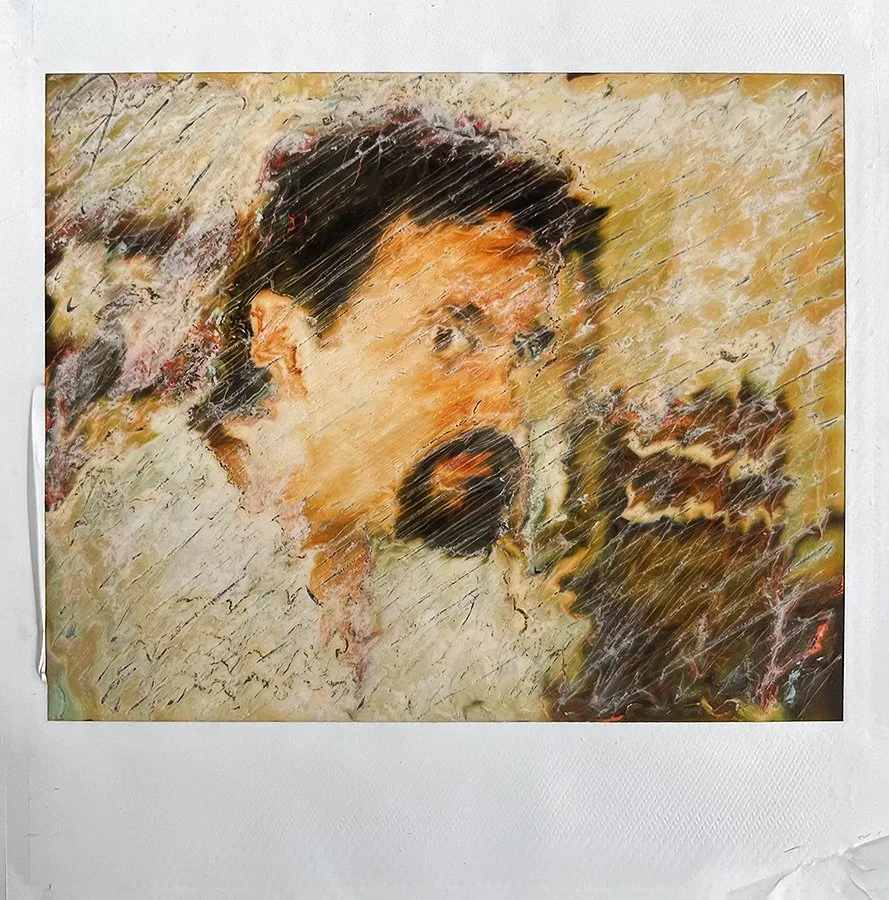

“Ode to Van Gogh,” manipulated Polaroid. 1993. Part of the Visions in Mortality exhibition.

From Visions in Mortality to In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: Tracing a Life’s Work

In 1993, I put together a small exhibition called Visions in Mortality. At the time, I didn’t know Ernest Becker’s work, I hadn’t read The Worm at the Core (Terror Management Theory), and Ajit Varki and Danny Brower’s book Denial was still years away from being published. But even without the theory, I knew where my compass pointed. I wanted to make art about death anxiety and existential struggles.

Looking back now, those photographs feel like an instinctive first attempt to break through the evolutionary wall of denial. I didn’t have the language for it then, but what I was doing was confronting the thing most of us spend our lives avoiding. The work wasn’t about distraction or comfort—it was about holding mortality in front of myself and anyone willing to look.

That exhibition planted a seed. It revealed what would become the through-line of my entire practice: how do we live, create, and remain human in full awareness of our impermanence?

