This is a reading of the book, "The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life" by Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg, and Tom Pyszczynski. Quinn will read a chapter every week and then have a discussion about it. This book, along with "The Denial of Death" by Ernest Becker is the basis for Quinn's (photographic) book, "In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of Othering and the Genesis of Evil."

The Worm at the Core: Chapter 2: The Scheme of Things

Join me on Saturday, March 25, 2023, at 1000 MST for the second chapter of “The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life.” (Solomon et al.)

This chapter is called “The Scheme of Things.” We’ll get into some of the behaviors that death anxiety drives, and they will surprise you.

The "scheme of things" means what?

What is psychological security, and why is it so important?

When do we start concerning ourselves with the knowledge of our impending death?

How do we form our cultural worldview?

Why are symbols so important to us?

What is a “cultural construct,” and why are my beliefs so fragile?

Why do I defend my beliefs so fiercely?

I hope you can join me!

These readings are in service of my new book, “In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of Othering and the Origins of Evil.” I hope to publish this work in 2024. The four books that this work is based on are The Denial of Death (E. Becker), The Birth and Death of Meaning (E. Becker), Escape from Evil (E. Becker), and The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life (Solomon et al).

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/live/90RRiitymwY?feature=share

Stream Yard: https://streamyard.com/wkfm2x3jg4

You can download the PDF of the book here.

“Deer Antlers & Wooden Buffalo Head,” whole-plate toned cyanotype from a wet collodion negative. From the project, :”In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of Othering”

Our Struggle To Be Unique

Ernest Becker said, when talking about being unique, “it expresses the heart of the creature: the desire to stand out, to be the one in creation. When you combine natural narcissism with the basic need for self-esteem, you create a creature who has to feel himself an object of primary value: first in the universe, representing in himself all of life.” Simply put, we want attention and adoration. We will go to great lengths to get it, and sometimes it manifests as narcissism. It's everywhere in society, especially with social media. It’s given us a clear example of this behavior (and need). Posting an endless stream of "selfies" and showing the "ideal lifestyle"—travel, wealth, high-end material goods, famous friends, popularity, etc.

I know that most people never think about their struggle for self-esteem (to find meaning and significance); not consciously anyway. It’s a daily battle for most human beings. This drives most human behavior after the basic needs are met, and most people don’t even know it.

If you look at Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, you’ll find what human beings spend their time doing every day. The basic requirements include physiological and safety needs. We need to breathe, eat, sleep, have shelter, safety, etc. These show the first survival drives, which include reproduction. Becker would call these "animal needs." Like all other animals, we are not exempt when it comes to the basic survival and reproduction drives. This is, in fact, what collides with our knowledge of death and creates the anxiety that we repress through self-esteem and culture.

“It is quite true that man lives by bread alone — when there is no bread. But what happens to man’s desires when there is plenty of bread and when his belly is chronically filled? At once other (and “higher”) needs emerge and these, rather than physiological hungers, dominate the organism. And when these in turn are satisfied, again new (and still “higher”) needs emerge and so on. This is what we mean by saying that the basic human needs are organized into a hierarchy of relative prepotency.”

As you climb up the Maslow ladder, you see where this changes. I like Maslow’s theory. And for the most part, I agree with it. Where I would differ is how these are separated. Love and belonging, self-esteem, and self-actualization can all be put into one category: self-esteem. We can never really attain self-actualization. This is a goal set in this theory to strive toward (the carrot on the stick). Self-actualization gives you a way to look for and get a steady supply of self-esteem. Becker calls this "culture" or "cultural worldview."

Culture provides a way we can bolster and maintain our self-esteem, and self-esteem keeps our existential terror (death anxiety) at bay. Self-esteem buffers anxiety. “Psychological equanimity also requires that individuals perceive themselves as persons of value in a world of meaning. This is accomplished through social roles with associated standards. Self-esteem is the sense of personal significance that results from meeting or exceeding such standards.” (The Ernest Becker Foundation)

“I was no longer needing to be special, because I was no longer so caught in my puny separateness that had to keep proving I was something. I was part of the universe, like a tree is, or like grass is, or like water is. Like storms, like roses. I was just part of it all.”

From here, we can understand the need for self-esteem. We have to have it; if we don’t, psychological pathologies, namely depression, will emerge. The question becomes one of balance. How do we balance our need for self-esteem and yet keep narcissism at bay? Bolstering self-esteem and narcissism are sometimes very difficult to tell apart.

Once we have self-esteem (meaning and significance), we can operate day-to-day with what most would call "normalcy." Our self-esteem comes from our culture, which is a shared reality that tells us what to believe and how to act to boost our self-esteem. When this cultural worldview is threatened or questioned, we get angry and go to great lengths to defend it. And the deeper we believe or cling to our worldview, the more extreme our response to a threat will be. Herein lies the problem. This is the crux of my project.

