In this conversation, I sit down with Dr. R. Michael Fisher for Careers of Folly and Wisdom (Episode 3) at the close of 2025, and we trace the strange overlap between two lives shaped by study, teaching, and the long arc of existential pressure. What begins as a simple introduction quickly becomes a deeper exchange about why some ideas take decades to name and why the hardest work is often learning how to speak those ideas in public without having them reduced to something smaller.

We talk about how we connected through Southwestern College’s Visionary Practice & Regenerative Leadership doctoral program and why I went searching for faculty whose work could actually hold what I’m building: an arts-based inquiry into creativity, mortality, and the psychological machinery of denial. I share my early “folly” at residency, where I became “the death guy” despite my real focus being the opposite: what happens inside the dash between birth and death, and how the knowledge of impermanence reshapes a human life. That misreading became a kind of field experiment in real time, revealing how quickly people reroute mortality talk into safer channels like grief, loss, or therapeutic language. It also forced me to sharpen my communication, not by diluting the thesis, but by learning how to meet the audience where the “dimmer switch” is already working.

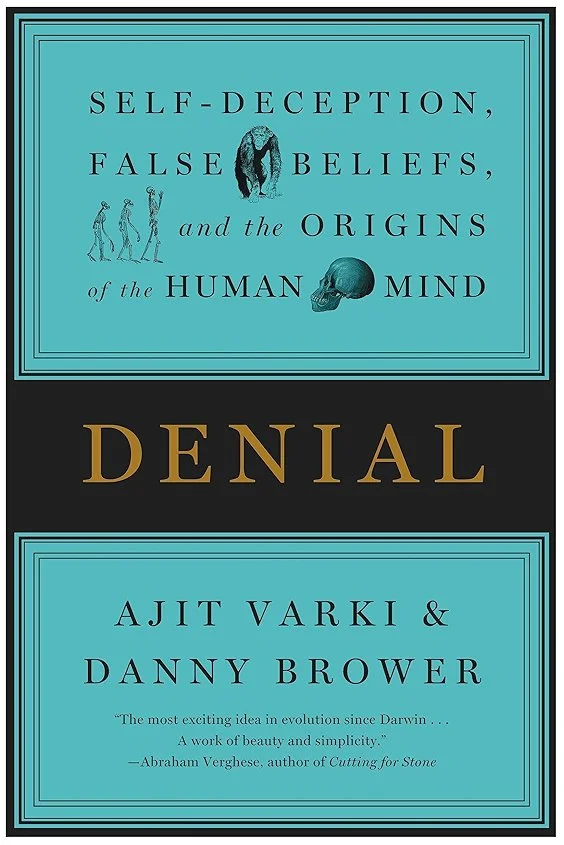

From there, the conversation widens. Dr. Fisher pushes on the themes of education, fallibility, and maturity: how a person with deep content and lived experience learns to teach without preaching, and how humility becomes an actual method. I bring in two foundational touchstones that anchor my work: Becker’s insistence that death terror is a mainspring of human activity and Rank’s claim (via Becker) that the artist takes in the world and reworks it rather than being crushed by it. That tension is the engine of my research question: if most of culture is organized to keep death out of view, what do artists do differently with that same pressure, consciously or unconsciously?

A major thread running through the interview is that denial is not just a personal quirk. It’s cultural, political, and historical. I talk about early experiences that formed my worldview, including family stories that complicate simple narratives of “normal” American life, and how those early exposures shaped my sensitivity to power, erasure, and the stories nations tell themselves. We also move into my military background, where I describe the kind of learning you don’t go looking for: the collision between youthful exceptionalism and the realities of violence, trauma, and institutional harm, including witnessing suicide deaths while working as a photographer. The folly, as I name it, is the arrogance of certainty; the wisdom is the painful clarity that comes after the myth breaks.

In the final stretch, we pivot to Dr. Fisher’s work in fearology and his reframing of Terror Management Theory as, in many ways, a kind of “fear management education.” That exchange matters because it shows the real stakes of language: fear, terror, anxiety, and denial. These aren’t interchangeable terms, and both of us have been forced to grapple with how quickly audiences collapse complex ideas into familiar clichés. We end with a concise statement of my own working thesis, offered almost like a poem: artists tend to give anxiety form rather than discharge it through denial; material practice slows experience enough for mortality to move into objects; rupture is where meaning fails, and art often happens there; the ethic is not to “fix” the break, but to stay present with it.

The conversation closes on an honest note about the cost of passion. We talk about parenting, devotion to work, and the ways even meaningful lives leave blind spots in their wake. If this episode has a through-line, it’s that wisdom is rarely clean. It comes out of misfires, misreadings, and the slow work of learning how to hold the real without turning it into a brand, a sermon, or a therapy session.

I really enjoyed the conversation, and I look forward to working with Dr. Fisher. Check out his YouTube channel and his other interviews and commentary.