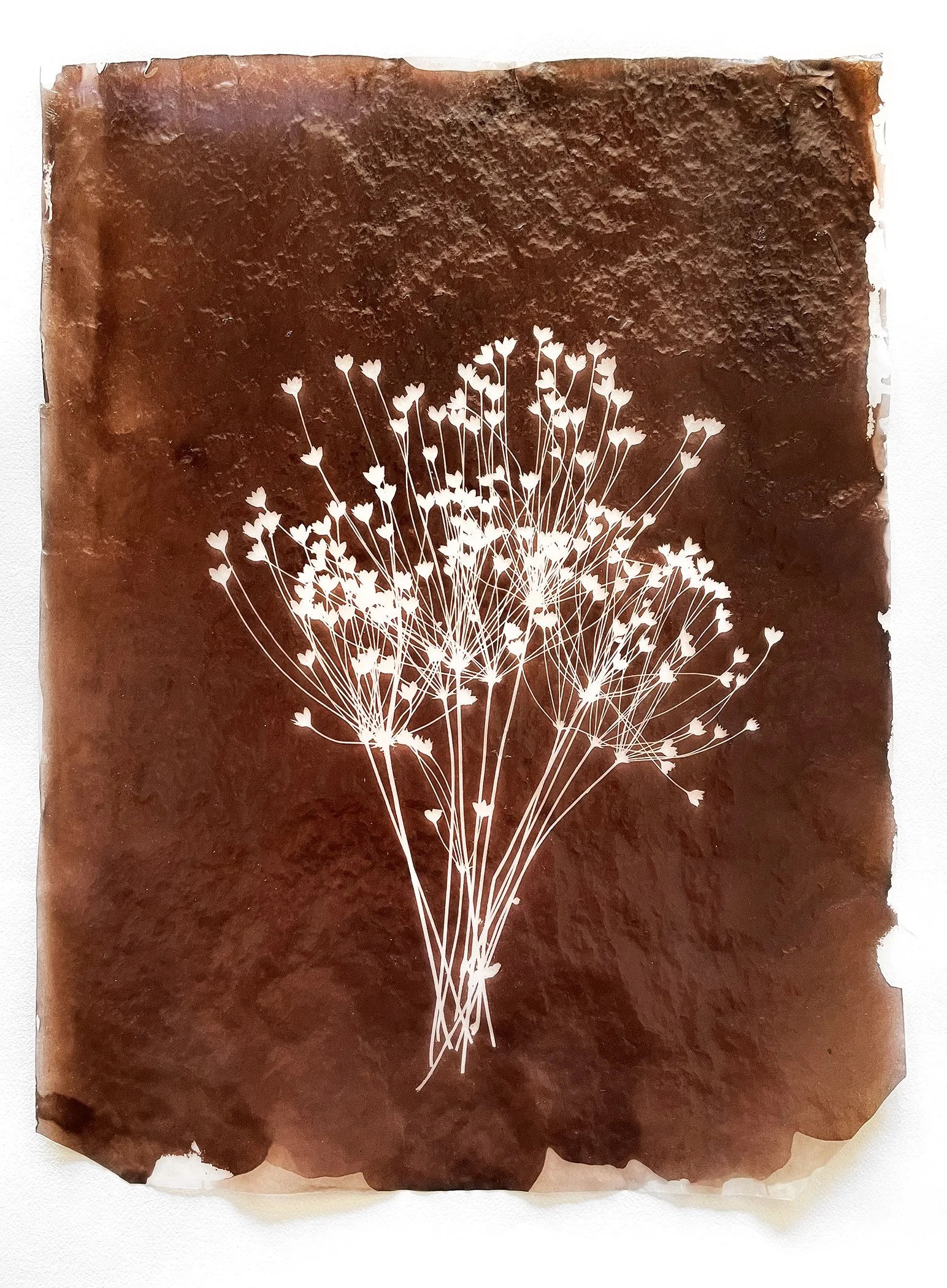

“Gone to Seed,” Whole Plate Photogenic Drawing on vellum paper (waxed). The work was created in 2022 as part of the project titled, “In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of Othering and the Origins of Evil.”

Three decades later, In the Shadow of Sun Mountain is the mature expression of that same impulse. Where Visions in Mortality was raw, direct, and almost primal, Sun Mountain is layered—woven through with Becker’s insights on cultural worldviews, TMT’s evidence of our defensive psychology, and Varki and Brower’s claim that denial itself had to evolve in order for us to function as conscious beings.

The difference is scope. Visions in Mortality was a solitary confrontation with death, denial, and culture. Sun Mountain is a confrontation with collective denial—the way cultures rewrite history, erase peoples, and commit violence (genocide) in the name of permanence. It’s about how our fear of death doesn’t just haunt us as individuals but shapes entire societies.

But the continuity matters more than the contrast. Both projects spring from the same recognition: that art is one of the few places where denial can falter, where we can face mortality directly without looking away. That has been my practice from the beginning, whether I had the theory to explain it or not.