“Half of the harm that is done in this world is due to people who want to feel important...they do not mean to do harm...they are absorbed in their endless struggle to think well of themselves.”

"Paradise Cove, Colorado": whole-plate palladiotype print on Revere Platinum paper from a dry collodion negative. The negative was exposed for 4 minutes at f/5.6. This scene is 9,000 feet above sea level in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, May 2022, for my book "In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of "Othering."

The first word that comes to mind when I look at this print is "alien." The dictionary definition is: "a foreigner, especially one who is not a naturalized citizen of the country where they are living." I think about this a lot. I ponder how people end up living in a place that was stolen from the original people of the land. I think I know how it happens, and moreover, why!

The small Ponderosa Pine tree growing out of the granite—granite formed by ancient volcanoes in the area—stands out to me as well. Again, it makes me think about the people who lived here before the colonizers arrived. And I can feel the passing of time in this photograph. It feels old. In fact, it feels ancient and mysterious to me—a place that’s seen so much happen over time. It puts my finitude and smallness in perspective.

My Plans: Spring, Summer & Autumn 2023

“The bitter medicine he prescribes — contemplation of the horror of our inevitable death — is , paradoxically , the tincture that adds sweetness to mortality .”

Winter in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado is not over yet, but my mind is already thinking ahead to spring, summer, and autumn. I’m starting to make plans to work on my project again. It’s not too far off, and I’m excited to start making photographs again.

In the winter, I go into "photographic hibernation." I shut down the studio and darkroom, and I only go into the building (maybe) once a month to check on things. I thought it would drive me insane not to be able to create images all winter. I’ve found quite the opposite. In fact, I would recommend taking a break from the craft and working on the concept with no distractions—it’s been a great way for me to see, with more clarity and purpose, what I’m trying to do. I think I’m making my best work by writing for a few months and making images for a few months. I've found that time is the greatest asset when creating work like this. I've never had such distraction-free time before, and I'm beyond grateful for it. Rollo May said, “Absorption, being caught up in, wholly involved, and so on, are used commonly to describe the state of the artist or scientist when creating or even a child at play. By whatever name one calls it, genuine creativity is characterized by and intensity of awareness, a heightened consciousness.“

In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of “Othering” (example book cover)

My book, In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of “Othering”, is going to be my "magnum opus." I’m not saying that it will be my final body of work, but it will completely close this chapter of inquiry for me. It’s literally a body of work, both written and photographed, that examines questions that I’ve wrestled with for over 30 years of my life. It’s a big deal to me, and I hope it resonates with a few other people. I know it’s a difficult topic to get people interested in; it’s not something that’s addressed much, but it should be. That’s the very point of this work. Through the historical events of the 19th century, I’m telling the story of “othering” (xenophobia) and what happened to the Tabeguache Utes that lived on the land where I now live.

This is not a body of work that documents the Tabeguache Utes, but explores the land, plants, objects, and symbols they used here. My objective is to explore the denial of death and the negative consequences it bears when it’s not directed in a positive, non-destructive way. This book will address why things like this happen and will continue to happen. I feel like it’s a unique blend of art, history, and psychology that applies to every human being and all human behavior.

Making art, especially a large body of work on a specific topic, is an interesting process to go through. I’ve done it several times in my life, but this is different. As I just mentioned, this is the culmination of all of my previous work. It reveals answers to the questions I’ve been asking for so long. It feels like I’ve worked on smaller projects to warm up for this. I’m beyond excited about all of it.

I'm not sure what the next chapter of my life will bring. I’m not even sure it will be photography. I find my interest in traditional photography waning. Don’t misunderstand me; I love photography, but my interest is waning in how it’s being used today and how it’s changed over the years. Even the purpose of working with historic processes (something that should be very special) has turned into something that I don’t recognize and have no interest in. Everything feels exploited and commodified to me.

“Absorption, being caught up in, wholly involved, and so on, are used commonly to describe the state of the artist or scientist when creating or even a child at play. By whatever name one calls it, genuine creativity is characterized by and intensity of awareness, a heightened consciousness.”

It seems that most people working in these processes are firmly rooted in commercial work or are immersed in constant technical talk about processes and equipment (I’ve written several essays on this topic). There seems to be so little real output of expression or ideas using these processes. To be honest, it bores me to death; I have nothing left to say about it. So whatever I do next, I'll be prepared for it. If it involves photography, it won’t be commercially based or solely technical—it will be personal and expressive. It'll come to me naturally and organically, just like this work and my previous work have.

