Leaving a trace—the mark of a white-winged dove on my kitchen window. December 28, 2025

A white-winged dove hits the glass, and what’s left behind isn’t the bird but the residue of contact: a powdery bloom, two wing smears, and a ghosted body shape suspended in light. That’s the interview in miniature. Dr. Fisher and I are circling the same problem from different angles: how the most real forces in a human life rarely show up directly. They show up as traces. As misreadings. As displaced language. As the “dimmer switch” doing its job.

I’m interested in what the awareness of an ending does to the living, minute by minute. The dove doesn’t leave a story; it leaves evidence. A mark that asks to be interpreted. It’s rupture without a sermon: meaning fails for a second, the world stutters, and then you’re standing there in your own kitchen looking at a fragile imprint and feeling the entire question come back online.

Interview With Dr. R. Michael Fisher: Careers of Folly and Wisdom

In this conversation, I sit down with Dr. R. Michael Fisher for Careers of Folly and Wisdom (Episode 3) at the close of 2025, and we trace the strange overlap between two lives shaped by study, teaching, and the long arc of existential pressure. What begins as a simple introduction quickly becomes a deeper exchange about why some ideas take decades to name and why the hardest work is often learning how to speak those ideas in public without having them reduced to something smaller.

We talk about how we connected through Southwestern College’s Visionary Practice & Regenerative Leadership doctoral program and why I went searching for faculty whose work could actually hold what I’m building: an arts-based inquiry into creativity, mortality, and the psychological machinery of denial. I share my early “folly” at residency, where I became “the death guy” despite my real focus being the opposite: what happens inside the dash between birth and death, and how the knowledge of impermanence reshapes a human life. That misreading became a kind of field experiment in real time, revealing how quickly people reroute mortality talk into safer channels like grief, loss, or therapeutic language. It also forced me to sharpen my communication, not by diluting the thesis, but by learning how to meet the audience where the “dimmer switch” is already working.

From there, the conversation widens. Dr. Fisher pushes on the themes of education, fallibility, and maturity: how a person with deep content and lived experience learns to teach without preaching, and how humility becomes an actual method. I bring in two foundational touchstones that anchor my work: Becker’s insistence that death terror is a mainspring of human activity and Rank’s claim (via Becker) that the artist takes in the world and reworks it rather than being crushed by it. That tension is the engine of my research question: if most of culture is organized to keep death out of view, what do artists do differently with that same pressure, consciously or unconsciously?

A major thread running through the interview is that denial is not just a personal quirk. It’s cultural, political, and historical. I talk about early experiences that formed my worldview, including family stories that complicate simple narratives of “normal” American life, and how those early exposures shaped my sensitivity to power, erasure, and the stories nations tell themselves. We also move into my military background, where I describe the kind of learning you don’t go looking for: the collision between youthful exceptionalism and the realities of violence, trauma, and institutional harm, including witnessing suicide deaths while working as a photographer. The folly, as I name it, is the arrogance of certainty; the wisdom is the painful clarity that comes after the myth breaks.

In the final stretch, we pivot to Dr. Fisher’s work in fearology and his reframing of Terror Management Theory as, in many ways, a kind of “fear management education.” That exchange matters because it shows the real stakes of language: fear, terror, anxiety, and denial. These aren’t interchangeable terms, and both of us have been forced to grapple with how quickly audiences collapse complex ideas into familiar clichés. We end with a concise statement of my own working thesis, offered almost like a poem: artists tend to give anxiety form rather than discharge it through denial; material practice slows experience enough for mortality to move into objects; rupture is where meaning fails, and art often happens there; the ethic is not to “fix” the break, but to stay present with it.

The conversation closes on an honest note about the cost of passion. We talk about parenting, devotion to work, and the ways even meaningful lives leave blind spots in their wake. If this episode has a through-line, it’s that wisdom is rarely clean. It comes out of misfires, misreadings, and the slow work of learning how to hold the real without turning it into a brand, a sermon, or a therapy session.

I really enjoyed the conversation, and I look forward to working with Dr. Fisher. Check out his YouTube channel and his other interviews and commentary.

Racism isn’t innate – Here are Five Psychological Stages that may Lead to It

I encourage you to take a look at this article from The Conversation. It references Terror Management Theory, which to me is one of the most overlooked—and ignored—frameworks for understanding the problems we face today.

