Christine and John invited me to give a talk for their camera club. I gave an overview of my new book and shared a few images from it.

Proof Print of My New Book!

Photogenic Drawings

An example from my new book, “In the Shadow of Sun Mountain” pages 251-252:

“Rocky Mountain Cotton On Vellum Paper”

This image really speaks to the heart of what I’m exploring about mortality and artistic process.

The Talbotype process creates this direct indexical relationship between the object and its representation—the Rocky Mountain cotton literally left its shadow on the paper, what you might call a kind of death mask of the plant. This connects powerfully to what Becker writes about our need to leave traces of ourselves behind.

The luminous quality of the cotton head against that deep, velvety darkness reminds me of what Terror Management Theory describes as our attempts to create permanence from impermanence.

By using Talbot’s historical process, I’m not just capturing an image – I’m participating in a kind of photographic immortality project that spans nearly two centuries. The plant’s physical contact with the paper creates what we might call a “presence of absence.”

What fascinates me most is how this process makes visible something I’m deeply exploring in this book – the way artists transform ephemeral moments into lasting artifacts. The cotton’s delicate structure, rendered in this ghostly white against the dark ground, becomes both a document of its physical existence and a meditation on its transcendence through art.

The fact that this image was created through direct sunlight adds another layer of meaning—it’s as if nature itself is participating in this act of preservation. The process captures not just the form of the cotton but something of its essence, its being-in-time.

This relates directly to how I think artists process mortality differently—we’re not just recording death, we’re transforming it into something luminous and enduring.

Photogenic Drawings

As a visual artist exploring mortality and creativity, I'm fascinated by how Talbot's early photographic experiments mirror our human desire to capture and preserve moments against the inevitable flow of time. In 1834, five years before photography was officially announced to the world, William Henry Fox Talbot began his quest to record nature's fleeting images. His work wasn't just about technical innovation—it was about our deep-seated need to hold onto the ephemeral.

What draws me to Talbot's process is its raw intimacy with light and shadow, life and death. He called these camera-less images "photogenic drawings" drawings"—drawings born from light itself. The process feels almost alchemical: paper baptized in sodium chloride, anointed with silver nitrate that darkens like aging skin in the sun. When he laid objects—delicate botanical specimens or intricate lace—on this sensitized surface, he was essentially creating shadows, preserving the ghost prints of these items in negative space. Where light touched, darkness bloomed; where objects blocked the light, whiteness remained.

The resulting images were fragile, temporary—not yet truly "fixed" in photographic terms, but stabilized in a salt solution. Like our own attempts at immortality through art, they existed in a transitional space between permanence and fade. Talbot's preference for recording delicate, intricate patterns in nature speaks to me of our attempt to capture beauty before it withers, to hold onto the detailed texture of existence before it slips away.

His negative-to-positive process, which became the foundation for photography throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, fundamentally changed how we preserve our memories, our faces, and our moments of being. In doing so, it transformed how we negotiate with our own mortality.

Book cover of “In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of Othering and the Origins of Evil” 2025.

Blurb and Cover for My New Book

Through four years of living in the shadow of Sun Mountain (Tava-Kavvi) on ancestral Nuuchiu (Ute) lands in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, artist Quinn Jacobson confronts humanity's deepest psychological armor: our denial of death.

Using historical photographic processes and contemporary painting, he excavates the hidden forces behind cultural violence, erasure, and our desperate attempts at immortality.

Internationally renowned for reviving 19th-century wet plate collodion techniques, Jacobson merges this haunting medium with terror management theory and the writings of Ernest Becker to explore how death anxiety shapes human behavior.

Through his intimate collaboration with the mountain's landscapes, sacred plants, and symbols, he reveals both the wounds of colonization and possibilities for healing through artistic creation.

In the Shadow of Sun Mountain is a raw meditation on mortality, creativity, and the stories we tell ourselves to keep darkness at bay.

More than an artist's memoir, it is an invitation to confront the universal truth that shapes every human life: our shared impermanence.