PLANS FOR THIS YEAR

For 2023, I’m going to continue to work on the “flora” portion of my project. I have several more plants I want to photograph as well as try some new approaches to making these images. There are quite a few landscape images I’m after, and I'll attempt some “fauna” work as well. I’ll continue to work it out and discover new ways to communicate these ideas semiotically.

I’m still very much in "creation mode" for the project—work, work, work—meaning that I’ll spend a few months editing a lot of photographs (about 200 images) and deciding what best represents my ideas for the concepts. I’m sitting on about 130 negatives from the work I did last year (2022). These are wet and dry collodion negatives, as well as paper negatives (calotypes). I have about 30 to 40 photogenic drawing prints and cyanotypes, too. I’ll have several print-out-processes to select from as well. Different negatives print differently in various P.O.P. processes. Even the paper selection can make a big difference. It's a lot of work, but it's also a lot of fun.

This year, I plan to do another 100–125 negatives plus several photogenic drawings and cyanotypes. I want a large variety to work with. The book will have between 75 and 100 images. To get that, I’ll need about 200 images to edit from. They will vary in process, too. There will be palladiotypes, kallitypes, salt prints, gelatin and collodion aristotypes, cyanotypes, Rawlins oil prints, and photogenic drawing prints. The substrate and execution will vary too. I’m going to try to make some very interesting images involving both content and process. They will be unique and, hopefully, engaging and interesting. That’s the goal. I want the visuals to connect with and represent the writing (concept) of the work more than anything else.

I’m thinking that this year’s work won’t be shared online. As much as I like sharing the work, I think I may keep this second year to myself. When I publish the book, I want most of the images to be "new" to the viewers. I think that seeing the photographs in the book with all of the text available adds more power to the concept. I hope those interested will stay tuned for the book. It will be worth the wait, I promise.

MY THOUGHTS ON SHARING, & SOCIAL MEDIA

I enjoy sharing work with people online. Most of the time, it’s a very positive experience. It builds community and is generally a positive thing. I try to stay away from the contentious stuff and just share with those that are interested. That will change somewhat over the coming year and the rest of this work. I’ll explain why.

I’ll continue to publish essays here (on my blog) over the coming year. This is like a public journal for me. I “exercise” stuff from my mind here; it’s cathartic for me. Sometimes, I’ll even come back to it to find something I’ve written about or a reference. It’s a good thing for me. And to those that read it, thank you, and thanks for the positive and kind words about it. So what about social media?

Social media has a tight grip on all of us—too much control over our personal, artistic, and creative lives. Too much influence is placed on what people will "like" or not, and the number of “likes.” Why do we put so much weight on social media? We want those dopamine hits! I get it.

Beyond that, there's surveillance capitalism and the data these large corporations are gathering on us via these platforms—it's intrusive and scary! We give it to them freely and ignorantly. Every Facebag survey you take on "What Kind of Potato Are You?" (or some other ridiculous thing) is simply getting more information about you to sell you stuff that you don’t need. These platforms are constantly encouraging people to compare themselves to each other (especially dangerous for young people). And the algorithms determine what will keep you scrolling for hours on end—so-called doom scrolling—and then feed it to you on an endless loop.

There’s so much negativity on these platforms. That alone should keep us away, but it doesn’t. The arguing and fighting over who is the best and smartest, as well as the "experts" shouting down, belittling, and degrading others, and the cultural and political squabbles, are heartbreaking. It's exactly what I read about and write about every day—existential uncertainty—and this is how people deal with the anxiety.

I see a lot of (malignant) narcissism on these platforms as well: “filtered selfies” and great lifestyles that are all fake. I get that people use it to bolster their self-esteem—life is difficult and frightening, and the knowledge of our impending death (death anxiety) drives us to deny it and act out this way—and social media assists in doing exactly that. In his book The Denial of Death, Ernest Becker said, "But it is too all-absorbing and relentless to be an aberration; it expresses the heart of the creature: the desire to stand out, to be the one in creation. When you combine natural narcissism with the basic need for self-esteem, you create a creature who has to feel himself an object of primary value: first in the universe, representing in himself all of life."

Every day, people post something that says, in essence, "Please like me and validate my existence; I seek meaning and significance." This is what Becker talks about constantly in his books. I wish there was a viable alternative. When I first started the Collodion Forum Board in 2003, there was a great community there. It lasted for a few years. People were courteous, kind, and generous with their knowledge and information. It didn’t have all of the negative aspects that we see on social media today (photo groups and egos). A lot of people working in wet collodion today got their start there - in fact most of them. Times change, and we move on. I wax nostalgic.

I think I can convince people that there are better and healthier ways to bolster their self-esteem. My book has nothing to do with "self-help,” but it will talk about ways to deal with death anxiety without being so self-centered and destructive.

