I recently read Alan Blum’s article, Death, Happiness and the Meaning of Life: The View from Sociology (2014), and it hit close to home.

For all the talk we hear in sociology about class, structure, or behavior, mortality rarely gets its due. Blum makes the case that death is in fact a ghost that haunts the foundations of classical sociology—even if it rarely shows its face. Think Durkheim, Marx, Weber, and especially Simmel. The question of death isn’t absent—it’s just buried under the weight of categories, work ethics, and ideal types.

Blum argues that modern bourgeois life is built around avoiding death and ignoring the deeper questions of meaning. He calls it “practical thinking,” but what he’s really pointing to is a kind of cultural anesthesia. We’re trained to keep death at arm’s length—personally, socially, and even academically. Happiness becomes the pursuit, and death becomes the thing that threatens it.

That’s not new, of course. Ernest Becker said the same thing in The Denial of Death. Otto Rank said it decades earlier. But what Blum does is bring this denial right into the heart of sociological theory, and in doing so, he opens a door most people would rather leave shut.

The Artist’s Role at the Edge

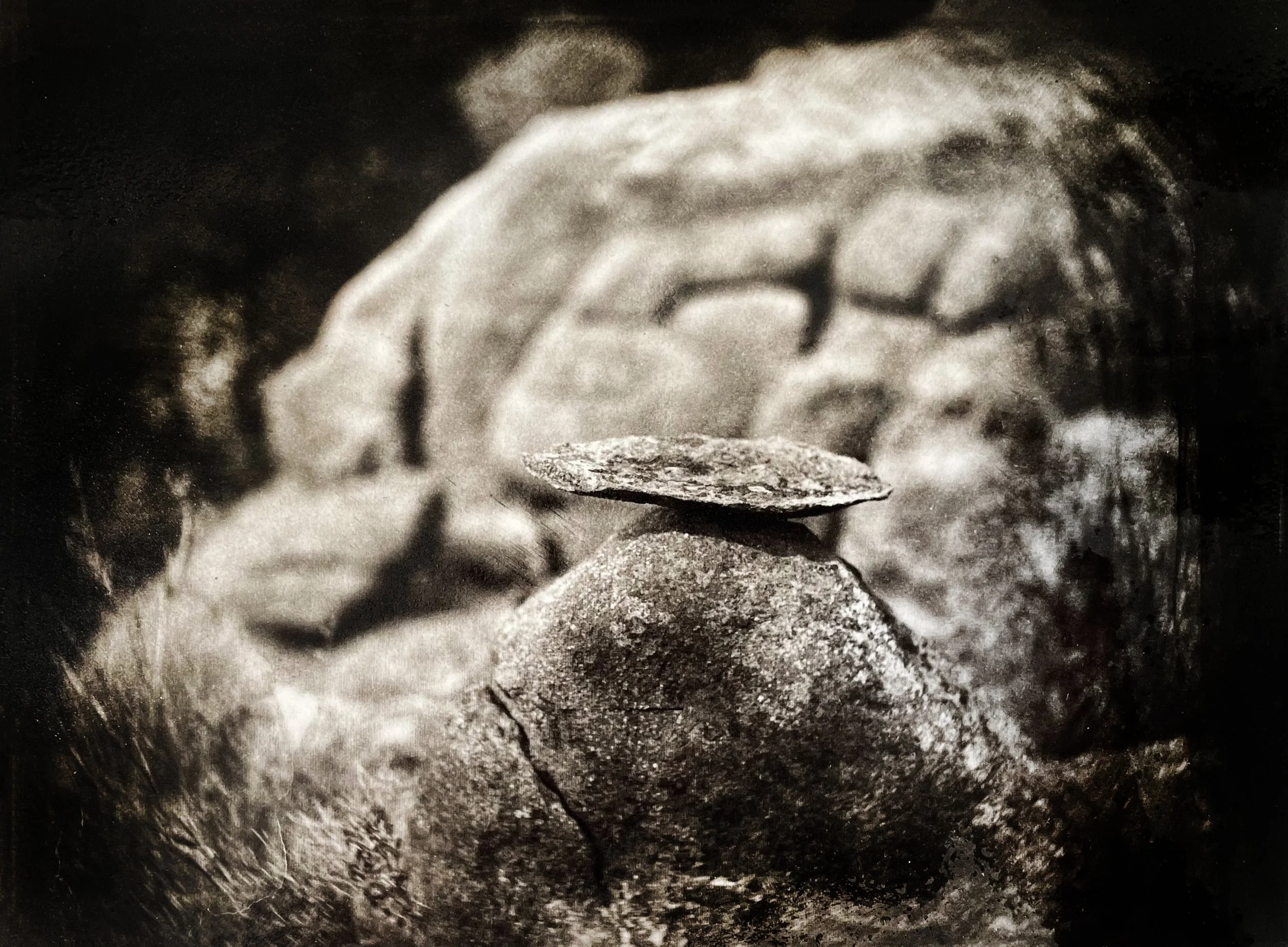

I connected with his treatment of Georg Simmel—the only classical theorist who didn’t shy away from death. Simmel saw death as form-giving. That phrase stopped me. Death gives shape to life. It makes us ask the questions that matter. It compels us to create, not just to produce. And it demands we live with a sense of form—of meaning, of purpose—not just survival.

Simmel writes, “In every single moment of life we are those who must die” (2007, p. 73). That awareness changes how we live—if we’re awake to it. Most aren’t. Most sleepwalk through life, as Heraclitus might say, distracted by the day-to-day. And that’s by design. Bourgeois culture has given us the tools to stay asleep: comfort, consumption, self-optimization. The pursuit of happiness has become a cultural sedative.

But artists don’t get to sleep. At least not the kind I’m interested in. We stand at the edge, facing death, and we make something out of it. It’s not a job—it’s a necessity.

Death as a Sociological Force

Blum reads Durkheim, Marx, and Weber through this lens too. Durkheim didn’t ignore death; he just buried it in statistics. In Suicide (1951), he shows how social categories—gender, class, religion—impact life and death. But those categories are dead until they’re animated by lived experience. Until they speak.

Weber saw death anxiety expressed through the Protestant work ethic—a compulsive need to prove one’s worth in the absence of salvation. And Marx saw the whole capitalist machine as a distraction from the futility of existence. The bourgeoisie keep moving, keep acquiring, keep revising their résumés because they can’t bear to stop and ask what any of it means.

Sound familiar?

It should. It’s the same story Becker told, just told in different language. And it’s the story many artists live—especially those of us working at the edge of history, memory, and mortality.

Against the City, Toward the Limit

Blum uses “the city” as a metaphor for this cultural deadening. The city is where goods circulate, people chase happiness, and no one wants to talk about death. In Lacan’s terms, the city is the site of desire detached from meaning. It's where the bourgeois dream is kept alive—not by truth, but by repetition.

But death always slips through the cracks.

It shows up in our dreams, our breakdowns, our art. And when it does, it brings everything into question. That’s what Blum calls “thinking at the limit.” It’s what I think of as the necessary work of the artist. Not to romanticize death, but to sit with it. To refuse the lie that happiness is the point of life. To tell the truth, even when that truth is uncomfortable.

Final Thoughts

This article reminded me why I make the work I make. Why I write the way I write. Why I teach what I teach. It’s not about mastering death. It’s about refusing to forget it. Because when we forget death, we lose the thread. We start making things that don’t matter. We trade meaning for comfort. We become the living dead.

Simmel refused that trade. So did Becker. So do the artists I admire most.

Facing death isn’t about morbidity—it’s about vitality. It’s about making something honest in a world that keeps asking us to look away. That’s the work.

That’s the only work.