“Baby Ponderosa Pine,” 8.5” x 6.5” (Whole Plate) POP Print from a wet collodion negative. I really like this image. I made the negative early in the morning in the summer time. The light from the east was just starting to peer over Sun Mountain. It’s such a perfect metaphor for what I’ve written about in my book. I titled my book “In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of Othering and the Origins of Evil” for this reason; all of the photographs I made for the project were (literally) made in the shadow of the mountain. It’s a great metaphor for both the historical events that took place here and the theories I’ve used as my foundation for the work.

Editing Artwork For My Book

Writing is an exercise in balance. It's the skill of retaining a reader's interest for an extended period, guiding them through the intricacies of your story. And let’s be honest—it’s hard to do well.

As a visual artist, I’ve spent years working in mediums I deeply understand: photography and visual arts. Writing, though? That’s a newer addition to my creative repertoire. Am I a writer? Maybe. Ask me again after you’ve read my book. For now, I’ll say this: I’m proud of the work I’ve done, but I’m acutely aware of the challenges. Writing isn’t about grammar or structure alone—it’s about connection. It’s about creating something that resonates, that lingers. Time will be the judge of whether I’ve succeeded.

In contrast, when it comes to visual art, I know my footing. I’ve spent decades refining my craft, immersed in observation, thought, and exploration. Despite my confidence, I find myself at a crucial juncture. I’m editing the visuals for my book—selecting which photographs and artworks will make it to print. The process is as exciting as it is painstaking. With over 200 pieces to choose from, I’m paring it down to 50, maybe 75. Every cut feels like a sacrifice.

How do I choose? For me, it’s all about context—how each image aligns with the narrative. The connection between the visuals and the text has to be seamless. Every photograph, every piece of artwork, must do more than look beautiful; it must amplify the story, offering a lens into its deeper layers.

This process reminds me of something essential: storytelling, whether through words or images, isn’t about showing everything—it’s about showing the right things. It’s about creating space for meaning, for resonance. And if I can do that, then maybe—just maybe—I’ll have a successful piece of work.

I still remember the first time I encountered the term homo narrans. The idea struck me immediately: storytelling, not language or reasoning, is what sets humans apart from other species. It suggests that we make decisions based on the coherence of stories rather than cold, hard logic. That resonates deeply with me. Storytelling isn’t just something we do—it’s how we make sense of our world, how we uncover meaning, and how we better understand ourselves.

Humans, though, carry an extraordinary burden. We’re the only creatures who know we’re alive and, someday, will die. That knowledge—whether we admit it or not—is crushing. Most of us suppress it, carrying the weight unconsciously. But it shows up, often in destructive ways, shaping our behavior and relationships in ways we don’t always recognize.

I see it every day. People walking around, bogged down by what some thinkers call the "overabundance of consciousness." There’s even a theory that our awareness of mortality—our recognition of death—was an evolutionary misstep. It’s hard not to feel that sometimes. But I also know this: if we hadn’t evolved the ability to deny and distort the reality of death, we wouldn’t have survived. That’s clear to me. Fear would have paralyzed us, kept us from taking risks, from facing danger, from living.

Think about it. We drive cars, walk across busy streets, play contact sports—all things that carry real risk. If we were constantly aware of what could go wrong, we’d be immobilized. And in our younger years, we pushed those limits even further. Some of us didn’t make it. I’ve written about those moments—stories of risk-taking and the tragic outcomes they sometimes led to. And yet, we still carry on, fueled by the unspoken belief: it won’t happen to me. That denial is what makes action possible, what allows us to survive, even thrive.

This dynamic fascinates me. The way we navigate mortality—the lies we tell ourselves, the unconscious bargains we strike—is at the heart of what it means to be human. As I’ve studied these ideas, I’ve come to understand just how central this denial is to our survival. It’s a feature of our evolution, not a flaw.

I’m excited to see these ideas come to life in my book. If you're interested, stay tuned to this blog for updates on its release date. I’m still deciding the best format: hardcover, softcover, audiobook, Kindle? Maybe all of the above. Stay tuned. It’s coming soon.