There are some positive things about social media (very few things), but as a whole, the liabilities outweigh any of the good or positive things. I want to break the rules and try something different, like not sharing everything I make. How novel is that?

MOUNTAIN LIVING & SOLITUDE

I’ve had a few months of writing and time to lay out the book for its first iteration. So far, I feel great about what I’ve written. The writing has really allowed me to think about the photographs I want to make. This time has been priceless in that way. I write every day, seven days a week, some days more than others, but I still write. And I read every day, too. I’m always looking for books, films, music, and art in general that may have some connection to these ideas. I take in a wide variety of information; it seems to help me make the connections I need to write about these theories. I’ve written a lot about being fully aware of how I’m using art and creativity to buffer my own anxiety. I would go even farther and say that I’m not only buffering the anxiety, I’m feeding off of it. In other words, I’m using existential terror creatively in my favor. I feel like I'm getting one over on my own death awareness.

“I am losing precious days. I am degenerating into a machine for making money. I am learning nothing in this trivial world of men. I must break away and get out into the mountains to learn the news. ”

This June (2023), we will begin our third year of living on the mountain. Living up here has definitely changed me. Maybe it’s the mountain air, the isolation, the peace and quiet, being close to nature and the wildlife, or a combination of all of it. Whatever it is, it’s had a big impact on how I view the world. It’s allowed me to see what’s important and what’s not. What I actually need and don't need, as well as the ability to say "no," sounds trite and cliche to say, but it’s true.

Time away from a toxic culture that influences your life without your knowledge resets your mind; it changes you. Living in cities and suburbs directs your life to the point where you become something you don't want to be: a conspicuous consumer—not just a consumer, but someone who is always looking for the next thing to buy, have, or be, endlessly seeking satisfaction but never receiving it. The big ontological question is: If we have everything, why aren’t we happy?

My changes are positive, fulfilling, and meaningful to me. I'm forever grateful to be here; we love this mountain. And I’m filled with gratitude to spend my days thinking about the human (paradoxical) condition, art, photography, and how to live each day of my life in the best way possible.

BY THE END OF 2023…

My hope is that by the end of this year, I’ll be going through prints and making selections for the book. I feel like I can have the writing mostly completed by the spring. There will be refinement and editing, but the bulk of it will be completed by June. I’ll work on it periodically throughout the year and have a final edit done by an outside resource.

Included in the book is an extensive autobiography. In fact, the second chapter, The Introduction, is where I write extensively about how my life (artistic and creative) unfolded and put me where I am now. It was an “eye-opener” to me. I think any artist or photographer will appreciate reading about my journey.

I’ve incorporated art, psychology, history, anthropology, theology, philosophy, sociology, and other disciplines to accomplish what I’ve set out to do with this book. I've had to combine all of the disciplines and theories in order to explain them so that people like me, a layperson, can understand them. I wanted the writing to be simple and understandable, not academic. It’s been a big chore, but it’s working.

The interdisciplinary approach to this work is critical. It truly supports the ideas in ways that one or two areas couldn’t. My goal is to make the art and my expression of these ideas the central theme. I want the photographs to act as a catalyst for understanding the psychology of "othering."

I feel like we don’t acknowledge the psychological underpinnings of photography enough. It’s easy to get academic about it, and again, I don’t want that. I want an authentic connection between the images and the psychology that they represent. So far, I feel very good about what I’ve accomplished. Let’s see what this year brings.

“We are all in search of a feeling more connected to reality... We indulge in drugs and alcohol, or engage in dangerous sports or risky behavior, just to wake ourselves up from the sleep of our daily existence and feel a heightened sense of connection to reality. In the end, the most satisfying and powerful way to feel this connection is through creativity. Engaged in the creative process we feel more alive than ever, because we are making something and not merely consuming, Masters of the small reality we create.”

“Antlers & Buffalo Head” Whole-plate (bleached and toned) cyanotype from a wet collodion negative.

Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In)

Do you remember this song? It's a psychedelic rock song written by Mickey Newbury and best known from a version by The First Edition (Kenny Rogers). It was used in the movie “The Big Lebowski.” He’s tripping in the bowling alley to the song. It was recorded in 1967 and released in 1968. I was four years old then. This song and "Quinn the Eskimo" (The Mighty Quinn), performed by Manfred Mann and written by Bob Dylan (The Basement Tapes), were very popular. Everyone started calling me "Quinn the Eskimo." I have vague memories of that time—good memories.

