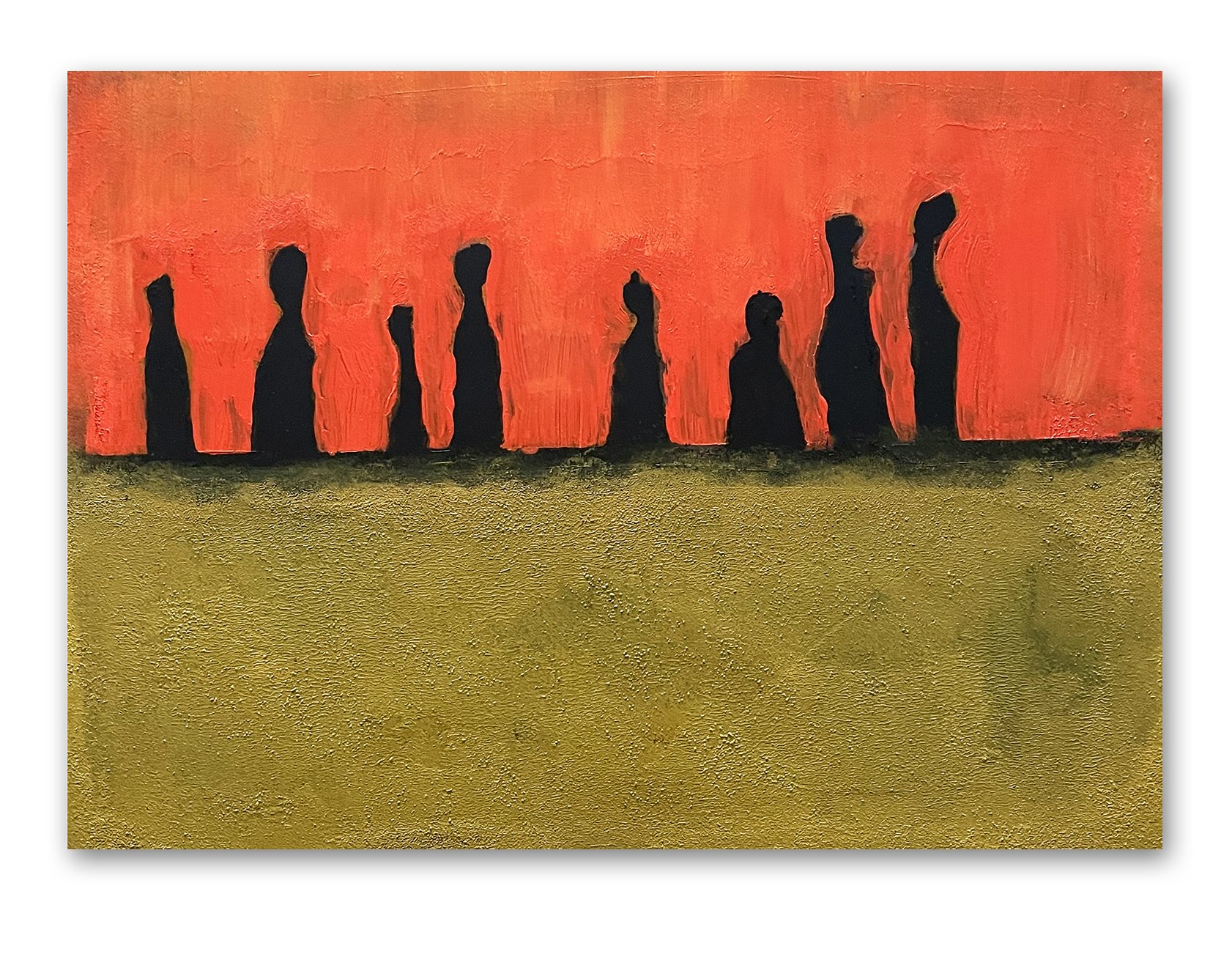

“Turquoise & Tissue,” 18” x 18” (45,72cm x 45,72cm) acrylic on canvas (with tissue paper base), September 2023