The 24-year-old Quinn in Mazatlan, Mexico, November 1988. Yes, that’s a 10,000 peso bill. The exchange rate was 2,600 Mexican pesos to 1 U.S. dollar. Today, it’s about 20 pesos to the dollar. That bill was worth about $4 USD at that time and almost $500 USD today. Perspective. Read the story about what happened to my friend on this trip (below).

Writing My Book and Telling My Stories

“In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of Othering and the Origins of Evil”

I wanted to share an update about my book. I’m excited about it!

I devote daily time to writing, reading, researching, making art, and most of all, thinking.

So far, my book breaks down something like this:

1

Introduction and Artist Statement

This chapter sets the stage for the book, explaining its purpose and relevance. It addresses some key questions. What is the book about, and why should a person read it? I introduce the themes, goals, and personal motivations driving this work. I also include my artist statement. It lays the foundation for the art itself, both technically and conceptually.

2

A Phenomenological Autobiography

Through personal stories, I explore how my life experiences have shaped my creative journey. This chapter demonstrates the deep connection between my artistic drive and the existential questions addressed by Becker's theories and Terror Management Theory (TMT). By connecting my own narrative to these frameworks, I provide insight into how creativity becomes a response to death anxiety or existential anxiety.

3

Ernest Becker

In this chapter, I delve into Becker’s groundbreaking theories, the denial of death and death anxiety. I supplement these with insights from anthropology, psychology, philosophy, theology, and art. I explain Becker's concept of the origins of evil, examining its definition and mechanisms, and scrutinizing the frequent attempts by humanity to eradicate perceived evil through acts of evil, using violence and dehumanization (oh, the irony!).

4

Terror Management Theory (TMT)

This chapter focuses on TMT and its relationship to Becker’s ideas, with a specific case study: the Tabeguache Ute Indians. I analyze how European colonizers used othering (Manifest Destiny) to justify acts of genocide and ethnocide against Native Americans, demonstrating the devastating consequences of existential anxiety, or death anxiety, on human behavior.

5

Artwork

Here, I present the artistic creations inspired by the concepts discussed in the previous chapters. This section ties theory and practice together, showing how my work embodies these existential and psychological themes. This chapter includes over a hundred photographic prints, paintings, and other visual media.

6

Essays

This chapter is a collection of essays I’ve written over the years, covering a range of topics from art and photography to philosophy and psychology. Along the way, you’ll find reviews and reflections on obscure ideas and peculiar subjects. The essays vary in length—some are just a few hundred words, while others span a couple of thousand. Their styles differ as well; some are explanatory, while others read more like personal journal entries.

Working It Out

It’s been a little over three years since I began writing this book and making art for it. In that time I’ve made considerable progress.

I’ve created a significant body of artwork, including the photographic prints for the book and several paintings. It has been an exciting journey, and I want to share it with those who have an interest in these theories and my work.

Drawing from the theories of Ernest Becker, Otto Rank, Terror Management Theory (TMT), and many others, I’ve used my personal experiences as a lens to investigate these existential questions. The work explores the psychology of othering, particularly through the historical lens of the Tabeguache Ute in Colorado, and delves into the roots of human evil—specifically, why people often mistreat those whose beliefs differ from their own.

I’ve been pleasantly surprised by how much I’ve enjoyed the writing process. It’s offered me profound insights into my identity and life experiences in ways I didn’t expect. Unlike photography, which captures a moment instantly, writing feels more akin to painting—it’s a slower, layered process. It generates ideas gradually, piece by piece, over time. This slower rhythm has been deeply rewarding, allowing ideas to mature and take shape in ways that feel both deliberate and organic.

A Tiny Preview of Some of My Stories

Jeanne and I spent the past week watching a Spanish series about a man who inherits the gift of premonitions from his mother. The story was intriguing and kept us engaged—it turned out to be a pretty enjoyable watch overall.