Now, in my doctoral studies, I’m taking this inquiry a step further. I’m asking not only how artists confront mortality differently than others, but also what that confrontation makes possible—for art, for ethics, and for the way we live together. If Visions in Mortality was the initiation and Sun Mountain the culmination, this research is the extension. It’s an attempt to turn decades of practice into a framework that others—artists, scholars, anyone willing to face the void—can use to think differently about mortality, meaning, and art.

Visions in Mortality was the beginning. Sun Mountain is the continuation. The dissertation will be the next turn in the spiral—returning to the same question from a higher vantage: what does it mean to create, to love, to exist, knowing all along that the universe is indifferent and that everything vanishes?

“Friedhof Käfertal” Whole plate Albumen print from a wet collodion negative. 2009

When Death Isn’t Just Biology

What are humans afraid of? Death, meaninglessness, loneliness (isolation), and freedom. Ernest Becker and Jean-Paul Sartre made that abundantly clear.

We prefer to act as though death is easy. Vital signs, brain scans, organ failure—we turn it over to the biologists. We say, "This is where life ends," and draw a clear line. In actuality, however, human death does not exist in the sterile realm of checklists and charts. It inhabits the world of stories and symbols.

We are frightened by more than just the body shutting down. It is the breakdown of a life dominated by others. We are held to our flimsy promises of immortality by the cutting of ties. Few people knew this better than Ernest Becker. He observed that we create our morals, our art, and our cultures as defenses against the inevitable death. We try our hardest to hide that terrible reality and to act as though our existence is more than a passing biological fad.

It is possible to declare a body on a ventilator brain-dead. It's done biologically. However, to the living, it can still be a person, a narrative, or a strand in the web we weave to keep the abyss at bay. This is painfully evident from the paper I just read: human death is always relational, moral, legal, and practical. It is more than a simple off/on switch. It marks the end of a "life-form," a life molded by ritual, language, memory, and the vows we make to one another.

There is more than just flesh left over after a death. The tangle of obligations, relationships, and rights that keeps the deceased in our world a little while longer is all that is left. Even if they only endure as long as the memory does, they continue to firmly ground us in our denial and our attempt at symbolic immortality.

The moment when our symbolic world finally breaks and we realize that all of our illusions and buffers can only last so long may be the true threshold that we fear, rather than the boundary between flatline and heartbeat.

“The idea of death, the fear of it, haunts the human animal like nothing else; it is a mainspring of human activity—activity designed largely to avoid the fatality of death, to overcome it by denying in some way that it is the final destiny for man.”

— Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death

What do you see holding your fear of death at bay? Do you lean on something? Or are you in a free-fall state of neuroticism? Afraid of both life and death?

“Rocky Mountain Cotton,” 8” x 10” cyanotype on vellum paper (waxed). 2022

Facing the End: Heidegger, Modernity, and the Meaning We’ve Lost

We don’t really talk about death anymore—not in any meaningful way. We dress it up in ritual, drown it out with noise, and spin it into spectacle. Somewhere along the way, we stopped treating death as a mirror and started treating it like a mess to be cleaned up. But as Martin Heidegger once argued, our relationship to death isn’t just a philosophical curiosity—it’s the foundation of an authentic life.

In Being and Time, Heidegger introduced a concept that should hit all of us squarely in the gut: Being-towards-death. Unlike animals, humans are aware of their own mortality. We don’t just die—we know we’re going to die. And that knowledge, if we let it in, can radically change the way we live.

But we rarely do. Most of us live in what Heidegger calls “everydayness,” where death is something that happens to other people. We skim the obituary page. We attend the funeral. But we never fully absorb the fact that we’re next. Instead, we flee into distraction, comfort, and consumption.

This is what the author of a recent paper called the “loss of death-to-life reference.” In simpler terms: we’ve lost the thread. Death used to point us back to life, to meaning, to what matters. Now, it’s buried under carnival tents and beer stands at modern funerals, turned into an opportunity to sell trinkets, drown pain, and avoid reflection.

Heidegger believed that to live authentically, we must turn toward our own death—not in morbid fascination, but in honest acknowledgment. He said we should live with death as a “pure possibility,” always present but not yet actualized. It’s not about dwelling on death. It’s about letting it shape the urgency of our days.

