The Fragile Self Behind Big Achievements

What ambition reveals about death anxiety

The more I study Becker, the more I see how much of human insecurity comes down to one uncomfortable truth: most people are terrified of disappearing. They don’t usually say it that way. It comes out in softer language—ambition, legacy, accomplishment, contribution. But underneath those words is the ache Becker described so clearly: the fear of being insignificant in a world that will go on without us (Becker, 1973).

When I watch artists chase exhibitions, press coverage, museum collections, and permanent inclusion in the cultural record, I no longer read it as arrogance. I read it as fragility. I recognize the same existential wound I feel in myself when I’m honest. These gestures are attempts to fortify the self against erasure, to secure a foothold in history. They are ways of saying, “I was here. I mattered. I didn’t disappear without a trace.”

Becker understood this clearly. What looks like confidence from the outside is often a quiet negotiation with death. It’s a way of saying, “Something of me stays.” That longing comes straight out of what Becker called our need for heroism—the urge to feel like we matter in a universe that is largely indifferent to us (Becker, 1973).

What’s interesting is that this insecurity doesn’t look like insecurity. On the surface, it looks like confidence, drive, and success. Psychologically, though, achievement often becomes a proxy for survival. Terror Management Theory shows this with brutal clarity: when you remind people, even subtly, that they will die, they double down on whatever gives them a sense of meaning, status, or significance. They defend their worldviews more aggressively, seek more recognition, and cling harder to the systems that tell them they matter (Solomon, Greenberg, & Pyszczynski, 2015). Legacy becomes a way to negotiate with finitude rather than face it.

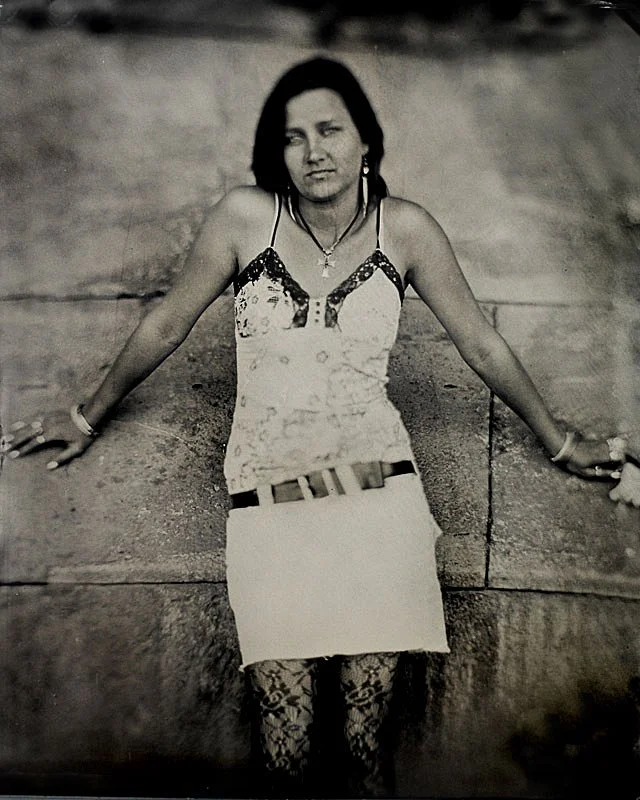

I see this constantly in the world I inhabit. The wet collodion community is a perfect example. On the surface, it’s about chemistry, craft, and technique—the miracle of coaxing an image out of silver and developer. But underneath, it carries the same existential insecurity that moves people everywhere else. There’s endless competition to appear more knowledgeable, more skilled, and more “authentic.” The constant stream of social media posts saying, “Look at me, I’m the best, I know the most about the process!” isn’t really about photography. It’s about being seen. It’s about proving you matter in a tiny world inside a vast, indifferent universe.

Technical mastery becomes another form of symbolic immortality. If I know the most, if I can produce the cleanest plates, if others admire my work or defer to my expertise, then maybe—just maybe—I won’t feel the tremor of my own impermanence for a moment. It’s the same psychology behind names on buildings and monuments, only expressed through a nineteenth-century photographic technique and the illusion that knowledge itself can make us safe. Underneath, it’s the same fear: if I’m not exceptional, I might vanish.

For years, I chased my own version of legacy without naming it. I wanted the exhibitions, the books, the mastery, and the recognition. I told myself it was about the work, and some of it truly was. But if I’m honest, part of it was the same old story. I wanted to leave a mark that might outlive me. I wanted to matter in a way the universe couldn’t erase.

That’s shifted for me. Not because I’ve outgrown ambition, but because I’ve faced the fact that none of it lasts. Even the most celebrated artists eventually fade. Even the most beautiful plate will tarnish, break, or disappear. Even the sharpest knowledge dulls when the next generation arrives. Mortality has a way of clearing the air.

I’ve come to see that symbolic immortality exists on a spectrum. Some people seek it through children. Others through service. Others through work or institutions. And some go very big, because the anxiety underneath is just as large. The louder the legacy project, the more fragile the self underneath it tends to be. The person isn’t trying to be admired. They’re trying to survive their own awareness of impermanence.