Watching it brought back memories of a trip I took to Mexico 36 years ago (see photo above). A group of friends traveled to Mazatlán, Mexico, to get out of the cold for a week—it was November 1988. One of our friends had a complete mental breakdown—he went into full-blown psychosis—at the end of the trip. It didn’t start until we were on the way home. The event lasted for several days. Like scenes from a horror film, I witnessed all of it firsthand. He ended up in a psychiatric hospital.

What happened? He went out one night with some locals—just two nights before the end of our trip. I tried to stop him but I couldn’t. He told me later that it involved methamphetamine, cocaine, and the Sinaloa Cartel (Cártel de Sinaloa).

What happened was surreal, a lot like the series we just watched. It prompted me to write about the experience in detail. I've come to understand that these kinds of experiences shaped both my creative life and my life in general. It’s like a long movie plot unfolding before me—the narrative arc—the more we observe, the more it reveals about who we are.

What I thought would never be relevant is central or key now to telling my story and the story of these theories I’m preoccupied with. In a lot of ways, it all fits together.

This story is in the second chapter of my book, which has about 15,000+ words so far and focuses on my family and friends. They are, in large part, the people who made me who I am.

From a young age, I was acutely aware of death—through tragic accidents, murder, suicide, drug addiction, war, and mental illness. These harsh realities seemed to loom around me. However, positive influences and uplifting experiences also surrounded me, shaping my early years.

The stories of my life begin around the age of eight and continue to the present day. I share memories of my mother, her deep love for humanity, and the lifelong battle she faced with mental illness. I also reflect on my grandmother’s fierce indignation whenever she heard racial slurs or witnessed people belittling those who were different. I’m so grateful for both of them.

I recount our family Thanksgiving dinners, where my mother would invite young men from the local Job Corps—African American, Native American, and Mexican American—making them welcome at our table every year. Our neighbors often didn’t know what to make of her; she was a profoundly progressive person, far ahead of her time.

One of the early stories recounts my heroin-addicted brother’s return from the Vietnam War. I write about the experience of traveling with my mother to the airport to pick him up. I’ve also written about my own experiences in the military, ten years after that, and the struggles I faced in its aftermath.

My writing delves into my time photographing dead bodies—gunshot wounds to the head, etc.—and the profound psychological impact it left on me.

I explore themes of drug use and overdoses, which have been a recurring presence in my life—friends and family dying from this kind of stuff. Most recently, my 61-year-old brother died in 2023 of methamphetamine toxcity. Alcohol and drug use was everywhere around me most of my life.

I witnessed a friend of mine shoot up Jack Daniels—yes, Jack Daniels, the whiskey. And yes, he put a needle in his arm and shot a syringe full of it into his vein. It was four o'clock in the morning—the party was still going, but there wasn’t any more cocaine available for him to shoot, snort, or smoke. I write about what he said, what he felt, etc. We gave him the nickname “Whiskey Pig” after that.

A few years later, his younger brother died of a drug overdose. During a lunch break from work, he bought some dope. He stopped at a red light in the middle of the city and injected the fentanyl-laced heroin he had just purchased. The dose was lethal—he died instantly, slumped over the steering wheel with the needle still in his arm.

These stories are my way of confronting those experiences and connecting them to the universal human search for meaning and the existential struggles that we all face. I explain how they have driven my creative life and the questions around existence.

My life is full of story after story about the struggles to exist—to cope with meaninglessness and insignificance. I’m sure I’m not the only one that could tell stories like these. However, they are uniquely mine and contrasted against the philosophical and psychological ideas around our existential struggles.

Isn't this the fundamental essence of existentialism? We are inherently searching for meaning in our lives when there is none. We crave significance and some kind of immortality that doesn’t exist. We lie and deny. We use our culture to provide meaning for us—we tranquilize ourselves with drugs, alcohol, shopping, fantasies, social media, fame, ideologies (religion, politics), or whatever can fill the void that faces us—mortality. It’s so clear to me.