From racism to war, from bigotry and xenophobia to jingoism and religious dogma, we seem almost determined to find “the other.” As the old saying goes, I’ll hate you for the color of your shirt or the shape of your nose. Anything will do, so long as it puts someone in the “out group.” America has been marinating in this for a long time, and at this moment, I don’t see the future looking particularly bright. If anything, I’d caution people to prepare themselves for more, and larger, terrible events ahead.

You can already see it unfolding: Russia’s war in Ukraine, the genocide in Gaza, and climate disasters that grow more relentless each year—wildfires, hurricanes, and flooding. These events are not only catastrophic in themselves, but they remind us, again and again, of our own fragility and mortality. And when we are forced to face that, death anxiety tends to boil over into hostility, scapegoating, and division.

“We spend endless energy on the ‘what’ of our problems but rarely ask the ‘why.’ It’s like treating a cough while ignoring the virus that causes it.”

Add to this the terrible political divide in America: the Kirk assassination, Trump sending troops into American cities, and the daily drumbeat of culture war rhetoric. Political party loyalties—red and blue alike—are tearing at the fabric of our society. Even in our everyday lives, people seem more standoffish, impatient, and cold (I’ve felt this for a few years). It’s as if the collective weight of death anxiety is bubbling up everywhere, pushing us further into our corners.

This is what my studies and interests revolve around: what the fear of non-existence means for people and how it runs outside of conscious awareness. Terror Management Theory and Ernest Becker’s work hold so much explanatory power, I can’t understand why more people don’t embrace them—don’t bring them into their lives. Our world would be a much better place if we did.

Sheldon Solomon, building on Becker, put it bluntly: We will always need a designated group of inferiors.

What do you think? Do you see this drive to divide and “other” playing out in your own circles, communities, or even in the way strangers treat each other on the street? I’d love to hear your perspective.

And yet, I can’t help but believe there’s another path. If we had the courage to face death honestly, maybe we wouldn’t need enemies at all.

A Conversation I've Had Many Times

Them: “Quinn, what are you talking about? I don’t think about death. I’m not afraid of it.”

You: That’s a bold claim. But let me ask—what do you think happens when you die?

Them: I don’t know. I guess nothing. You just stop existing.

You: And imagining that—your body gone, your projects unfinished, your name forgotten, your consciousness erased—doesn’t stir anything in you? No unease at all?

Them: Not really. I don’t think so.

You: That’s fascinating, because Becker would say that’s exactly how denial works. The fear doesn’t disappear—it sinks below awareness. And then culture steps in with buffers: religion, family, nation, career, personal projects, lifestyle, and even the idea that progress or legacy will carry you forward. You’re protected from having to feel the dread directly.

Them: Maybe. But I still don’t feel afraid.

You: And yet you live inside projects of meaning every day—your work, your relationships, the things you deeply care about, and your hopes for the future. Why do those matter if death doesn’t? Becker would say they matter because of death—because without them, the nothingness is unbearable. So I must question: does your confidence truly embody fearlessness, or is it the most potent form of denial—one so subtle that it remains invisible to you?

