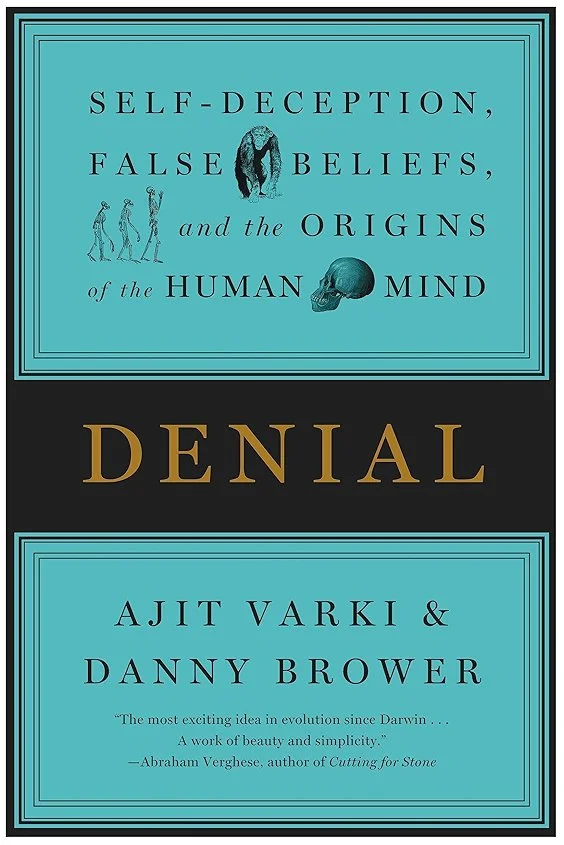

“An organism that fully comprehends the inevitability of its own death should be at a severe evolutionary disadvantage.”

Ajit Varki & Danny Brower

Denial: Self-Deception, False Beliefs, and the Origins of the Human Mind

I want to start by saying why Varki and Brower’s work matters so much to me and why it landed with such force when I first encountered it.

When I talk about their theory, I’m really talking about anthropogeny (an-thro-poge-nee). Not anthropogeny as a list of fossils, dates, or branching diagrams, but anthropogeny as a psychological crossing.

A moment when a creature stops merely responding to the world and begins to recognize itself inside it. When experience turns inward. When danger stops being episodic and becomes existential. When the mind realizes that every threat ends the same way.

Most stories we tell about human evolution focus on our successes. Intelligence. Language. Cooperation. Ingenuity. All of that is real, and all of it matters. But those stories usually glide past a more disturbing question: what happens when a creature becomes capable of knowing that it will die?

If mortality is taken seriously as a psychological event, not just a biological fact, then becoming human is not a clean victory.

It’s a rupture.

Awareness overshoots what an organism should be able to tolerate. Varki and Brower approach this problem not as philosophers or poets, but as biologists asking a brutally simple question: how did a species survive once it could clearly comprehend its own annihilation?

Their answer is denial.

Not denial as ignorance. Not denial as constant delusion. But denial as an evolved capacity. A way of softening reality just enough to stay functional.

In their view, human consciousness did not emerge cleanly at all. It arrived with a built-in workaround. A mechanism that allows unbearable truths to be known without being allowed to dominate awareness completely.

They call this moment the Mind Over Reality Transition, or M.O.R.T. It names the point in human evolution when the mind became powerful enough to override raw perception in order to stay alive.

Before this transition, animals respond directly to reality.

Danger appears, the body reacts.

Hunger arises, the organism seeks food.

There is fear, but there is no sustained awareness of an inevitable end.

Reality is immediate and actionable.

M.O.R.T. marks the moment when human cognition crossed a threshold.

Our ancestors became capable of understanding not just threats, but outcomes. Not just danger, but inevitability.

They could imagine the future, reflect on themselves, and recognize that no amount of intelligence, strength, or cooperation ultimately prevents death.

That level of awareness should have been catastrophic. A creature that fully understands its own unavoidable extinction should freeze, withdraw from risk, fail to reproduce, and disappear from the evolutionary record.

According to Varki and Brower, we didn’t disappear because something else evolved at the same time. The ability to let the mind partially override reality. To soften, distort, postpone, or symbolically reframe what is known: M.O.R.T.