And here’s the paradox: when we face death head-on, life sharpens. Viktor Frankl put it well—if we were immortal, nothing would matter. We could postpone everything forever. But because we’re finite, we’re called to act, to love, to create now.

This isn’t a plea for some stoic resignation or heroic denial of grief. Death hurts. The loss of someone we love breaks us. But the pain of death can also become a kind of teacher. It reminds us that life is not just a timeline—it’s a trembling, temporary flame. And the way we treat that flame—our own and others’—reveals everything about who we are.

There’s nothing inherently meaningful about death. But the awareness of it? That’s different. Death awareness can crack open the shell of ego and force us to ask the questions we spend our lives trying to avoid. What matters? What lasts? What have I been avoiding because I thought I had time?

Modern culture isn’t designed to help us answer those questions. It’s designed to numb them. That’s why reclaiming the existential weight of death is not just personal—it’s cultural. It’s spiritual. It’s ethical.

So here’s the real question: What would your life look like if you lived it with the constant awareness that it’s going to end?

Not someday.

Not in theory.

But for real.

Sooner than you think.

That’s not meant to depress you. It’s meant to wake you up.

“Automatic Fantastic,” 30” x 40” (72 x 102cm), acrylic and mixed media on canvas. April 25, 2025 Quinn Jacobson Las Cruces, New Mexico

I really like how the cadmium red dripping down from the left “eye” follows the texture in the painting. This iPhone snap doesn’t do it justice. I hope you get the idea, though.

UPDATE: As I've lived with "Automatic Fantastic" in my living room these past days, I find myself constantly drawn to it, discovering layers I hadn't initially perceived. Perhaps the most significant revelation has been the two cadmium red drips that now unmistakably appear as figures to me - facing each other in what seems like a dance. But not just any dance - they're leaning back from one another, creating this wonderful tension in their posture. I see them now as contemplative beings, suspended in motion while engaged in some weightier communion. They dance, yes, but they also philosophize - their backward arcs suggesting a simultaneous physical and mental reaching. There's something profoundly existential in how they hold space together, as if their movement is both an acknowledgment of mortality and a defiance of it.

Thinking About Doctoral Studies and V.2 Automatic Fantastic

THINKING ABOUT THE DOCTORAL STUDIES PROGRAM

Starting a doctoral program is a strange thing—part intellectual pursuit, part personal reckoning. You don’t just show up to study something interesting; you’re expected to bring something new into the world. The whole premise of a PhD is to explore uncharted terrain—to contribute original thought to a field that matters to you.

That’s not as simple as it sounds. Academia doesn’t reward echo chambers. You need a question that hasn't been fully asked yet, or at least not asked in your way. For me, that means going deeper into what I’ve already spent years wrestling with: mortality, creativity, and the human need to matter in the face of death.

As I write this today, my thesis is rooted in the importance of creativity—not as a luxury, but as a lifeline. Specifically, I’m exploring how artists navigate the awareness of death and the existential tension it creates. What does it mean to make something—anything—while knowing you're impermanent? Does that act of creation actually change anything? Does it soothe, disrupt, clarify? And if it does… how?

These are the questions that pull at me. They’re not abstract. I’ve lived them. I’ve applied these ideas to my own creative process for years, using photography and painting as a way to wrestle with grief, memory, and the inevitability of death. What I’m after now is a deeper understanding—not just for myself, but for others who feel the same pull toward making meaning in a world that guarantees our disappearance.

The doctoral program I’ve joined refers to this early vision as a “vision seed.” I like that. Seeds hold potential. They require care, patience, and the right conditions to grow. My vision seed is simple: I want to ask new questions at the intersection of art, psychology, and philosophy. I want to know what happens when creatives become fully conscious of the existential work their art is doing—when they no longer sublimate unconsciously but engage directly with mortality through the act of making.

If I can shape this into something useful, I hope to produce a thesis that not only contributes to the academic conversation but also encourages a more vital, creative, and psychologically honest way of living. Ideally, this research becomes the foundation for a university course—something like Creativity and Mortality: Confronting the Void Through Art. A course for artists, therapists, and seekers. For anyone brave enough to stop looking away.