Both of these songs are about drug use (or so some think): LSD and quaaludes. It was the time of hippies and "awakening” and the sexual revolution. The war in Vietnam was raging, and the youth were rethinking capitalism, war, love, and the meaning of life—a significant shift in values from the parents of that generation. Ernest Becker said, “One of the reasons that youth and their elders don’t understand one another is that they live in “ different worlds”: the youth are striving to deal with one another in terms of their insides, the elders have long since lost the magic of the chumship. Especially today, the exterior or public aspect of the adult world, its jobs and rewards, no longer seem meaningful or vital to the college youth; the youth try to prolong the adolescent art of communicating on the basis of internal feelings; they may even try to break through the carapace of their own parents, try to get the insides to come out.” Ernest Becker (The Birth and Death of Meaning: An Interdisciplinary Perspective on the Problem of Man)

Ernest Becker was teaching his theories about death anxiety during this period. He had a difficult time staying employed. The universities saw him as a threat and a radical. He ended up in Canada (Vancouver, B.C.) and taught at Simon Fraser University until his death in 1974. Students loved Becker. He was a performer. They connected with his theories, too. I feel the same way. If you have an interest in the human condition, who we are, and why we are the way we are, as you should, these theories will be an awakening for you. They were for me.

I’ve been doing research and "deep diving" into Becker’s theories for a few years. There was a part of me that knew his ideas had answers for me. I've spent a lot of my life looking for answers to big questions, one of which is why we treat people who are different from us so poorly. There are so many examples of this throughout human history. Why haven’t we evolved past the point of committing genocide and subjugating other human beings as commodities and objects? We can put a man on the moon, but we can’t treat our brothers and sisters with basic respect? This is absurd to me! And this was a question that Becker had some preoccupation with as well. “In this view, man is an energy-converting organism who must exert his manipulative powers, who must damage his world in some ways, who must make it uncomfortable for others, etc., by his own nature as an active being. He seeks self-expansion from a very uncertain power base. Even if man hurts others, it is because he is weak and afraid, not because he is confident and cruel. Rousseau summed up this point of view with the idea that only the strong person can be ethical, not the weak one.” Ernest Becker (Escape from Evil)

My project, "In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of Othering," reflects my questions and answers a lot of them; questions that I’ve wrestled with for over thirty years. The strongest and most direct link I've made is between Becker's ideas about genocide, xenophobia, and the subjugation of other people and the events that have happened here (where I live)—the genocide of Native Americans by the colonizers and U.S. military.

Have I answered all of the questions surrounding these events? No. They’re far too complex for one body of work or a handful of theories to fully address. However, I feel like what I’m doing will create a catalyst to explore these events in ways very few have. The art (photographs) connects to the theories, and the theories connect to human behavior. I’ve drawn a straight line between all of them. It makes so much sense to me and satisfies me in ways that nothing else has over all of these years.

I know I’m swimming against the tide with this work. So few people will "get it," and even fewer will take the time to learn about it (people are simply not interested). I suppose that’s why we—humanity—keep doing the things we do (hate, genocide, racism, xenophobia, etc.). The terror of death is so profound that the need to repress it takes precedence over everything else, including learning about it. That’s "the condition our condition is in," and I don’t see it changing anytime soon. As Becker says, I’m not cynical, but I remain skeptical.

"Pigweed,” a photogenic drawing (Henry Fox Talbot, 1830s). This is an explosion of pigweed seeds. It’s how the plant reproduces. It’s a wild edible. Native Americans made tea from the leaves (used as an astringent). It’s also used in the treatment of profuse menstruation, intestinal bleeding, diarrhea, etc. An infusion has been used to treat hoarseness (voice) as well.

We're Animals, With One Caveat

I’ve never considered or really pondered the fact that I’m an animal. You’re an animal, too. What does this mean, or why does it matter?

It plays a significant role in the theory that I’ve been working on and studying for this project. It demonstrates the need for humans to isolate themselves (psychologically) from other animals. It’s a critical part of believing in our illusions—illusions to alleviate our death anxiety.

It doesn’t surprise me, though. As I peel this onion of human behavior, each layer reveals something new. I see where all of this fits and why it is the way it is—we need it this way to get out of bed in the morning,

These are cultural constructs to convince ourselves that we're "more" or "above" the animals. But we’re not. The evidence is in the way we hide our bodily functions and how we eat; hiding our animality is very apparent in things like "bathrooms," "plates, cups, forks, spoons, and tables," as well as "making toasts with drinks." Think about it. Observe other animals; how do they handle these functions and tasks?

These are all cultural constructs to help us disguise or hide our animal nature—you’ll never see other animals doing these things. We even disguise our food with names like "steak" or "hot dog." Those words have no real meaning as they apply to food. They are simply used to disguise what we’re doing.