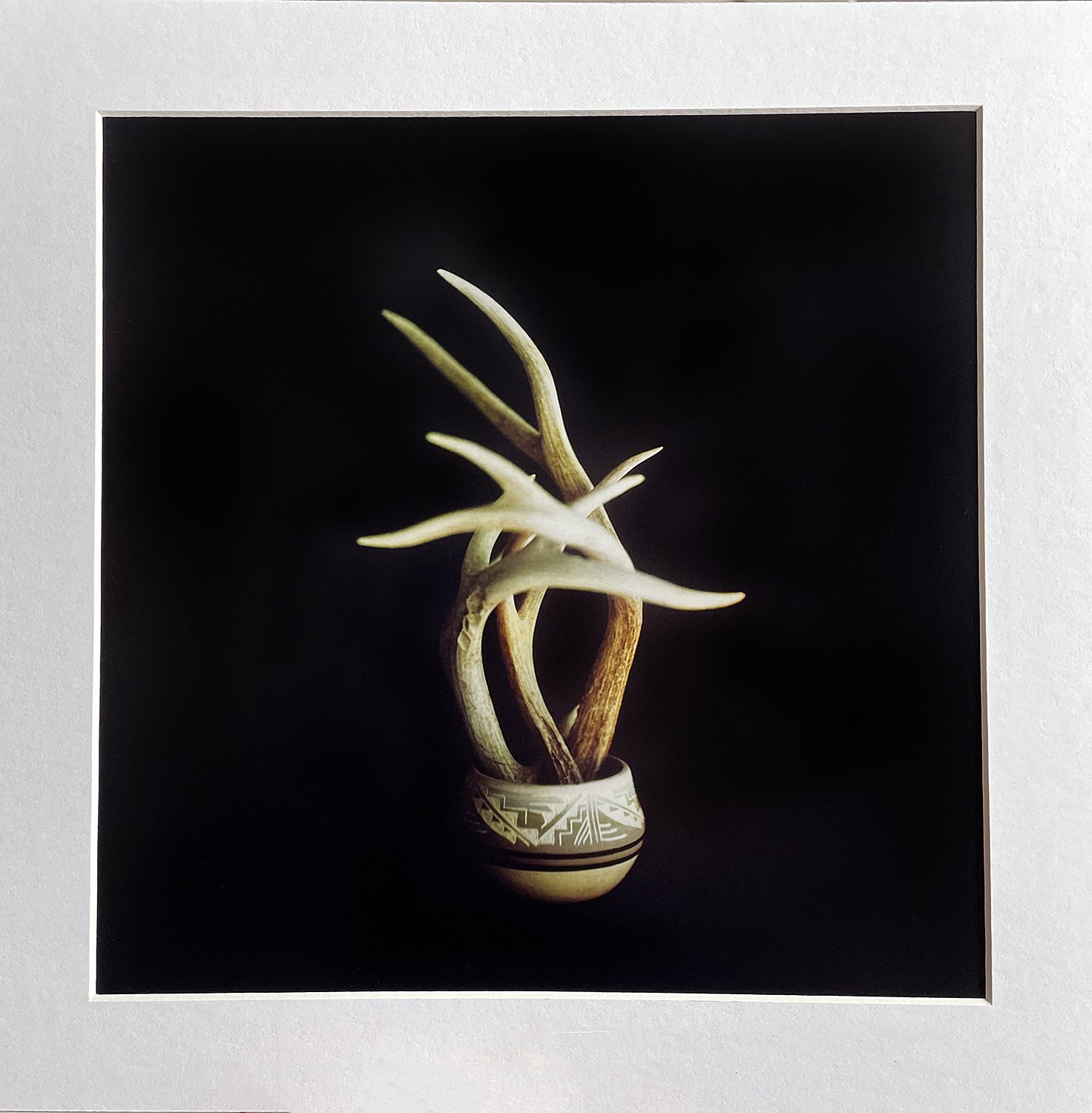

“Rocky Mountain Mule Deer Antlers,” 18” x 18” (45,72 x 45,72cm) Mixed Media: Photography, Painting, and Sculpting, August 20, 2023

Something New: Mixed Media; Photography, Painting, and Sculpting

A while ago, I decided I needed to take this work to the next level. I needed to address questions surrounding something “missing” in the work. I wrote an essay a few weeks ago about searching for words like “tactile” and “tangible,” as well as enhancing color—all in the service of decay and impermanence. I wanted to engage the work in an interdisciplinary way—deeper and more involved than simply looking at a photograph. I want to create something that asks to be touched and experienced beyond photography. My goal is to transcend photography and create a “living” piece of art that represents this land, the people that were here, and the theories I’m addressing surrounding all of it.

Colors and Textures: I’ve mimicked the colors of fall as well as the colors found in the antlers. The surface of the canvas is a reminder (in the shapes) of the antlers as well as roots or veins reaching into the earth. The colors and textures in this piece worked very well together. It is tactile, physical, and contains real objects from the land. The antlers on the canvas are the antlers (some of them) in the photograph. It’s also a reference to the Ute’s skillful tanning of buckskin (deer hides). They were known for the quality and beauty of the leather they made.