Cultural constructs shape humanity, in my opinion. To me, most people are cuturally constructed meat puppets. Most people seem to be unaware of the importance of directly confronting and addressing the fundamental lie of existence—their mortality—and the consequences that ensue when they fail to do so.

That’s the theory of my book.

“In the City of Crosses” - April 27, 2024

Agreed Madness

It’s our “one month” anniversary today. We’ve been in New Mexico for 30 days, and man, time has whizzed by!!

Between unpacking boxes and running household errands, I’ve been slowly getting back on track to work on my book. I get excited about the thought of actually completing this work. It’s no longer a hope or dream; it’s close to becoming a reality.

“Man literally drives himself into a blind obliviousness with social games, psychological tricks, and personal preoccupations so far removed from the reality of his situation that they are forms of madness—agreed madness, shared madness, disguised and dignified madness, but madness all the same.”

These theories seem simple on the surface, but it takes some deep thinking and evaluation to really understand them and, moreover, to apply them to your life. My hope is that by sharing these ideas and concepts in a book, it will inspire people (especially artists) to engage with these theories and start to share them through their art.

I wrote a while ago about someone asking me if there was a movement in art around “death anxiety.” In other words, Becker’s and Solomon's (et al.) theories could form an entire art movement based on the theories dealing with death anxiety and terror management. This is what happened in existential psychology. There are people working on PhDs in terror management theory and have been for years; why not art? Not unlike impressionism, cubism, dada, etc.

In a lot of ways, all art does address these ideas, but rarely intentionally or consciously. It’s food for thought and a wonderful way to get people to engage with these ideas.

Importance of Creativity

"Both the artist and the neurotic bite off more than they can chew, but the artist spews it back out again and chews it over in an objectified way, as an external, active, work project. The neurotic can’t marshal this creative response embodied in a specific work, and so he chokes on his introversions.

The only way to work on perfection is in the form of an objective work that is fully under your control and is perfectible in some real ways. Either you eat up yourself and others around you, trying for perfection; or you objectify that imperfection in a work, on which you then unleash your creative powers. In this sense, some kind of objective creativity is the only answer man has to the problem of life.

The creative person becomes, in art, literature, and religion, the mediator of natural terror and the indicator of a new way to triumph over it. He reveals the darkness and the dread of the human condition and fabricates a new symbolic transcendence over it. This has been the function of the creative deviant from the shamans through Shakespeare.

Otto Rank asked why the artist so often avoids clinical neurosis when he is so much a candidate for it because of his vivid imagination, his openness to the finest and broadest aspects of experience, and his isolation from the cultural world-view that satisfies everyone else. The answer is that he takes in the world, but instead of being oppressed by it, he reworks it in his own personality and recreates it in the work of art. The neurotic is precisely the one who cannot create." Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death