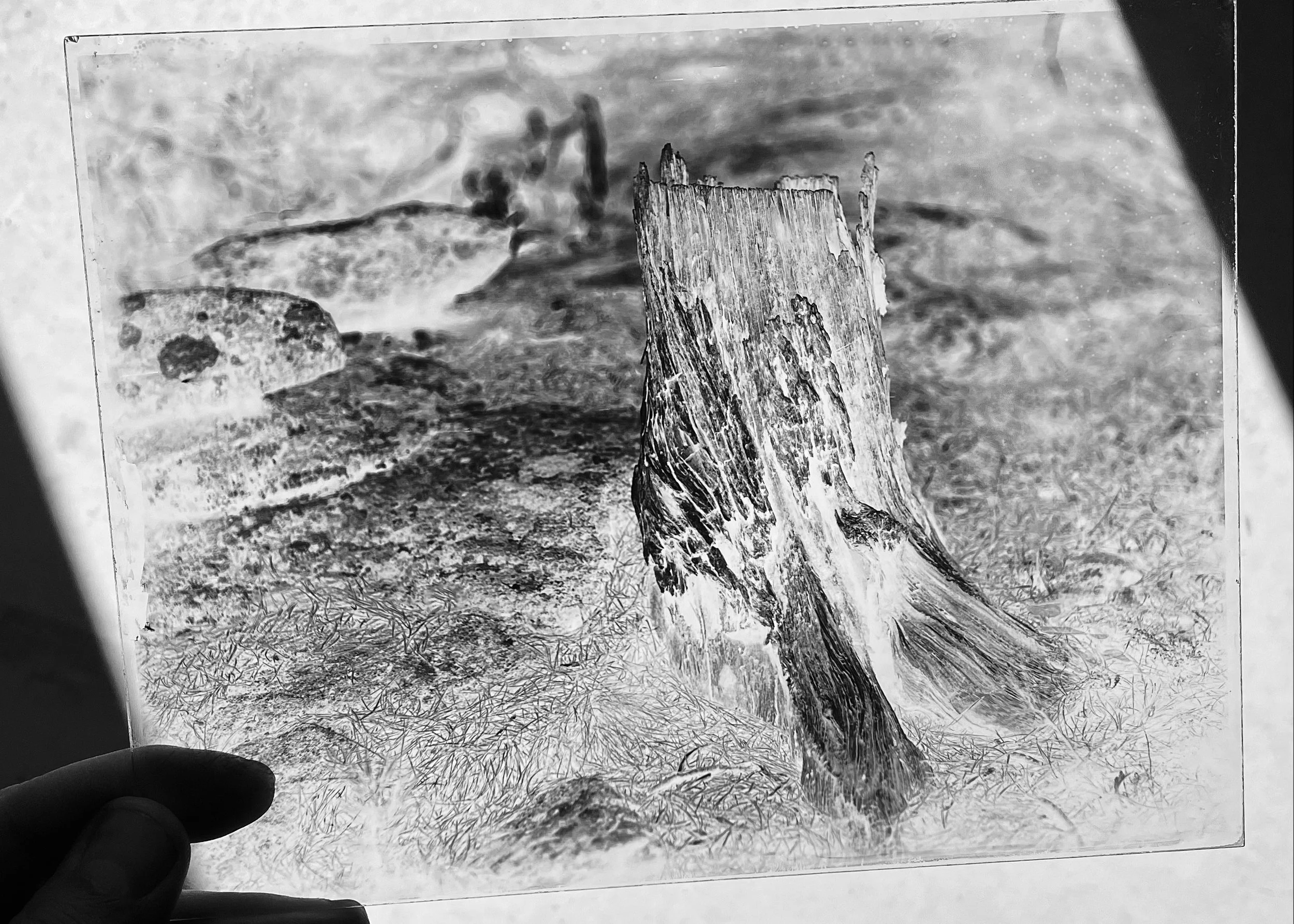

A whole plate wet collodion negative held against a light table to inspect for density.

Photography Was Born from Death Anxiety

In Flashes of Brilliance, Anika Burgess maps the birth of photography across the 19th century—a strange, luminous era where light first learned how to remember. But underneath the surface of these technical milestones is something deeper: the same existential terror Ernest Becker exposed in The Denial of Death. Photography, from the beginning, was a defense against our disappearance.

The daguerreotype, introduced by Louis Daguerre in 1839, wasn’t just a new technology—it was a cultural event. Suddenly, faces could outlive their flesh. Sitting for a portrait was serious business. You had to be still for minutes, sometimes longer, and the result was a haunted likeness, sealed in silver and glass. It was more than documentation—it was a bid for immortality. Becker might say it was a way to manage death anxiety by creating a symbolic self that could outlast the body.

Before Daguerre, Nicéphore Niépce spent years coaxing ghostly images from bitumen and sunlight. His exposures took days. His results were vague, barely-there impressions—like memory itself. Still, he was trying to do what we all do: leave a trace.

The real turning point came with Frederick Scott Archer’s wet collodion process in 1851. It was faster, sharper, and allowed for duplication. Suddenly, your image could exist in multiple places at once. You didn’t just resist death—you replicated yourself. The carte de visite, popularized shortly after, took this further. You could hand out tiny portraits like tokens of your existence, proof that you’d been here, that you mattered.

And it wasn’t just about faces. Flash powder brought violent light into dark rooms, revealing what the eye couldn’t see. Solar enlargers, early color processes, even underwater photography—all pushed the boundaries of time and space. Burgess notes that many photographers were driven by obsession, risk, even self-destruction. They were intoxicated by the possibility of preservation. Isn’t that what Becker called the “immortality project”? Whether through fame, art, religion, or science—we’re always trying to escape the void.