Canvas Choice (18” x 18" - 45,75 x 45,75cm): It’s simple; the canvas represents the shape of the state of Colorado. I did the same thing when I made the Ghost Dance work: 6” x 6” wet collodion negatives and prints. I just carried that concept over to this project.

Fibonacci Sequences: Living on this mountain for the past three years, I’ve become closer to nature. I go to bed when the sun sets, and I get up when it rises. I’m aware of the seasons like never before. I see plants and animals in all stages of their lives. The flow and balance of nature are both awe-inspiring and beautiful. I’m beyond grateful to have experienced this. I’ve spent a lot of time photographing flora. I can see the patterns and the consistency in them. I studied the Fibonacci sequence and became very interested in it. I’ve posted about it before. I’ve designed these mixed media pieces based on the Goldaen Ratio and Fibonacci sequences. This is the only time I’m going to point out the details in a piece. The photograph has 10 antler tips and 3 bases—that’s 13. The antlers and antler buttons surrounding the image represent the number 8. The layout is on the Golden Ratio grid. You get it.

Symbolism of Circles: The Tabeguache Ute always set up a medicine wheel, or the circle of life, at each camp when they traveled in the spring and fall. For them, it represents the continuous pattern of life and death, the paths of the sun and moon, as well as the shape of the earth and moon, among many other things. I’ve used the idea of circles as a way to recognize that and to give a sense of peering into something eternal yet impermanent—a visual paradox. The Circle of Life is a central theme of Ute life. The Ute people have a unique relationship with the land, plants, and all things living. The Circle of Life represents the unique relationship in its shape, colors, and reference to the number four, which represents ideas and qualities for the existence of life.

I found this in a presentation to Colorado 4th graders. The People of the early Ute Tribes lived a life in harmony with nature, each other, and all of life. The Circle of Life symbolizes all aspects of life. The Circle represents the Cycle of Life from birth to death for people, animals, all creatures, and plants. The early Tabegucahe Utes understood this cycle. They saw its reflection in all things. This brought them great wisdom and comfort. The Eagle is the spiritual guide of the People and of all things. Traditionally, the Eagle appears in the middle of the Circle.

The Circle is divided into four sections. In the Circle of Life, each section represents a season: spring is red, summer is yellow, fall is white, and winter is black. The Circle of Life joins together the seasonal cycles and the life cycles. Spring represents Infancy, a time of birth and newness—the time of “Spring Moon, Bear Goes Out.” Summer is Youth. This is a time of curiosity, dancing, and singing. Fall represents Adulthood, the time of manhood and womanhood. This is the time of harvesting and of change: “When Trees Turn Yellow” and “Falling Leaf Time.” Winter begins with gaining wisdom and knowledge about “Cold Weather Here.” Winter represents old age, a time to prepare for passing into the spirit world.

The Circle also symbolizes the annual journey of the People. On this journey, the People moved from their winter camp to the mountains in the spring. They followed trails known to each family group for generations. The People journeyed to each family group for generations. The People journeyed as the animals did. Following the snowmelt, they traveled up to their summer camps. In the fall, as the weather changed, the People began their journey back to their winter camps. Once again, they followed the animal migrations into lower elevations. They camped near streams, rivers, springs, and lakes. These regions provided winter shelter and warmth.

The early People carried with them an intricate knowledge of nature. They understood how to receive the rich and abundant gifts that the Earth, Sky, and Spirit provided. They also understood how to sustain these gifts. They took only what was needed. The People used the plants, animals, and earth wisely. They gave gifts in return. This knowledge was the People’s wealth.

The Circle of Life is the rich cultural and spiritual heritage of the Tabegucahe Ute. This heritage is still alive in the life cycle and seasonal cycles of today. It still is alive within the harmony of nature. It is reflected in the acknowledgement and practice of honoring and respecting all things, people, and relationships. The Circle design can be found on the back of traditionally made hand drums. These drums are important ceremonial instruments for the People today.

The idea of impermanence and decay plays a big role in my approach to this work. I've tried to develop a deeper appreciation of impermanence, specifically of my own impermanence. It’s important for me to try to make the viewer aware of their mortality through these pieces and the theories they’re based on. Everything I’ve made images of is either dead or changing in some way (entropy). The way I’m building these pieces up—the textures and colors—refers to the idea of both death and decay (impermanence) and life and living. An elevated sense of gratitude for every fleeting moment of life is very important to have. It fosters a significant recognition of the invaluable essence of human existence by observing the natural endings in everyday life, like leaves falling from trees or the decay of organic matter. This helps people connect with the concepts of impermanence and death on a smaller scale. That’s the big connection between my work and these theories.