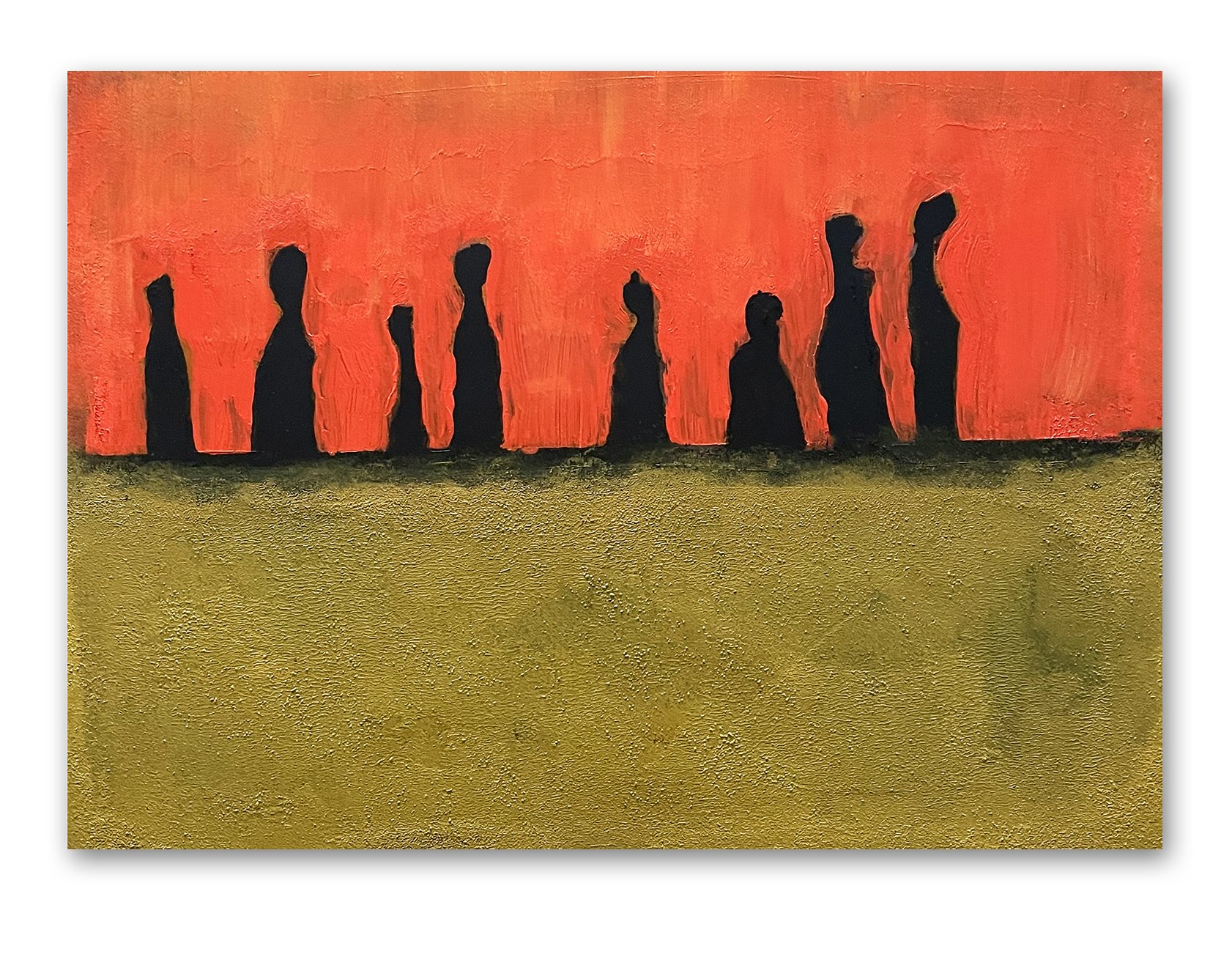

“Big Changes,” 3.75” x 5” acrylic, charcoal, newsprint (mixed media).

Radical Mindfulness Why Transforming Fear of Death is Politically Vital

This is a book by Dr. James Rowe that I would recommend reading if you want to understand what I’m trying to address through my artwork and my life in general (my interests). He is addressing Ernest Becker’s theories and terror management directly. I’ve never seen anyone write about the results of death anxiety applied to politics and modern and historical problems directly. My book will address these theories in detail, but I’ve made it personal. I’ve explained how the theories have driven me both creatively and psychologically.

Radical Mindfulness examines the root causes of injustice, asking why inequalities along the lines of race, class, gender, and species continue to exist. Specifically, Dr. James K. Rowe examines fear of death as a root cause of systemic inequalities and proposes a more embodied approach to social change as a solution.

Collecting insights from powerful thinkers across multiple traditions—including black radicals, Indigenous resurgence theorists, terror management theorists, and Buddhist feminists—Rowe argues for the political importance of seemingly apolitical practices such as meditation and ritual. These tactics are insufficient on their own, but when included in social movements fighting structural injustices, mind-body practices can start to transform the embodied fears that give supremacist ideologies endless fuel while remaining unaffected by most political actors.

Radical Mindfulness is for academics, activists, and individuals who want to overcome supremacy of all kinds but are struggling to understand and develop methods for attacking it at its roots.