Photography, in its early years, was dangerous (read Bill Jay’s “Dangers in the Dark”). Mercury, ether, explosive chemicals. But what else would we expect from a practice rooted in anxiety? It was an alchemy fueled by fear and longing. It gave people the illusion of permanence, even as everything around them was vanishing.

Burgess’s book isn’t just a history—it’s a reminder that every photograph is a symptom of our condition. It’s a way to say: I was here. I saw. I mattered.

As someone who works with 19th-century processes today, I feel that tension every time I pour collodion or pull a plate from the fixer. The medium has always been about death. About holding onto something just long enough to believe we’re not already disappearing.

And maybe that’s the brilliance Burgess is talking about. Not just in the chemical spark of silver meeting light—but in the way humans, terrified of their own impermanence, invented a machine to freeze time.

The Sycamore Gap tree was cut down in September 2023. SunCity/Shutterstock

How The Sycamore Gap Tree Stirred Emotions

I read an article from The Conversation yesterday about the felling of a sycamore tree in Britain. It was a tree that stood in a dip along Hadrian’s Wall. I encourage you to read it (link here).

Here are my thoughts.

When the Sycamore Gap tree was felled, people mourned it as if it were a living companion. On the surface, it was just a tree—an old, striking landmark framed by the British landscape. But for so many, it was an emotional anchor, the kind of place our minds use to orient us in the world. Psychology tells us that our brains don’t separate memory, emotion, and place as cleanly as we like to think. They’re tangled together, just like the roots of that sycamore.

Ernest Becker would have recognized the deeper undercurrent here. We’re always looking for ways to transcend our finitude—some symbolic form of permanence that outlasts us. A tree like Sycamore Gap becomes part of a cultural worldview, an immortal marker on our mental maps. When it’s destroyed, it cracks that illusion. People felt disoriented, even betrayed. It wasn’t just the loss of scenery—it was a reminder that nothing is safe from time’s reach.

In my own work, I circle this idea constantly: that our fear of death fuels our attachments, our art, our need for landmarks—literal and symbolic. We pin our anxieties onto places, trees, myths, hoping they’ll hold steady where we can’t. The Sycamore Gap tree stood alone on that ridge for centuries, and for a moment, it made us feel we could stand a little taller, too. Its absence leaves us staring straight at our own impermanence. That, perhaps, is why we grieve it so fiercely.

We Will Be Forgotten

We Die. Then We’re Forgotten.

We all know life ends. That’s not the surprise. The harder part is this: not only do we die, but we’re eventually forgotten. Completely. That fact sits at the edge of consciousness—rarely invited in, but always looming.

A year ago, I saw this video about Danish photographer Balder Olrik. It just resurfaced in my YouTube feed. An artist, going through a health crisis, came face-to-face with his mortality. It shook him. He realized, maybe for the first time, that he’s going to die. And not just die, but vanish from memory. No legacy. No monument. Just absence.

It hit me because I see this all the time: artists wrestling with death anxiety without having the language to name it. They circle around it, feeling it, expressing it, but never quite framing it. This is exactly the moment where Ernest Becker’s work becomes powerful. If I could talk to this guy, I’d walk him through Becker’s ideas—the tension between our symbolic hunger and our fragile biology. I think it would land. I think it would help.

What’s most interesting is this: in the midst of his anxiety, he’s creating. That’s the paradox. He’s using the very thing that can help him confront death—artmaking—without realizing it. Creativity isn’t a cure, but it is a confrontation. It’s a way to say: I know I’m going to die… but here’s what I made while I was here.

Spend 16 minutes and watch it. You won’t regret it.

“Army Targets (Uncle Sam in the Fog of War),” acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 2025 (detail from the larger 30” x 40” canvas)

A Question To Contemplate

Question: What if we didn't know we were going to die?

I've been wrestling with this question for a while now. I’m sitting in my studio surrounded by my large-format cameras, lenses, and half-finished canvases, drawings, and pieces of ideas, feeling the persistent hum of mortality that seems to drive every mark I make and every plate I expose.

Becker wrote about our knowledge of death as the fundamental human condition—the thing that separates us from every other creature on this planet. But what if that knowledge simply wasn't there? Like your dog sprawled in the afternoon sun, or your cat stalking a shadow, or a lion moving through the African grasslands. They have no concept that they're finite beings. All they know is the immediate drive to survive and reproduce (and we have that too).