We even disguise sex, the most animalistic behavior of all. We wrap it in "love" and make it something special, rather than simply acknowledging that it's an act of reproduction—an evolutionary drive just like survival. And we do it just like the rest of the animals. This is one of the reasons there are so many taboos, rituals, and rules around sex in different cultures. Ernest Becker said, “The distinctive human problem from time immemorial has been the need to spiritualize human life, to lift it onto a special immortal plane, beyond the cycles of life and death that characterize all other organisms. This is one of the reasons that sexuality has from the beginning been under taboos; it had to be lifted from the plane of physical fertilization to a spiritual one.”

Because of its animalistic nature, it’s an act that most reminds us of our mortality. That’s why we create all of the celebrations around it: flowers, chocolate hearts, “love letters,” fancy dinners, lingerie, holidays, etc. We want to elevate it as an act of “love” way beyond what the “animals” do; we make it “special” because we’re “special.”

It’s a difficult topic to unpack in the context of death anxiety. However, at its core, it reveals our animal nature and what we’ll devise in order to never face it or even admit what it really is.

“Yet, at the same time, as the Eastern sages also knew, man is a worm and food for worms. This is the paradox: he is out of nature and hopelessly in it; he is dual, up in the stars and yet housed in a heart-pumping, breath-gasping body that once belonged to a fish and still carries the gill-marks to prove it. His body is a material fleshy casing that is alien to him in many ways—the strangest and most repugnant way being that it aches and bleeds and will decay and die. Man is literally split in two: he has an awareness of his own splendid uniqueness in that he sticks out of nature with a towering majesty, and yet he goes back into the ground a few feet in order to blindly and dumbly rot and disappear forever. It is a terrifying dilemma to be in and to have to live with. The lower animals are, of course, spared this painful contradiction, as they lack a symbolic identity and the self-consciousness that goes with it. They merely act and move reflexively as they are driven by their instincts. If they pause at all, it is only a physical pause; inside they are anonymous, and even their faces have no name. They live in a world without time, pulsating, as it were, in a state of dumb being. This is what has made it so simple to shoot down whole herds of buffalo or elephants. The animals don't know that death is happening and continue grazing placidly while others drop alongside them. The knowledge of death is reflective and conceptual, and animals are spared it. They live and they disappear with the same thoughtlessness: a few minutes of fear, a few seconds of anguish, and it is over. But to live a whole lifetime with the fate of death haunting one's dreams and even the most sun-filled days—that's something else.” Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death

If we accept that we are animals, we are reminded that we will die and become “food for worms,” as Becker said—just like all of the other animals.

If you’ve seen the movie "Elephant Man," the line spoken by John Merrick really solidifies this idea. He said, "I am not an animal! I am a human being. I am a man." I know he was saying this in reference to his birth defect and appearance (the way he was being treated), but the argument still stands about how we feel about denying our animality and how insistent we are to separate ourselves from all other living things.

There can be a religious component to this belief. I understand why that is as well. In order to have the illusion of (literal) immortality, which we desire, there has to be something that sets us apart. Some religions even go as far as telling man to "take dominion over all living things and all of earth" (paraphrased). It’s easy to see how humans can believe that they are above other life. There’s another component to this: "Man was created in the image of God." This escalates into an even bigger problem. If you ask most religious people if they believe they’re an animal, they will say, "No, I’m special, created in the image of God; how could I be an animal?" This is what I was referring to in my post about Becker’s hero system. This is the religious component of that theory. It’s an effective illusion if one can maintain it. Both Friedrich Nietzsche and Ernest Becker believed that religion was no longer a valid hero system because of advances in science and technology, and because of these advances, most people have “moved on.” That’s where Nietzsche’s infamous quote came from: "God is dead." This was the idea behind it. Religion acted as a buffer against death anxiety for most people for thousands of years, all over the world, in all kinds of religions. In the last 200 years, we’ve become much more secular and tend to look to culture for our defense against death anxiety. Here again, you can see where we have denied our animality with these religious tenets—placing ourselves above every living thing and the earth itself.

What’s the caveat? What makes us different from animals? We have consciousness, or awareness, of our mortality. Your dog or cat doesn’t know that they’re going to die. They’re completely in the moment of “now.” There are no rabbits talking about being the best rabbit alive! Animals exist with instincts to survive and reproduce. At times, they may have the fight-or-flight instinct and be very afraid, but once out of danger, they never think about it again. In our unconscious mind, we are constantly in fight-or-flight mode. William James said, “There is always a panic rumbling beneath the surface of consciousness.” That panic comes from the knowledge of our impending death. Other animals don’t have this; that’s really the only thing that makes us different. It fascinates me to look at how we live and act, denying the inevitable (our death) and trying to hide the fact that we are animals. We would show our animality if we didn't have this knowledge. We would be exactly the same as all of the other animals.