Maybe it’s a workshop. Maybe it’s a lecture series. Maybe it's something entirely new—a space where art becomes both expression and inquiry, where mortality isn’t denied but invited into the room. Either way, this is the path I’m on. And for the first time in a long while, it feels like the right one.

AUTOMATIC FANTASTIC V.2

I wasn’t finished with this painting yesterday - I kind of knew that but wanted to think about it. I think this piece perfectly embodies what Becker would call our "immortality project"—the desperate creative act against the void. The black textured background creates this sense of cosmic darkness, the kind we all fear when contemplating non-existence. The twin red-orange circles with their dripping streaks remind me of weeping eyes, like the piece itself is crying out against its own mortality.

The scratched and chaotic surface texture feels like my own anxious mind trying to make order from disorder. Isn't that what we're all doing? Creating meaning through art to ward off death anxiety? The stark contrast between the vibrant orange-red and the textured black background creates this visceral tension - life against death, consciousness against oblivion.

There's something primal here that connects to what Terror Management Theory suggests about our symbolic defenses against mortality. The almost face-like quality emerging from the blackness speaks to me of the self trying to assert itself against nothingness. The dripping paint suggests impermanence, yet the work itself stands as a defiant act of creation.

This piece doesn't just represent death anxiety - it performs it through its very existence. As an artist, I'm not just depicting mortality; I'm actively negotiating with it, creating something that might outlast my physical self. Isn't that what separates artistic creation from other forms of death denial? We don't just distract ourselves from death - we transform our relationship with it.

“Fish & Man” 9” x 12” acrylic on paper and mixed media.

Humans Are Emotional—Not Rational

It shouldn’t be news to tell you that humans are irrational and emotional.

As human beings, we often pride ourselves on being rational creatures. We point to our advancements in science, our mastery of complex tools, and our ability to build societies governed by rules and logic. However, when it comes to matters of life and death, we reveal a different, more primal truth: we are emotional beings. This distinction becomes glaringly apparent when we confront the existential reality of our mortality. Death anxiety and the mechanisms we employ to manage this fear expose the raw emotional underpinnings of human behavior, challenging the veneer of rationality that we so often wear.

At the heart of our emotional nature is the profound discomfort with the knowledge that we will one day cease to exist—impermanence and finitude. Unlike other animals, humans possess a heightened awareness of mortality. This awareness creates a paradox: we have the intellectual capacity to understand our finite nature, but emotionally, we find this knowledge unbearable (Half Animal and Half Symbolic). Ernest Becker, in The Denial of Death, argues that much of human behavior is driven by a need to escape the paralyzing fear of death. This fear is not something we reason through; it is something we feel deeply, viscerally, and often uncontrollably.

Terror Management Theory (TMT) builds on Becker's insights, demonstrating how our emotional responses to death anxiety shape cultural worldviews, self-esteem, and interpersonal behaviors. According to TMT, humans create and cling to cultural systems that provide a sense of meaning, order, and immortality. These systems, whether religious, nationalistic, or ideological, are less about logical coherence and more about emotional comfort. They serve as psychological defenses (coping mechanisms), buffering us against the terror of our inevitable demise.

Consider the way people react when their belief systems are challenged. Rationally, one might expect open-minded discussion or a willingness to adapt to new evidence. Yet, more often than not, such challenges evoke defensiveness, hostility, or even aggression. This is because these belief systems are not merely intellectual constructs; they are emotional lifelines that protect us from existential dread (meaning system buffers). When they are threatened, it feels as though the foundation of our existence is being shaken, triggering a fight-or-flight response that is anything but rational.

This emotional foundation extends beyond our cultural worldviews, or meaning systems, to our personal identities. Self-esteem, for instance, is deeply tied to our ability to stave off death anxiety. TMT research shows that when people are reminded of their mortality, they often seek validation and strive for achievements that affirm their worth within their cultural framework. These actions are not driven by logical analysis but by an emotional need to feel significant in the face of insignificance.

Art and creativity provide another lens through which to examine the emotional nature of human responses to mortality. Artistic expressions, whether through painting, literature, or photography, often grapple with themes of death and immortality. These works resonate not because they offer rational solutions to the problem of mortality but because they evoke and articulate the emotions associated with it. They allow us to confront our fears, find solace, and connect with others who share our struggles.