Imagine it. Really imagine it. You wake up tomorrow with no concept that your body will one day stop working, that your consciousness will end, that there's a finite number of sunrises ahead of you. How would you move through the world? What would the world look like?

I think about my own creative practice, how much of it is driven by the need to leave something behind to create meaning in the face of the void. Would I still feel that urgent pull to the canvas and the darkroom if death weren't whispering over my shoulder? Would any of us create anything at all?

Consider this: Would we still build monuments? The pyramids exist because pharaohs knew they would die and wanted to transcend that fate. Would we have cathedrals, symphonies, novels—these desperate attempts to touch immortality through art? Or would we live in a world of immediate gratification, where nothing needed to outlast us because we couldn't conceive of not lasting?

Think about love, too. So much of our romantic intensity comes from knowing our time together is limited. "Till death do us part" only has meaning because we understand death exists. Would we love as fiercely if we believed we had infinite time with someone? Would we love at all, or would relationships become casual arrangements since there'd be no urgency, no preciousness born from scarcity?

What about progress? Every scientific breakthrough, every medical advance, every technological leap forward—aren't these all responses to our limitations, including our ultimate limitation of mortality? We cure diseases because we fear death. We explore space because we dream of transcending our earthly expiration date. We pass knowledge to our children because we know we won't be here forever to guide them.

Without death consciousness, would we become a species of eternal children, living only in the present moment like animals do? There'd be no anxiety about wasting time because we wouldn't understand that time could be wasted. No existential dread, no midnight terrors, no desperate searches for meaning. But also no urgency, no drive to become more than we are.

I keep coming back to this in my work. Every painting I create carries within it the knowledge that both the artist and the viewer will someday be gone. That tension between permanence and impermanence—it's what gives art its power. Strip away death awareness, and do we lose the very thing that makes us human?

But here's what really haunts me: Would we be happier? Becker argued that our knowledge of death creates neurosis, depression, and the endless search for ways to deny our mortality through heroism and meaning-making. Without that knowledge, would we live in a state of pure being, untroubled by the existential weight that crushes so many of us?

Or would something else emerge to fill that void? Some other awareness, some other source of meaning and motivation that we can't even imagine because death looms so large in our current consciousness?

I want to hear from you. Sit with this question for a moment. Let it unsettle you the way it's unsettled me.

What do you think would change? What would we lose? What might we gain?

Would art exist without death anxiety driving it? Would you have the same intensity? Would we still reach for the stars, or would we be content to never leave the ground?

Share your thoughts. Challenge my assumptions. Push this question further than I have. Because if there's one thing I've learned in exploring these ideas, it's that the most profound questions are meant to be wrestled with together, not solved in isolation.

What would we become if we didn't know we were going to die?

“Ice Fish,” 9” x 12” acrylic on paper.

The title, "Ice Fish," evokes a creature navigating a hostile, frozen environment, which can be read as a metaphor for the human condition: a delicate being striving to survive and find purpose in a world fraught with existential threats. The ice itself, often associated with stasis or preservation, could symbolize the human desire to "freeze" or immortalize moments of life—an act that speaks to our efforts to transcend impermanence through art, culture, and memory.

"Ice Fish" captures the psychological landscape of death anxiety, presenting viewers with a visual meditation on how we confront and manage the tension between life's fragility and our yearning for meaning and permanence. It becomes not just a painting but an existential narrative—a reminder of both our vulnerability and our resilience in the shadow of mortality.

Denial: Self-Deception, False Beliefs, and the Origins of the Human Mind

Denial: Self-Deception, False Beliefs, and the Origins of the Human Mind by Ajit Varki and Danny Brower

Happy 2025! I hope this year is a good year for you.

A couple of years ago, I read a book called Denial: Self-Deception, False Beliefs, and the Origins of the Human Mind, by Ajit Varki and Danny Brower. I’ve written about it before here. It played an important role in my studies. It deals with our evolutionary psychology. Evolutionary psychology is something rarely considered when thinking about why we are the way we are. This book gives some very interesting and plausible explanations for our behavior.

