In Flashes of Brilliance, Anika Burgess maps the birth of photography across the 19th century—a strange, luminous era where light first learned how to remember. But underneath the surface of these technical milestones is something deeper: the same existential terror Ernest Becker exposed in The Denial of Death. Photography, from the beginning, was a defense against our disappearance.

The daguerreotype, introduced by Louis Daguerre in 1839, wasn’t just a new technology—it was a cultural event. Suddenly, faces could outlive their flesh. Sitting for a portrait was serious business. You had to be still for minutes, sometimes longer, and the result was a haunted likeness, sealed in silver and glass. It was more than documentation—it was a bid for immortality. Becker might say it was a way to manage death anxiety by creating a symbolic self that could outlast the body.

Before Daguerre, Nicéphore Niépce spent years coaxing ghostly images from bitumen and sunlight. His exposures took days. His results were vague, barely-there impressions—like memory itself. Still, he was trying to do what we all do: leave a trace.

The real turning point came with Frederick Scott Archer’s wet collodion process in 1851. It was faster, sharper, and allowed for duplication. Suddenly, your image could exist in multiple places at once. You didn’t just resist death—you replicated yourself. The carte de visite, popularized shortly after, took this further. You could hand out tiny portraits like tokens of your existence, proof that you’d been here, that you mattered.

And it wasn’t just about faces. Flash powder brought violent light into dark rooms, revealing what the eye couldn’t see. Solar enlargers, early color processes, even underwater photography—all pushed the boundaries of time and space. Burgess notes that many photographers were driven by obsession, risk, even self-destruction. They were intoxicated by the possibility of preservation. Isn’t that what Becker called the “immortality project”? Whether through fame, art, religion, or science—we’re always trying to escape the void.

Photography, in its early years, was dangerous (read Bill Jay’s “Dangers in the Dark”). Mercury, ether, explosive chemicals. But what else would we expect from a practice rooted in anxiety? It was an alchemy fueled by fear and longing. It gave people the illusion of permanence, even as everything around them was vanishing.

Burgess’s book isn’t just a history—it’s a reminder that every photograph is a symptom of our condition. It’s a way to say: I was here. I saw. I mattered.

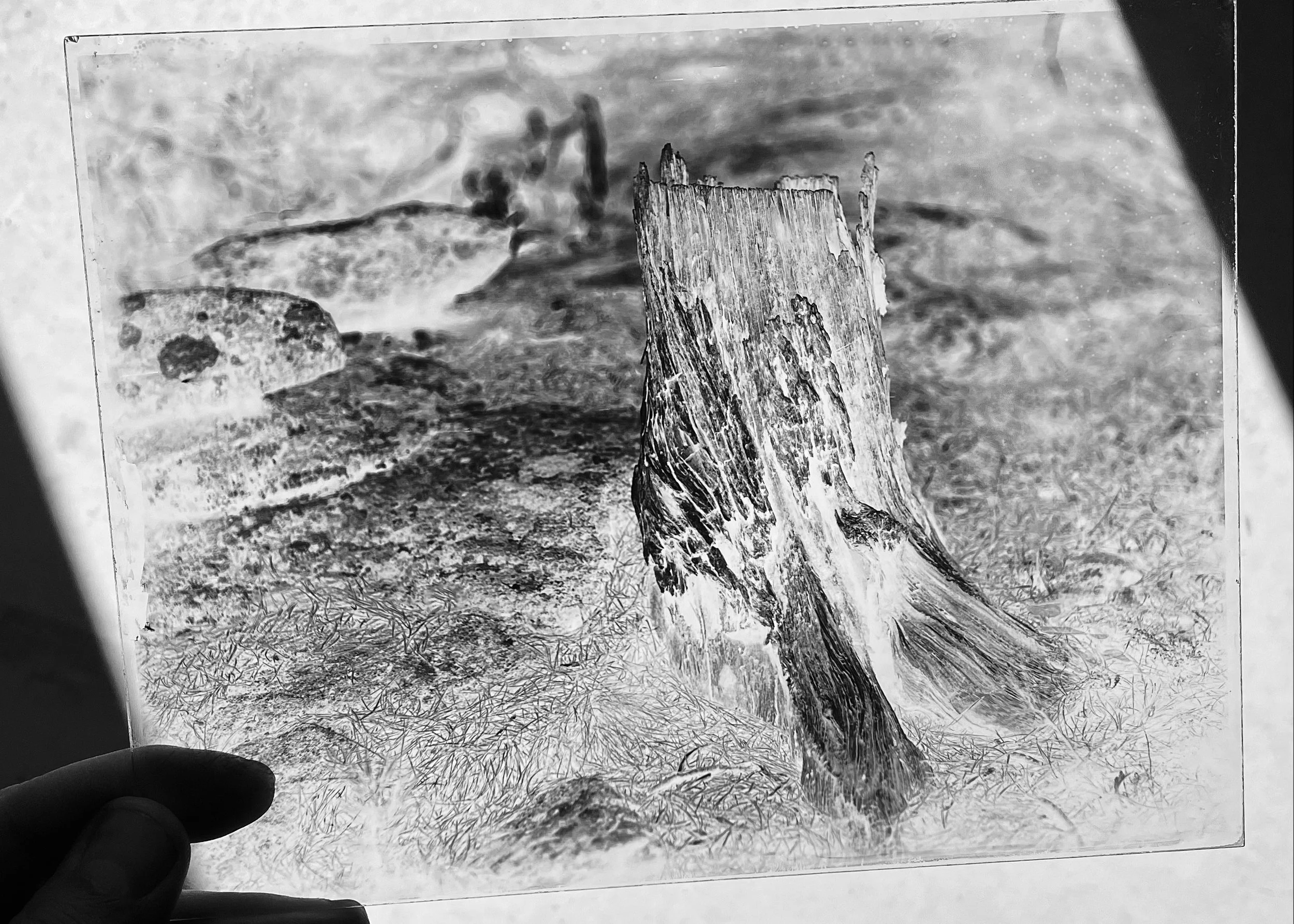

As someone who works with 19th-century processes today, I feel that tension every time I pour collodion or pull a plate from the fixer. The medium has always been about death. About holding onto something just long enough to believe we’re not already disappearing.

And maybe that’s the brilliance Burgess is talking about. Not just in the chemical spark of silver meeting light—but in the way humans, terrified of their own impermanence, invented a machine to freeze time.