The emotionality of human beings is perhaps most evident in the collective rituals surrounding death. Funerals, memorials, and acts of remembrance are rarely about logical considerations. Instead, they are about processing grief, celebrating life, and reaffirming our connections to one another and to the cultural narratives that give our lives meaning. These rituals are deeply symbolic, and their power lies in their ability to address emotional needs that logic cannot satisfy.

Acknowledging our emotional nature does not diminish our humanity; rather, it deepens our understanding of it. By recognizing that our responses to death anxiety are rooted in emotion, we can better understand the behaviors, beliefs, and systems that define our lives. This recognition also invites compassion—for ourselves and for others. It reminds us that beneath the facade of rationality, we are all grappling with the same fundamental fears and seeking the same solace in the face of the unknown.

In the end, it is our emotions, not our reason, that drive us to create, to connect, and to seek meaning. Our attempts to manage death anxiety may not always be rational, but they are profoundly human. They reveal our capacity for hope, resilience, and imagination in the face of mortality. And it is through these emotional endeavors that we find not only a way to endure but a way to transcend the limitations of our finite existence.

“Untitled #0924,” 9” x 12” acrylic on paper. September 2024 The Organ Mountains had an influence on these marks and textures. I see them every morning when I go out. You could call this an abstract landscape in that sense. The color is another representation of the desert I live in—the reds, greens, and oranges are all around.

Rituals and Selfies: Creating Shields and Seeking Immortality

A constant stream of thoughts go through my head about human behavior related to death anxiety and the denial of death every day, almost all day—or most of the day.

I would like to think that I am observing, not judging. I’m not sure if that’s true, but I would like to think I’m (mostly) objective.

The things of considerable importance to me are the concepts of epistemology and critical thinking. I like evidence and reason, too. Therefore, when I witness irrational or unreasonable behavior or thinking, it affects me deeply. And I see a lot of it. All of the time.

These streams of thought are usually productive, or at least beneficial, to start a piece of art or to write about. Sometimes, it’s simply connecting the dots and ending up in a feedback loop that I can’t break. Input and output. Output cycled back around as input. Do you get it?

Here’s one that keeps coming back to me most every day—I think writing it out might purge it from my mind.

Ernest Becker said, “I think that underneath everything that is at stake in human life is the problem of the terror of this planet. It is a mystic temple and a hall of doom. If you don’t see it that way, you’ve built defenses against seeing it as it is.“ Wow! That hits me so hard—I mean really, really hard. Every time I read it, it feels like the first time.

What does he mean?

I think this quote reflects his view that at the core of human existence lies a profound awareness of mortality and the terror associated with it. And if you don’t see it that way, you’ve adopted distractions to avoid seeing it as it is. Period. These distractions (I call them illusions of importance) are prolific.

He captures the paradox of life by referring to the world as both a "mystic temple and a hall of doom," where beauty, wonder, and mystery coexist with the certainty of death. This awareness is the source of deep existential anxiety that drives most human behavior.

Most people build psychological defenses—systems of meaning, beliefs, and cultural symbols—to protect themselves from fully experiencing this "hall of doom." They can function without constant existential terror by distancing themselves from the reality of death. However, Becker believed that living authentically means facing this awareness directly, acknowledging both the mystical and the doom-laden aspects of life. It’s a path that not everyone takes because of the fear and vulnerability it demands, but it can lead to a deeper understanding of what it means to be human. And, as a creative person, if you are one.

“I think that underneath everything that is at stake in human life is the problem of the terror of this planet. It is a mystic temple and a hall of doom. If you don’t see it that way, you’ve built defenses against seeing it as it is.”

This idea forms the foundation of The Denial of Death and Escape from Evil (two great books you should read), where Becker explores how our defenses against death influence culture, religion, wars, climate change, and interpersonal conflicts.

Which brings me to my point. One of the ideas I’ve been thinking about is religious rituals (of any flavor) and social media selfies. It sounds like an odd combination, but hear me out.

RELIGIONS, SHOPPING, TV, & DRUGS

First, religious rituals. Religion has been something humans have leaned on to quell existential terror for as long as we have been conscious of our mortality. And most prescribe some kind of ritual or rituals—rules to obey—and are preoccupied with. The “immortality seeking” is strong with religion. Most religions offer some kind of afterlife or immortality. We crave that. Whether it’s symbolic or literal. In the end, we know we are decaying sacks of meat that will die. Psychologically, we can’t handle this—we find ways to deny and lie about it.