They propose a provocative hypothesis that marries the Theory of Mind (TOM) with Mortality Awareness through the Mind Over Reality Transition (MORT) to explain one of humanity’s most perplexing characteristics: the denial of death. Their central argument is rooted in the paradox that human beings, uniquely aware of their own mortality, have also evolved mechanisms to suppress the existential terror this awareness entails. This duality, they argue, is a key to understanding not just human psychology but also the evolutionary processes that shaped our species.

The Evolutionary Conundrum of Awareness and Denial

Human beings possess an extraordinary ability to recognize that others have minds—a skill encompassed in the Theory of Mind. This capacity enables us to infer the intentions, beliefs, and emotions of others, facilitating complex social interactions and cooperation. However, TOM is not merely an interpersonal tool; it also turns inward, allowing us to imagine our future selves. This introspective ability inevitably leads to the realization of our own mortality. An organism's realization that it will eventually die marks both an evolutionary milestone and a potential psychological roadblock.

Varki and Brower posit that this acute awareness of mortality could have been paralyzing. A creature consumed by the fear of its own inevitable demise might struggle to survive, let alone reproduce. Natural selection, however, provided a solution: the cognitive ability to deny uncomfortable truths. This capacity for self-deception—what Varki and Brower term the "Mind Over Reality Transition" (MORT)—allowed early humans to sidestep the crippling anxiety of mortality while retaining the evolutionary advantages of self-awareness and social cognition.

Denial as a Survival Mechanism

The denial of death operates as an adaptive mechanism that balances the benefits of self-awareness against its existential costs. This balance is crucial. Without an understanding of mortality, humans would lack the foresight and caution necessary to avoid life-threatening dangers. But without denial, the dread of death could lead to apathy, despair, or an inability to take risks—all of which would hinder survival and reproductive success.

This interplay between TOM and MORT reveals an elegant evolutionary solution: our minds are hardwired to accept a paradoxical truth. We know, intellectually, that we are mortal, but we also possess the psychological mechanisms to compartmentalize, suppress, or distort this knowledge. This is not a flaw, but a feature that allows us to concentrate on the tasks of life—building relationships, raising children, creating art, and seeking meaning—without succumbing to the overwhelming presence of death.

The Role of Culture and Terror Management

While evolution provided the foundation for denying death, culture built the scaffolding. Varki and Brower’s ideas resonate strongly with Terror Management Theory (TMT), which suggests that cultural worldviews and symbolic systems are human constructs designed to mitigate death anxiety. Religion, art, philosophy, and even societal norms function as buffers against the existential terror of mortality. They provide frameworks that promise continuity—whether through an afterlife, a legacy, or the enduring influence of one’s creations.

“Existential Dread #9,” 9” x 12” acrylic and charcoal on paper.

This painting serves as a visual exploration of the TOM-MORT hypothesis. The abstraction invites viewers to project their fears and hopes, echoing the way denial itself operates. By obscuring the harsh edges of reality, the mind creates space for connection, creativity, and meaning. Yet, the tension in the painting suggests that denial is not absolute; the void beneath remains visible, demanding contemplation.

It’s both a personal and universal expression of the struggle with mortality. It asks us to confront the void while acknowledging the evolutionary and cultural scaffolding that has allowed us to thrive in its shadow. This piece does not offer resolution but instead invites the viewer into the complex interplay of awareness, denial, and the human condition—a visual testament to the insights into the mind’s delicate dance with reality.

These cultural constructs do more than soothe individual fears; they reinforce social cohesion. Shared beliefs about life and death foster unity, enabling groups to work together toward common goals. In this sense, denial of death is not merely a personal defense mechanism but a social glue that holds communities together.

Implications for Understanding Human Behavior

The TOM-MORT hypothesis invites us to reconsider many aspects of human behavior through the lens of denial. It explains why humans are uniquely capable of both profound creativity and devastating self-destruction. Our ability to deny death enables us to take risks, innovate, and envision futures that might never come to pass. But it also blinds us to long-term consequences, fueling behaviors that threaten our survival, such as environmental degradation and warfare.

Understanding the evolutionary roots of death denial also sheds light on the psychological struggles of modern life. In a world where traditional cultural buffers are eroding, individuals are increasingly confronted with unmediated mortality awareness. The resulting anxiety manifests in various ways, from existential despair to compulsive consumption. Yet, the same cognitive flexibility that enables denial also holds the potential for growth. By confronting the void and integrating our awareness of mortality into our lives, we can find new ways to navigate the human condition.