“The Colorado Rocky Mountains,” 18” x 18” (45,72cm x 45,72cm) mixed media (acrylic, modeling paste, and resin) on canvas, September, 2023

Updates and News

Greetings. I have been “absent” online for the past couple of months for a variety of reasons. I wanted to post an update and share some news and let you know what’s happened.

First, I want to thank the people who have reached out to me by phone, text, email, or message. I appreciate that. Very kind. All is well; I’ve just had some events and a change of mind in how I want to communicate, or not, about my life and goings on.

DEATHS IN MY FAMILY

In August, my brother died from drugs. He was only 61 years old, but he had a long history of drug abuse and a troubled life, to say the least. It was shocking to hear the news, but not surprising in a lot of ways. Thirty days later, my father died of cancer. He’d been in hospice care for over a year and was quite ill. His death wasn’t as shocking but still a loss. They both died at home. So I’ve been taking care of all of that for the past 6–8 weeks, and it’s still going on, but I can see the end and closure at this point.

“On the Edge of a Precipice,” 9” x 12” (22,86cm x 30,48cm) Acrylic Painting, September 4, 2023

For the past five years, my studies in death anxiety, the denial of death, and terror management theory have really helped me process all of this. I don’t look at death the same way I once did. Yes, it’s sad; it's a loss, but coming to terms with the inevitable is reassuring and comforting. The Buddhists talk about attachment as suffering. I can see that; I understand the reasoning. Everything and everyone you know will be gone one day. All living things will die. Few think about it in those terms. I’m not saying we shouldn’t have attachments; we all do, but maybe think about the impermanence of everything. Try to see connectedness in a different way. I take great comfort in thinking about my “cosmic insignificance.” It puts my ego in check and helps me maintain psychological equanimity. I see so many people “inflated” about who they are or their "achievements,” and all I can think of is how misguided and diluted they are. I don’t want to use the word narcissist, but it’s very close to that. I understand why they do it; I understand Becker’s work and Solomon’s too.

The lack of self-awareness and self-refection is obvious. If there is one thing I would say to people like that, it is: “You have to come to terms with the fact that no one cares about what you do. No one.” The sooner you realize this, the sooner you can get on with really living life. It’s important for us to feel like we have value in a meaningful world. I don’t think that approach is the most healthy. If you’re an artist, make the work because you’re compelled or driven, not because you get “likes” or money from it. Think in terms of meaning and value. Try to see the world in a less self-centered way—less navel gazing and more cosmic insignificance! That’s been my goal for a while.

SOCIAL MEDIA

I’ve found myself more and more turned off by all of it. I’ve lost interest in it, to be honest. A few months ago, I started painting and doing some mixed media work for my book and didn’t want to share any of it on social media. We share too much. It’s overkill. I find myself disinterested in what people are doing because so many of them are doing the same thing. And everything seems to have a commercial objective to it—all about the money—very little about creativity or expression. I have no interest in commercial work. I know people have to make a living, or try, so I get that, but capitalism and creativity are like oil and water to me. So, I’ve stepped back from posting or interacting that way. Rick Rubin said in his book, The Creative Act: A Way of Being, “As artists, we seek to restore our childlike perception: a more innocent state of wonder and appreciation not tethered to utility or survival.“ That’s exactly how I feel about it. The caveat is that I will post some blog links on Instagram, but that’s about it.

“On the Edge of a Precipice #2,” 9” x 12” (22,86cm x 30,48cm) Acrylic Painting, September 19, 2023

I’ll continue to post here; as I move through my project, I’ll share some things, ideas, and progress. I will save a lot for the book. I like the idea of the book containing images and ideas that are only published there, not online. Currently, I’m still writing, editing, and making work. As I said, I’ve been doing some painting and mixed-media work. I’m allowing this to unfold however it wants. Another thing about working in solitude (not sharing everything) is that the external becomes silent and the internal can come forward. It’s powerful. I think technology has taken us captive (social media) and made us slaves to sharing everything we do, allowing the influence of strangers to guide and influence our work in a negative, non-personal way. That’s not a good thing. Again, Rick Rubin sums it up well. He said, “Art is choosing to do something skillfully, caring about the details, and bringing all of yourself to make the finest work you can. It is beyond ego, vanity, self-glorification, and the need for approval.” (The Creative Act: A Way of Being)