M.O.R.T. is not about denying facts. It’s about regulating attention. It allows the mind to know something is true without holding it at full intensity. Mortality is understood, but kept in the background.

Present, but not paralyzing.

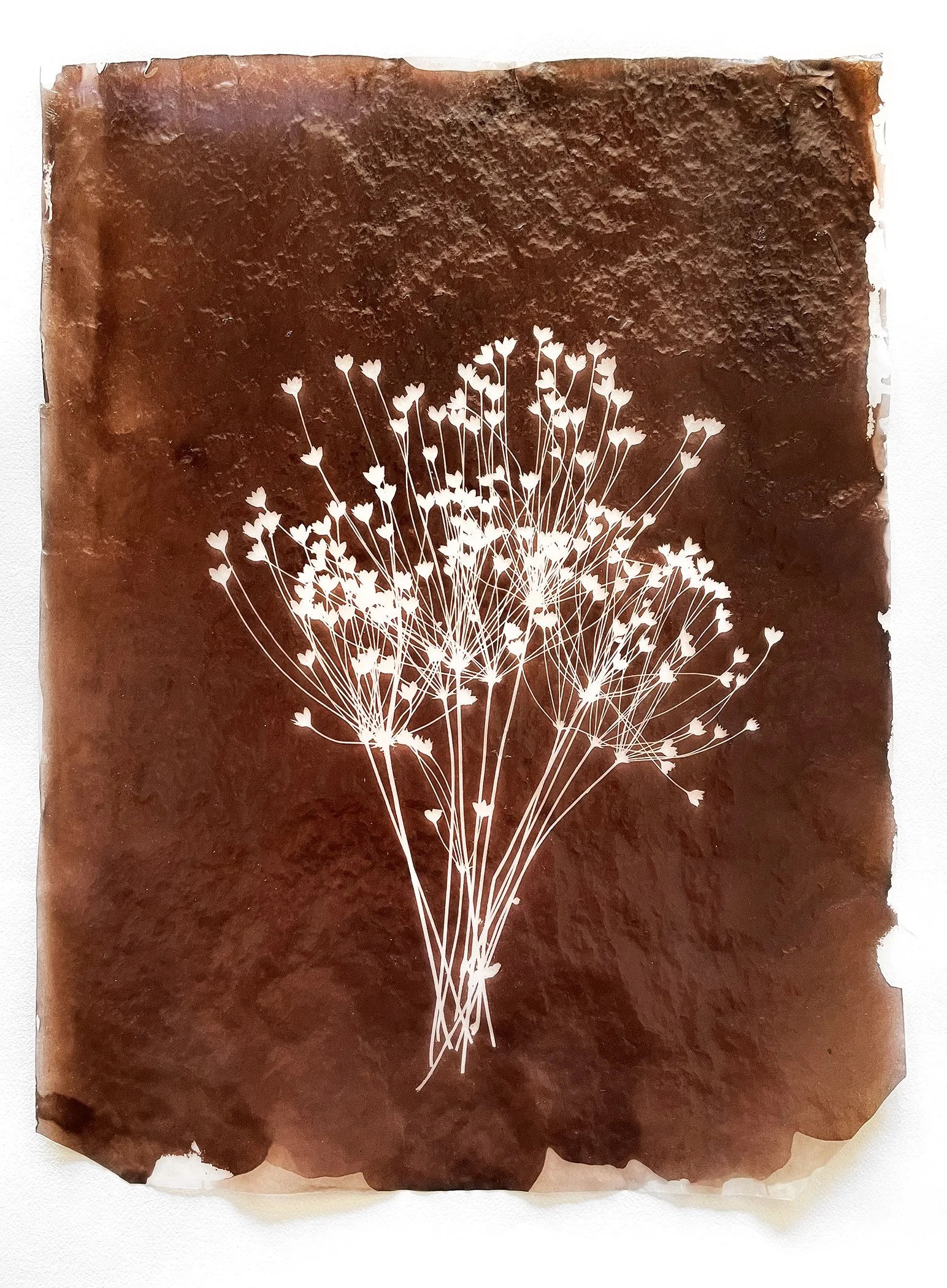

This is why humans can plan for the future, take risks, fall in love, make art, raise children, and build civilizations while fully aware that all of it ends. The mind learns to place symbolic meaning, narrative, and purpose between itself and raw reality.

