Coping Mechanisms

In "The Last Messiah," Zapffe postulates four main methods humans have used for limiting the contents of their consciousness, including:

Isolation, which involves “a fully arbitrary dismissal from consciousness of all disturbing and destructive thought and feeling,” It is an avoidance of thinking about the human condition and the terrible truths that Zapffe believes this entails. He also describes the technique of isolation by quoting a certain "Engstrom," whose identity remains uncertain: “One should not think, it is just confusing.”

Anchoring involves the “fixation of points within, or construction of walls around, the liquid fray of consciousness.” This requires that we consistently focus our attention on a value or ideal (the examples Zapffe gives include "God, the Church, the State, morality, fate, the laws of life, the people, and the future”).

Distraction, which is when “one limits attention to the critical bounds by constantly enthralling it with impressions," prevents the mind from examining itself and becoming aware of the tragedy of human existence. It is easy to think of how we, in modern times, incessantly distract ourselves with external stimulation; some examples Zapffe gives include entertainment, sport, and radio.

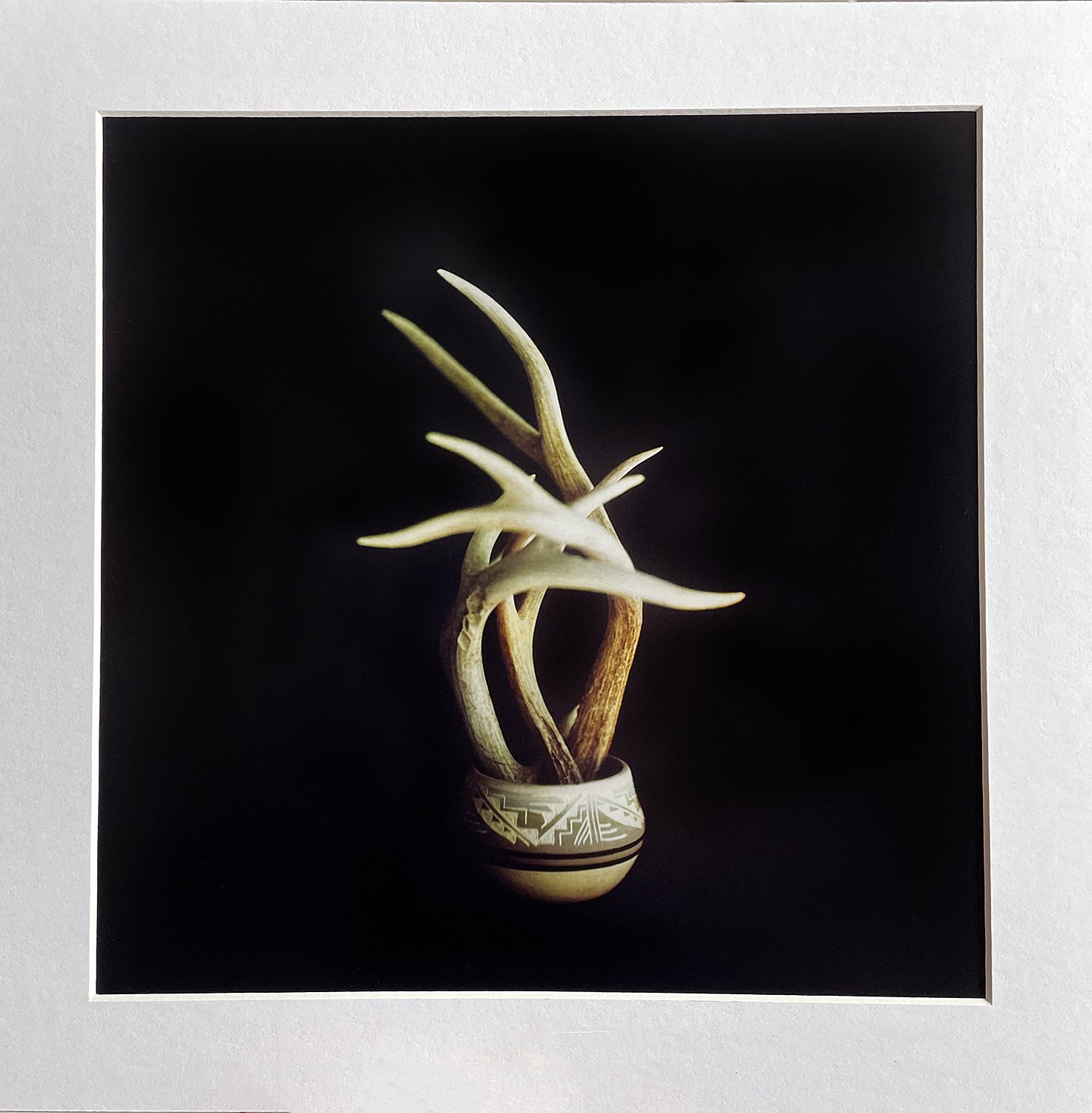

Sublimation, which Zapffe calls “a matter of transformation rather than repression,” It involves turning “the very pain of living” into “valuable experiences.” He continues: “Positive impulses engage the evil and put it to their own ends, fastening onto its pictorial, dramatic, heroic, lyric, or even comic aspects.” He also notes that the essay "The Last Messiah" itself is an attempt at such sublimation. For Zapffe, sublimation is “the rarest of protective mechanisms." Most people can limit the contents of their consciousness using the previous three mechanisms, staving off existential angst and world-weariness. But when these forms of repression fail and the tragic cannot be ignored, sublimation offers a remedy, a way of turning the unignorable “pain of living” into creative, positive, and aesthetically valuable works.