I’m slowly, but surely, putting these pieces together. These are the pieces of these theories that show us who we are and why we are the way we are: human behavior. I’m specifically interested in the reasons we commit evil acts and how our death anxiety is revealed through acts of genocide, racism, bigotry, xenophobia, and “othering.” We have so much to learn about these topics. In the end, I hope to share a tiny piece about the role that art can play in disclosing ways to deal with these big topics.

“Denial of death, or, in psychodynamic terms, repression of death anxiety, generally results in banal and/or malignant outcomes—for example, preoccupation with shopping or the need to eradicate people who do not share our beliefs in a self-righteous quest to rid the world of evil. Repressed death anxiety is often projected onto other groups who are declared to be the all-encompassing repositories of evil and who must be destroyed so that life on earth will become what it is purported to be in heaven.”

Sheldon Solomon author of “The Worm at the Core: The Role of Death in Life

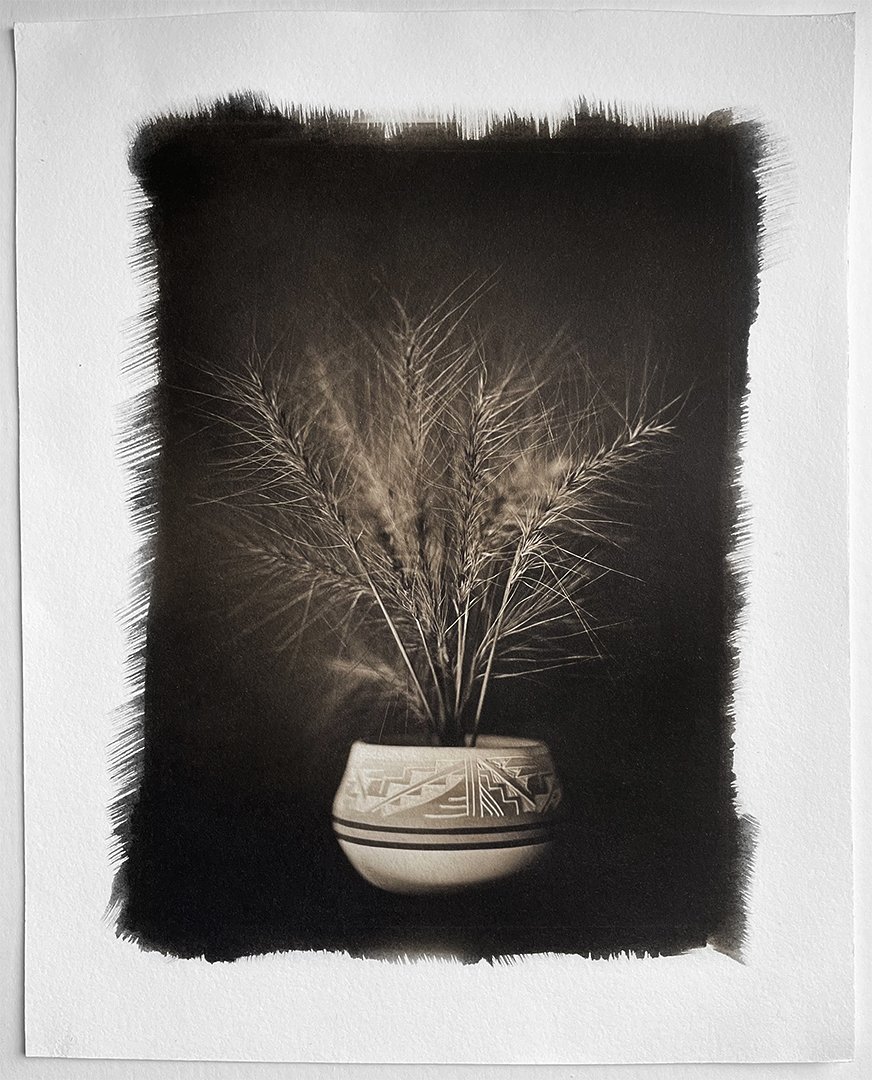

MEADOW BARLEY

The small grains are edible, and this plant was part of the Eastern Agricultural Complex of cultivated plants used in the pre-Columbian era by Native Americans.

Whole-plate palladiotype print from a wet collodion negative

I like how the brushstrokes of the palladium mimic the plant itself. I made this with an old Derogy lens wide open. For me, the falloff adds a lot of emotion and poetry.

Becker's Transference and Transcendence Theories

“The human animal is a beast that dies and if he's got money, he buys and buys and buys and I think the reason he buys everything he can buy is that in the back of his mind he has the crazy hope that one of his purchases will be life everlasting!”