This is where my work as an artist diverges from these cultural immortality systems. Most people try to outlive death by attaching themselves to institutions or authority structures. In photography, that can mean trying to become the expert, the master, the one others look to as an anchor of certainty. Artists—at least those who confront mortality directly—metabolize that same fear through creation rather than performance. Art becomes a way to live with death instead of outrunning it.

One system says, “Remember me.”

The other says, “This is what it feels like to be mortal.”

That distinction is changing my practice. I’m not trying to build a monument to myself, inside or outside the collodion world. I’m trying to understand what it means to stand here for a moment, knowing the moment ends. Creativity, in that sense, isn’t a buffer. It’s a reckoning. It’s how I listen to the part of myself that knows I will die and give that knowledge form instead of choking on it. Art lets me leave a trace without pretending the trace is a cure for impermanence.

And now I want to turn the questions back to you, because Becker wasn’t writing about other people. He was writing about all of us.

What are you building to feel permanent?

Whose approval keeps you from feeling invisible?

What are you clinging to because the thought of disappearing feels unbearable?

What version of symbolic immortality are you chasing—career, legacy, reputation, mastery, certainty, perfection?

And maybe the most important question:

What would your life and your art look like if you stopped trying to outlive death and started learning how to live with it?

That’s the shift I’m making. I don’t know where it leads yet, but I can feel the work changing. My attention is moving from achievement to awareness, from legacy to presence, from performance to honesty. Maybe that’s its own kind of immortality—not the kind that gets your name on a building, but the kind that allows you to be fully alive in the time you have.

How the New Work Reflects This Shift

If you’ve been following my recent work—the figures, the new plates, the Sun Mountain project—you may have noticed the change before I did. The work isn’t trying to prove anything anymore. It isn’t trying to be perfect or technically untouchable. It isn’t even trying to last.

These pieces come from a different place. The clay figures, with their brittle limbs and suspended bodies, don’t posture for importance. They surrender. They acknowledge breakage. They know gravity always wins. They are small acts of honesty about what it means to be human.

The plates carry a different kind of imperfection now. The mottle marks, developer sweeps, and fogging—once treated as errors—feel more like evidence. Traces of a hand that doesn’t pretend it can control everything. Silver remembers everything, and lately I’m less interested in correcting that memory than in listening to it.

And Sun Mountain has been the biggest teacher. Photographing a place saturated with history, trauma, beauty, and silence forced me to encounter mortality not as an idea but as something lived. The land, the scars, the prayer trees—temporary, fragile, and somehow more meaningful because of that. Those images aren’t about legacy. They’re about witnessing.

This shift has changed my process. I no longer enter the studio or darkroom trying to outperform anyone—not myself, not the collodion community, not the ghosts of the masters. I enter trying to listen. To let the work unfold rather than force it into a monument.

If earlier years of my practice were about building a name, this chapter is about losing one. Letting the ego loosen. Letting the work breathe without the burden of permanence.

Maybe this is the quiet wisdom Becker gestured toward: when we stop trying to escape death, the art gets quieter and more honest. It stops reaching upward and starts reaching inward. And in that shift, something opens—not immortality, but meaning.

If You Think This Doesn’t Apply to You

Some people will read this and say, “I’m not doing that. I’m not chasing legacy. I don’t have death anxiety.” I get it. I used to say the same thing. Most of us do, because these defenses don’t feel like defenses. They feel like personality. Preference. “Just the way I am.”

The denial of death rarely announces itself. It works under the surface. Becker was blunt about this: the mechanisms we use to manage mortality awareness are almost always unconscious (Becker, 1973). Terror Management Theory confirms the same point. People can swear they’re unaffected by death, then shift their behavior the moment mortality becomes salient, without ever realizing why (Solomon et al., 2015).

So if you feel the instinct to say “not me,” pause and look a little closer.

Do you get irritated when someone challenges your beliefs?

Do you feel threatened when someone succeeds in a way you hoped to?

Do you rely on your role, talents, expertise, or identity to feel stable?

Do you need to be right? Respected? Seen?

Do you cling to certain narratives about yourself because losing them would feel like losing solid ground?

None of this means you’re weak. It means you’re human. Your psyche is doing exactly what it evolved to do: protect you from the unbearable fact that life ends and none of us controls the timing.

Understanding this didn’t make me ashamed. It made me awake. Gentler. Less judgmental of myself and others. Clarity, not legacy, is the beginning of meaning.

Closing Reflection

I’m no longer making work to prove I was here. I’m making work to understand what here even means. Becker helped me see that much of what I once called ambition was another shield against impermanence. Facing mortality—through theory, lived experience, and decades of practice—showed me that legacy was never the answer.

What I want now is quieter and more honest. Art that doesn’t try to outlive me but helps me live while I’m here.

I invite you to look at your own life with the same clarity. What are you building to avoid impermanence? What would your creative work, your relationships, and your sense of self look like if you stopped reaching for permanence and learned to stand inside the temporary?

That’s where the real transformation begins. Not in being remembered, but in finally being present.

References

Becker, E. (1973). The denial of death. Free Press.

Solomon, S., Greenberg, J., & Pyszczynski, T. (2015). The worm at the core: On the role of death in life. Random House.