Is There No Room for Joy?

Comparisons have been made between Zapffe’s views on the human condition and sublimation to the thought of Friedrich Nietzsche. In The Gay Science (1882), Nietzsche writes: “Higher human beings distinguish themselves from the lower by seeing and hearing, and thoughtfully seeing and hearing, immeasurably more”. But this higher degree of sensitivity, of looking deeply into life, results in suffering. In The Birth of Tragedy (1872), Nietzsche, like Zapffe, defends the remedial effects of art: “The truly serious task of art…[is] to save the eye from gazing into the horrors of night and to deliver the subject by the healing balm of illusion from the spasms of the agitations of the will.”

When the first three repression techniques outline by Zapffe fail, which they do for a minority of people, then creative expression may be the only available means of coping with the “horrors of night," as Nietzsche put it. Arguably, the rarity of sublimation helps to explain why geniuses are also rare, as creative work is often the only saving grace for those people deeply attuned to the fullness of the human predicament. In the words of Aristotle: “No great genius has ever existed without a touch of madness.” Elsewhere Aristotle stated: “Those who have become eminent in philosophy, politics, poetry, and the arts have all had tendencies toward melancholia.” Many studies have indeed found links between psychopathology and creativity, with many such studies discussed in Dean Keith Simonton’s book Origins of Genius (1999).

To save oneself from becoming overwhelmed, panicked, and despondent, creative work acts as a protective mechanism, as Zapffe argues, although such creative expression may be regarded as more valuable than simply protection against consciousness; it can be thought of as providing the very meaning that people yearn for, which Zapffe believes is unobtainable. Nietzsche, for instance, maintained that “To live is to suffer, to survive is to find some meaning in the suffering.” The psychiatrist Viktor Frankl also echoed the view that meaning can be found in our relationship to suffering. It is possible to transcend the sense of meaningless and hopelessness we have by creating something genuinely valuable and meaningful.

Here we can make a distinction between cosmic nihilism, which paints the universe as inherently meaningless and terrestrial nihilism, which treats all of human life and activity as meaningless. Even pessimistic philosophers such as David Benatar concede that human life can be meaningful. We don’t have to fall into terrestrial nihilism, as well as cosmic nihilism. By advancing meaning in terrestrial, human affairs, the panic that Zapffe alludes to may only hold true when we take the cosmic perspective. Furthermore, if meaning can be found in transforming one’s own suffering or that of others, then this could entail actions that go beyond sublimation. There seems to be discoverable meaning for people — such as being of service to others or serving something bigger than oneself — that could be defined as an intrinsic part of the human condition, rather than a way of escaping the human condition.

On Zapffe’s point that our surplus of consciousness is to blame for the unique experience of existential angst and depression, I think it could be equally claimed that this surplus also enables converse feelings of existential joy. Of course, it can be disputed as to whether the existential angst is what comes more easily, but at least in cases of rarefied genius, so those people who cannot repress consciousness like the majority do, there is often a great capacity for joy, as well as sorrow. This seems to hinge on these people’s sensitivity to the totality of one’s individual consciousness, the human condition in general, and the world at large. Thus, just as despair can accompany any ordinary day, in solitude with one’s mind, so can ecstasy. One becomes open to the wide range of human experience and emotion, and privy to its depths and intensities.

As a case in point, Nietzsche experienced extreme states of suffering, both physical and psychological in nature, and focused much of his work on the problem of human suffering; but Nietzsche nonetheless seemed open to intense joys as well. He writes:

The intensities of my feeling make me shudder and laugh; several times I could not leave the room for the ridiculous reason that my eyes were inflamed — from what? Each time, I had wept too much on my previous day’s walk, not sentimental tears but tears of joy; I sang and talked nonsense, filled with a glimpse of things which put me in advance of all other men.

In the preface to The Gay Science, he also spoke of the elation and hopefulness that can follow a confrontation with suffering:

This book might need more than one preface; and in the end there would still be room for doubting whether someone who has not experienced something similar could, by means of prefaces, be brought closer to the experience of this book. It seems to be written in the language of the wind that brings a thaw: it contains high spirits, unrest, contradiction, and April weather, so that one is constantly reminded of winter’s nearness as well as of the triumph over winter that is coming, must come, perhaps has already come. . . Gratitude flows forth incessantly, as if that which was most unexpected had just happened — the gratitude of a convalescent — for recovery was what was most unexpected. "Gay Science": this signifies saturnalia of a mind that has patiently resisted a terrible, long pressure — patiently, severely, coldly, without yielding, but also without hope — and is now all of a sudden attacked by hope, by hope for health, by the intoxication of recovery. Is it any wonder that in the process much that is unreasonable and foolish comes to light, much wanton tenderness, lavished even on problems that have a prickly hide, not made to be fondled and lured? This entire book is really nothing but an amusement after long privation and powerlessness, the jubilation of returning strength, of a reawakened faith in a tomorrow and a day after tomorrow, of a sudden sense and anticipation of a future, of impending adventures, of reopened seas, of goals that are permitted and believed in again.