In this sense, M.O.R.T. is not a flaw. It’s an adaptive solution. A psychological buffer that makes consciousness livable.

And once that buffer exists, everything we call culture becomes possible. These aren’t secondary inventions layered on top of survival. They are how survival continues in the presence of unbearable knowledge.

If the full weight of mortality stayed fully present all the time, the system would collapse. Panic. Paralysis. Withdrawal from risk. Failure to function.

That softening is everywhere once you know how to look for it. You can recognize it in yourself, too.

This is where Varki and Brower quietly meet Ernest Becker. Becker argued that culture is a defense against death.

Varki and Brower push the idea deeper. They suggest that the capacity for defense is built into the structure of consciousness itself. We don’t just learn denial through culture. We inherit the ability to manage reality through it.

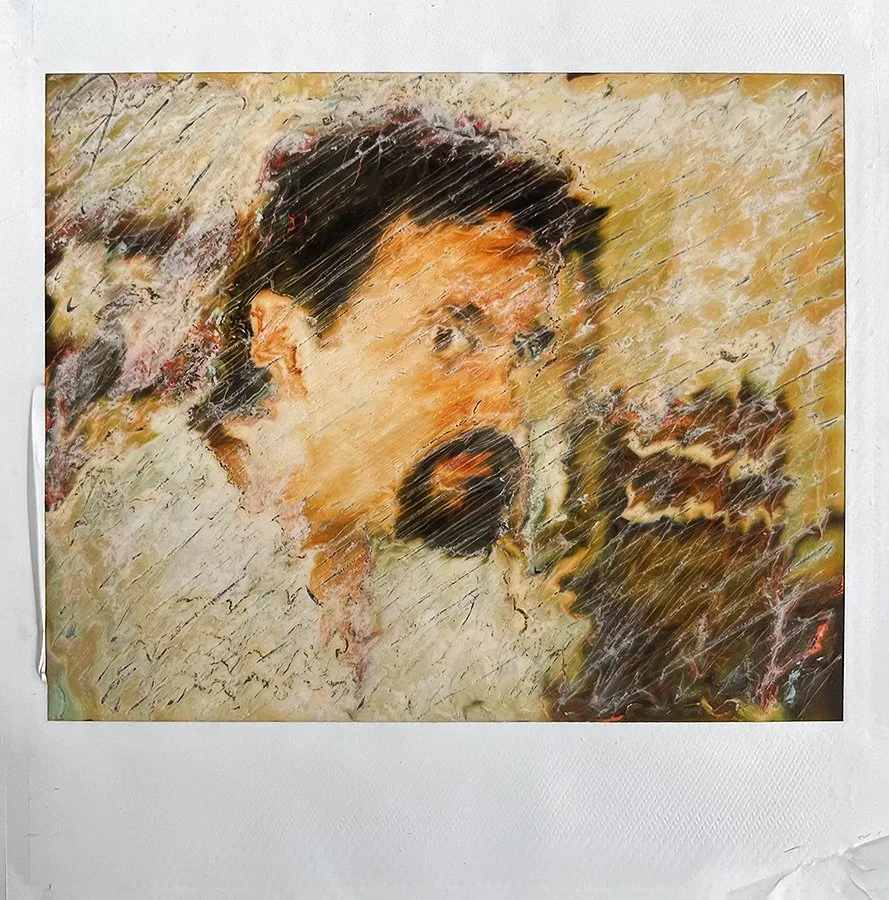

Once that sinks in, creativity stops looking like decoration.

It stops looking like leisure or self-expression.

It begins to look like a survival strategy.