In religion, it can be any ritual that’s executed over and over again. I think about Catholic rosary beads, Hindu chanting (Vedic chant), or Orthodox Jews swaying back and forth while praying or reading the Torah; called “shuckling.” The word comes from Yiddish and means "to shake, rock, or swing." Or even praying or meditation for long periods of time. Any of it can be a sign of extreme existential struggles (all happening outside of consciousness).

Organ Mountains - Las Cruces, New Mexico

That kind of constant diversion or distraction is, to me, a sign of palpable death anxiety. To occupy your mind so completely and fully is a sure sign that we want to avoid the thought of death at all costs. The non-religious do it for shorter periods of time, things like movies, shopping, sporting games, and music concerts. Anything that transports you away from the mortal coil and thoughts of dying.

Drugs are a very common way to escape reality too. It’s interesting we use the term “escape reality.” What does that mean? Reality equals “I’m going to die.” After all, the human mortality rate is 100%. Drugs can lead to some pretty bad endings, so not a good choice to use as a buffer. I might argue that with shopping and other activities we use to distract ourselves from “reality.”

SOCIAL MEDIA SELFIES

Social media selfies. I have struggled with this for a long time. I’m amazed at the number of people whose feed is almost nothing but selfies. My first thought is malignant narcissism. However, that's just a fraction of it. To see older people curating their lives and making sure they “look good” for the photo is so obvious to me—it’s like I’m seeing the Dunning-Kruger effect of visual information. In the end, I’m sad about it. I feel sorry for the people. The phoniness, the construction of a life they DO NOT have, and the looks they DO NOT possess (our culture craves youth and fitness—immortality). The fear of death—the fear of growing older and closer to death—is real. And it shows.

I recently read an article in the Daily Mail (British Paper) about a study done in Israel. It said,

“Many of us have phones filled with selfies documenting everything from holidays to duvet days. But what's behind the modern fascination with taking photos of ourselves? Psychologists have come up with a rather morbid answer: fear of dying. Researchers from Tel Aviv University in Israel quizzed 100 students on the motivations behind their selfie-taking. They found that those who took the most had strong signs of death anxiety, an intense fear of dying that affects up to a fifth of Britons. The experts said they think endless selfie-taking may actually be an attempt to 'preserve a fake feeling of immortality'. In a paper published in the journal Psychological Reports, they wrote, Selfies possibly fulfil a need to remain immortal. One of the behaviours used to achieve feelings of immortality is photography, and nowadays photography is literally on the tip of our fingers.”

I’m sure what they mean by “remain” immortal is looking youthful and good. The idea is that by taking pictures of yourself, you find psychological security in “preserving” yourself forever. They went on to say, “We found the more people were aware (and afraid) of their death, the more they were taking and sharing selfies. Other studies have suggested that people spend an average of seven minutes a day grinning into smartphone cameras for the perfect snap to post on social media.”

So the next time you see a social media account with endless selfies, or even a lot of them, remember that existential struggles are real for people. Moreover, think about how you cope with your knowledge of mortality. You have something you use, or many things; what are they? Are you aware? Or does this happen without your conscious acknowledgment?

The Studio Q Show LIVE! September 4, 2024 at 1700 MST

Join Quinn on Wednesday evening (September 4, 2024, at 1700 MST) for a talk with Dr. Sheldon Solomon, author of The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life. Quinn and Sheldon will talk about how artists differ in their response to death anxiety. What can an artist do to harness this powerful psychological phenomenon? Can the knowledge of our impending deaths make us more creative?

The Studio Q Show LIVE! July 27, 2024 at 1000 MST Part 3

THE CREATIVE ANIMAL??

This week, Quinn will continue the series on The Creative Mind and Mortality, Part 3."This will address artist's unique perspectives on why they create art and the struggles they face in light of existential dread or mortality.

What does it mean to have a "creative practice"?

How does creating art help with the fear of death?

Do creative people process existential terror differently? If so, how?

Ernest Becker's "The Denial of Death" and Otto Rank's book "Art and Artist."

Stream Yard (LIVE): https://streamyard.com/jc28hrjyd2

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/live/VeLDm2Xv2K0?si=nUy1SRxfR75J481P