We don’t really talk about death anymore—not in any meaningful way. We dress it up in ritual, drown it out with noise, and spin it into spectacle. Somewhere along the way, we stopped treating death as a mirror and started treating it like a mess to be cleaned up. But as Martin Heidegger once argued, our relationship to death isn’t just a philosophical curiosity—it’s the foundation of an authentic life.

In Being and Time, Heidegger introduced a concept that should hit all of us squarely in the gut: Being-towards-death. Unlike animals, humans are aware of their own mortality. We don’t just die—we know we’re going to die. And that knowledge, if we let it in, can radically change the way we live.

But we rarely do. Most of us live in what Heidegger calls “everydayness,” where death is something that happens to other people. We skim the obituary page. We attend the funeral. But we never fully absorb the fact that we’re next. Instead, we flee into distraction, comfort, and consumption.

This is what the author of a recent paper called the “loss of death-to-life reference.” In simpler terms: we’ve lost the thread. Death used to point us back to life, to meaning, to what matters. Now, it’s buried under carnival tents and beer stands at modern funerals, turned into an opportunity to sell trinkets, drown pain, and avoid reflection.

Heidegger believed that to live authentically, we must turn toward our own death—not in morbid fascination, but in honest acknowledgment. He said we should live with death as a “pure possibility,” always present but not yet actualized. It’s not about dwelling on death. It’s about letting it shape the urgency of our days.

And here’s the paradox: when we face death head-on, life sharpens. Viktor Frankl put it well—if we were immortal, nothing would matter. We could postpone everything forever. But because we’re finite, we’re called to act, to love, to create now.

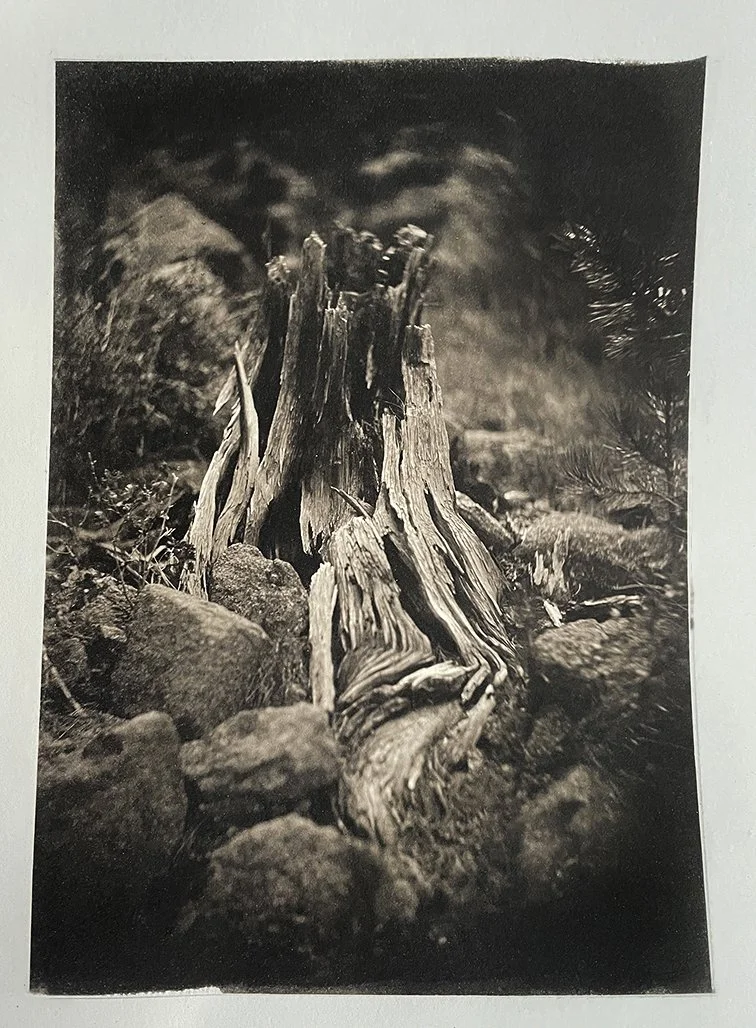

This isn’t a plea for some stoic resignation or heroic denial of grief. Death hurts. The loss of someone we love breaks us. But the pain of death can also become a kind of teacher. It reminds us that life is not just a timeline—it’s a trembling, temporary flame. And the way we treat that flame—our own and others’—reveals everything about who we are.

There’s nothing inherently meaningful about death. But the awareness of it? That’s different. Death awareness can crack open the shell of ego and force us to ask the questions we spend our lives trying to avoid. What matters? What lasts? What have I been avoiding because I thought I had time?

Modern culture isn’t designed to help us answer those questions. It’s designed to numb them. That’s why reclaiming the existential weight of death is not just personal—it’s cultural. It’s spiritual. It’s ethical.

So here’s the real question: What would your life look like if you lived it with the constant awareness that it’s going to end?

Not someday.

Not in theory.

But for real.

Sooner than you think.

That’s not meant to depress you. It’s meant to wake you up.