― Tennessee Williams, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

Trained in cultural anthropology, Dr. Ernest Becker was motivated in his work by an overriding personal pursuit of the question, "What makes people act the way they do?" Refusing to dismiss answers to this question coming from any field of study based on empirical observation of human behavior, Becker almost inadvertently created a broadly interdisciplinary theory of human behavior that is neither simply speculative nor overly reductionist. Becker's synthesis, which is found in the title of his most famous book, "The Denial of Death," describes human behavioral psychology as the existential struggle of a self-aware species trying to deal with the knowledge of death.

Every day we are confronted with the reality of death and our own mortality. Simultaneously, we are strongly motivated by a survival instinct. Ernest Becker's existential psychological perspective came from this realization. His basic ideas have been largely substantiated in clinical testing conditions by a theory in social psychology called Terror Management Theory, created by American psychologists Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg, and Tom Pyszczynski. Their book, "The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life," provides the empirical evidence for Becker's theories.

Death is a complex struggle for human beings. The repressed (unconscious) knowledge of death keeps anxiety at bay and out of consciousness. We are born into culture, and the socialization process is largely one of learning how our culture symbolizes death. These cultural worldviews, as Becker calls them, are what we use to create the illusions we live in. The "urge to heroism," as he puts it, is what allows us to boost our self-esteem and manage our existential terror. In other words, our culture gives us opportunities, or not, to bolster our self-esteem, and in response, these illusions that our culture provides act as a buffer to our repressed knowledge of mortality.

How we symbolize death strongly impacts our sense of what the good life is and how we conceptualize the enemies (both personal and political) of ourselves and our society. Our culture's ways of heroically denying death and our habits of buffering ourselves too much or too little against the rush of death anxiety shape who we are as a society and as individuals.

As a symbolic defense against death, it's natural for people to try to ground themselves in powers bigger than themselves. It's also natural to feel attacked when our higher powers are taken away.

Freud coined the term "transference." He used it to describe a person, usually a client, transferring their feelings for another person to the therapist. In other words, the client may love their spouse, and during therapy, these feelings are "transferred" to the therapist.

Becker took this theory and applied it beyond the "client/therapist" model to almost anything. Human beings are constantly trying to mitigate their death anxiety. Using the terror management theory, they will "transfer" their love and admiration to an object in order to quell existential terror. This can be anything from a pair of tennis shoes to a religious deity.

After I read about this, I see it everywhere now. Sports teams, holidays, celebrities, cars, clothes, photography equipment—all of it seems to be used as transference objects. Because the majority of you who read these essays are photographers, I'd like to share one example from the world of photography.

Have you ever seen someone who gets a new (large format) camera and posts photographs of it? And, every now and then, a self-portrait with the camera? We’ve all done it. The bigger the camera or lens, the better. Most would apply Freud’s theory of compensation (sexual repression) to these images. In reality, Becker’s theory of transference applies here. It’s not sexual; it’s a transference object to stave off death anxiety. This can be applied, as I said before, to anything: clothes, boats, trucks, record players, computers, even spouses or significant others. Becker’s got an explanation for transference in humans; he concludes the segment with the fact that the partner worships the other person as a deity (think about the first dates) and then realizes that they have "clay feet." In other words, the transference eventually ends, and the spouse is seen as a mortal human that will eventually die.

Becker makes it very clear. We are temporarily relieved from the drag of "the animality that haunts our victory over decay and death." When we fall in love, we become immortal gods. But no relationship can bear the burden of godhood. Eventually, our gods and lovers will reveal their clay feet. It is, as someone once said, the "mortal collision between heaven and halitosis." For Becker, the reason is clear: "It is right at the heart of the paradox of man. Sex is of the body, and the body is of death. Let us linger on this for a moment because it is so central to the failure of romantic love as the solution to human problems and is so much a part of modern man’s frustrations."

Let me see if I can explain this as it relates to my work. This is another example of the way humans deal with the knowledge of their impending death and attempt to stave off the dread and fear of it. To me, it’s the most basic example of witnessing human behavior "in action" and quelling their existential dread. They don’t even know they’re doing it. It’s all unconscious behavior in service of repressing the knowledge of their mortality. These transference objects provide transcendence too. The person indulging feels "immortal" and is transcending death.

Human nature tends to lean toward the malignant manifestations of these theories. That’s what my work addresses: genocide, crimes against humanity, and "othering." Rather than using transference to tranquilize with the trivial, i.e., clothes, cars, lovers, drugs, shopping, TV, Facebook, and Twitter, some use human beings through violence and subjugation as transference objects.

Throughout history, we’ve seen human beings use "the other" to bolster their self-esteem and stave off death anxiety through torture, subjugation, and murder. That’s why, for me, it’s very important to understand these theories as they apply to the history of my work. The transference and transcendence theories are just more examples of the human condition. They answer, in part, the reasons for evil in the world.