Varki and Brower’s TOM-MORT hypothesis offers a profound insight into the evolutionary origins of death denial. It reminds us that our ability to deny uncomfortable truths is not a weakness but a survival strategy—one that has allowed us to thrive in the face of existential uncertainty. At the same time, it challenges us to recognize the limitations of this denial. In a world where our actions increasingly have global and long-term consequences, the time may have come to reconcile our evolutionary heritage with the demands of modern existence. Only by understanding the roots of our denial can we hope to transcend it, transforming the fear of death into a catalyst for living fully and responsibly.

“Fish & Man” 9” x 12” acrylic on paper and mixed media.

Humans Are Emotional—Not Rational

It shouldn’t be news to tell you that humans are irrational and emotional.

As human beings, we often pride ourselves on being rational creatures. We point to our advancements in science, our mastery of complex tools, and our ability to build societies governed by rules and logic. However, when it comes to matters of life and death, we reveal a different, more primal truth: we are emotional beings. This distinction becomes glaringly apparent when we confront the existential reality of our mortality. Death anxiety and the mechanisms we employ to manage this fear expose the raw emotional underpinnings of human behavior, challenging the veneer of rationality that we so often wear.

At the heart of our emotional nature is the profound discomfort with the knowledge that we will one day cease to exist—impermanence and finitude. Unlike other animals, humans possess a heightened awareness of mortality. This awareness creates a paradox: we have the intellectual capacity to understand our finite nature, but emotionally, we find this knowledge unbearable (Half Animal and Half Symbolic). Ernest Becker, in The Denial of Death, argues that much of human behavior is driven by a need to escape the paralyzing fear of death. This fear is not something we reason through; it is something we feel deeply, viscerally, and often uncontrollably.

Terror Management Theory (TMT) builds on Becker's insights, demonstrating how our emotional responses to death anxiety shape cultural worldviews, self-esteem, and interpersonal behaviors. According to TMT, humans create and cling to cultural systems that provide a sense of meaning, order, and immortality. These systems, whether religious, nationalistic, or ideological, are less about logical coherence and more about emotional comfort. They serve as psychological defenses (coping mechanisms), buffering us against the terror of our inevitable demise.

Consider the way people react when their belief systems are challenged. Rationally, one might expect open-minded discussion or a willingness to adapt to new evidence. Yet, more often than not, such challenges evoke defensiveness, hostility, or even aggression. This is because these belief systems are not merely intellectual constructs; they are emotional lifelines that protect us from existential dread (meaning system buffers). When they are threatened, it feels as though the foundation of our existence is being shaken, triggering a fight-or-flight response that is anything but rational.

This emotional foundation extends beyond our cultural worldviews, or meaning systems, to our personal identities. Self-esteem, for instance, is deeply tied to our ability to stave off death anxiety. TMT research shows that when people are reminded of their mortality, they often seek validation and strive for achievements that affirm their worth within their cultural framework. These actions are not driven by logical analysis but by an emotional need to feel significant in the face of insignificance.

Art and creativity provide another lens through which to examine the emotional nature of human responses to mortality. Artistic expressions, whether through painting, literature, or photography, often grapple with themes of death and immortality. These works resonate not because they offer rational solutions to the problem of mortality but because they evoke and articulate the emotions associated with it. They allow us to confront our fears, find solace, and connect with others who share our struggles.

The emotionality of human beings is perhaps most evident in the collective rituals surrounding death. Funerals, memorials, and acts of remembrance are rarely about logical considerations. Instead, they are about processing grief, celebrating life, and reaffirming our connections to one another and to the cultural narratives that give our lives meaning. These rituals are deeply symbolic, and their power lies in their ability to address emotional needs that logic cannot satisfy.

Acknowledging our emotional nature does not diminish our humanity; rather, it deepens our understanding of it. By recognizing that our responses to death anxiety are rooted in emotion, we can better understand the behaviors, beliefs, and systems that define our lives. This recognition also invites compassion—for ourselves and for others. It reminds us that beneath the facade of rationality, we are all grappling with the same fundamental fears and seeking the same solace in the face of the unknown.

In the end, it is our emotions, not our reason, that drive us to create, to connect, and to seek meaning. Our attempts to manage death anxiety may not always be rational, but they are profoundly human. They reveal our capacity for hope, resilience, and imagination in the face of mortality. And it is through these emotional endeavors that we find not only a way to endure but a way to transcend the limitations of our finite existence.