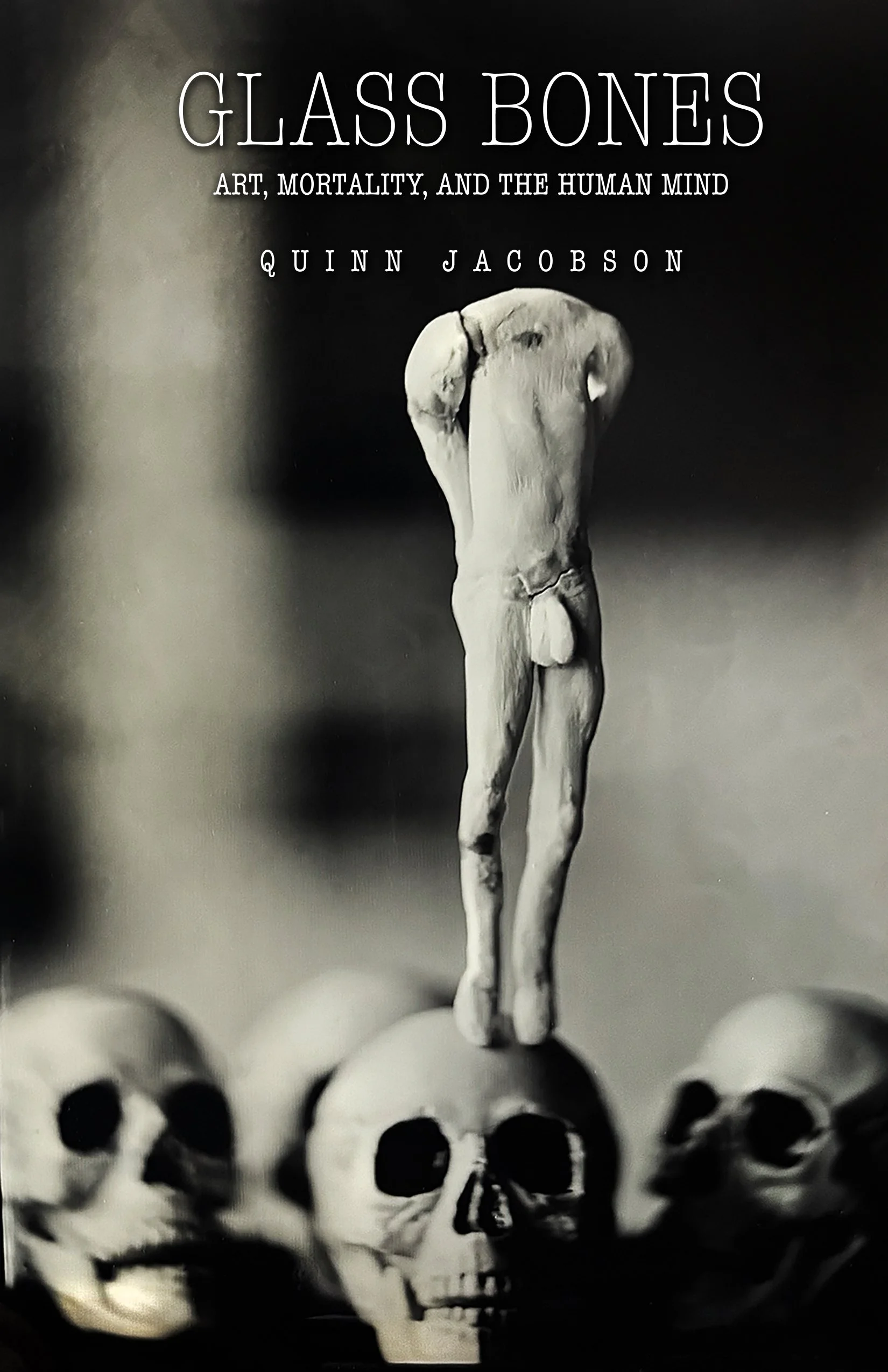

Making images.

Telling stories.

Leaving traces.

Building meaning systems.

These are not optional human add-ons. They are how a symbolic animal stays operational while knowing the end is coming.

This is where my own work keeps pressing.

Artists tend to stand close to that fault line.

We turn the dimmer switch up more often than most.

We look longer.

We tolerate more exposure.

Sometimes we manage to metabolize what we see into form.

And sometimes it nearly breaks us.

In plain terms, Varki and Brower are saying this: humans survived not because we learned the truth, but because we learned how to live near the truth without being destroyed by it.

That tension, between knowing and not knowing too much, is the thread I keep following. It’s where consciousness fractures, culture begins, and art becomes necessary.