MAKING A MOVE

And last, but certainly not least, we’re thinking about relocating. We love it here, but as we get a bit older each year, we become more and more sensitive to the snow and cold. We want to live somewhere warm most of the year. Right now, we’re looking at Las Cruces, New Mexico. There are several reasons for this, but the main one is weather. Also, I want to be able to make art year-round; the weather plays a big part in that as well. We’re not sure when this will happen. Right now, the housing market is in trouble. We’re fine here; it's not a big deal if it takes some time. So, if you’re in the market for 12 acres of land and a new home in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, drop me a note (insert winky face here).

I hope you’re healthy and happy and find your center in this turbulent, chaotic world we live in. I wish you gratitude, awe, and humility in your daily life. Check back once in a while and you can see what I’m up to, and don’t be afraid to drop me a comment or an email-it’s always good to hear from my friends!

The Diversity in My New Book

In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of Othering and the Origins of Evil (expected to be published sometime in 2024)

You’re going to start seeing some "comps" posted here every once in a while. These are ideas that I have for my book. As I look through the images, some of the pairings absolutely astound me; they are more beautiful and aesthetically pleasing than I could have imagined.

I’m still undecided about how the final layout will look, but I wanted to play with mixing them up—POP with RA-4 color—living with them and running some ideas through my head. I think it looks stunning. I’ve never seen POP prints paired with Color Reversal Direct prints. Gorgeous!

Right now, it’s a 10” x 10” (25,4 x 25,4 cm) hardcover, full-color book. I expect it to be about 250 pages with over 100 images: RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Prints, Palladiotypes, Platinum-Palladium, Kallitypes (both K1 and K2 variants), Cyanotypes, Calotypes (Paper Negatives), Photogenic Drawings, and much more. The POP prints are from both wet and dry collodion as well as direct contact printing from plant material (photogenic drawings), like Salt prints.

“What do we mean by the lived truth of creation? We have to mean the world as it appears to men in a condition of relative unrepression; that is, as it would appear to creatures who assessed their true puniness in the face of the overwhelmingness and majesty of the universe, of the unspeakable miracle of even the single created object; as it probably appeared to the earliest men on the planet and to those extrasensitive types who have filled the roles of shaman, prophet, saint, poet, and artist. What is unique about their perception of reality is that it is alive to the panic inherent in creation.”

“The Great Mullein” Whole Plate Palladiotype from a wet collodion negative and a 10”” x 10” RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print

“Antlers Are Bone: Profile,” 10”” x 10” RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print, and “Mountain Stone Water Dish,” Whole Plate Palladiotype from a wet collodion negative.

“Three Aspens” Whole Plate Palladiotype from a wet collodion negative and “Ponderosa Pine and Five White Daisies” 10”” x 10” RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print

“Antlers Are Bone” Whole Plate Palladiotype from a wet collodion negative and a 10”” x 10” RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print

“Dead Ponderosa and Granite Rock Face” Whole Plate Palladiotype from a wet collodion negative and “Dead Daisies in a Glass Graduate," 10” x 10” RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print

“Red Rock Formation-Fremont County, Colorado,” a 10”” x 10” RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print and “The Great Aspen Man” Whole Plate Palladiotype from a Calotype (paper negative) Greenlaw’s process.

“Turkey Feathers and Antlers,” a 10”” x 10” RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print and “Medicine Wheel," a Whole Plate Palladiotype from a wet collodion negative.

“The Great Mullein,” a 10”” x 10” RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print and “Meadow Barley",” Whole Plate Photogenic Drawing from the plant itself (direct contact print).

A stack of prints—almost 200 prints—color, pop, calotypes (paper negatives), photogenic drawings, etc. And I still have about 3 months of image making left this year!