I find myself contemplating compassion more while doing this work. Thinking about my own struggles with difference. I suppose the wonderful thing about learning about these theories (death anxiety and terror management theory) is that you have a lot of time to think about, or even meditate about, your own death and the deaths of loved ones. In turn, that allows you to come to terms, in some ways, with all of it. Moreover, I’ve found I have a heightened zest for life. A greater appreciation for the cycle of life, or, as the Tabeguache Ute would call it, the Circle of Life.

Currently working on monotypes: I’ve been working with acrylic paint and doing monotypes. I really like them; they have a lot of potential for this project. As time goes on, I’ll post some occasionally. I just wanted to share this mixed media idea I had and my thinking around it.

“The Colorado Rocky Mountains,” 18” x 18” (45,72cm x 45,72cm) mixed media (acrylic, modeling paste, and resin) on canvas, September, 2023

Updates and News

Greetings. I have been “absent” online for the past couple of months for a variety of reasons. I wanted to post an update and share some news and let you know what’s happened.

First, I want to thank the people who have reached out to me by phone, text, email, or message. I appreciate that. Very kind. All is well; I’ve just had some events and a change of mind in how I want to communicate, or not, about my life and goings on.

DEATHS IN MY FAMILY

In August, my brother died from drugs. He was only 61 years old, but he had a long history of drug abuse and a troubled life, to say the least. It was shocking to hear the news, but not surprising in a lot of ways. Thirty days later, my father died of cancer. He’d been in hospice care for over a year and was quite ill. His death wasn’t as shocking but still a loss. They both died at home. So I’ve been taking care of all of that for the past 6–8 weeks, and it’s still going on, but I can see the end and closure at this point.

“On the Edge of a Precipice,” 9” x 12” (22,86cm x 30,48cm) Acrylic Painting, September 4, 2023

For the past five years, my studies in death anxiety, the denial of death, and terror management theory have really helped me process all of this. I don’t look at death the same way I once did. Yes, it’s sad; it's a loss, but coming to terms with the inevitable is reassuring and comforting. The Buddhists talk about attachment as suffering. I can see that; I understand the reasoning. Everything and everyone you know will be gone one day. All living things will die. Few think about it in those terms. I’m not saying we shouldn’t have attachments; we all do, but maybe think about the impermanence of everything. Try to see connectedness in a different way. I take great comfort in thinking about my “cosmic insignificance.” It puts my ego in check and helps me maintain psychological equanimity. I see so many people “inflated” about who they are or their "achievements,” and all I can think of is how misguided and diluted they are. I don’t want to use the word narcissist, but it’s very close to that. I understand why they do it; I understand Becker’s work and Solomon’s too.

The lack of self-awareness and self-refection is obvious. If there is one thing I would say to people like that, it is: “You have to come to terms with the fact that no one cares about what you do. No one.” The sooner you realize this, the sooner you can get on with really living life. It’s important for us to feel like we have value in a meaningful world. I don’t think that approach is the most healthy. If you’re an artist, make the work because you’re compelled or driven, not because you get “likes” or money from it. Think in terms of meaning and value. Try to see the world in a less self-centered way—less navel gazing and more cosmic insignificance! That’s been my goal for a while.

SOCIAL MEDIA

I’ve found myself more and more turned off by all of it. I’ve lost interest in it, to be honest. A few months ago, I started painting and doing some mixed media work for my book and didn’t want to share any of it on social media. We share too much. It’s overkill. I find myself disinterested in what people are doing because so many of them are doing the same thing. And everything seems to have a commercial objective to it—all about the money—very little about creativity or expression. I have no interest in commercial work. I know people have to make a living, or try, so I get that, but capitalism and creativity are like oil and water to me. So, I’ve stepped back from posting or interacting that way. Rick Rubin said in his book, The Creative Act: A Way of Being, “As artists, we seek to restore our childlike perception: a more innocent state of wonder and appreciation not tethered to utility or survival.“ That’s exactly how I feel about it. The caveat is that I will post some blog links on Instagram, but that’s about it.

“On the Edge of a Precipice #2,” 9” x 12” (22,86cm x 30,48cm) Acrylic Painting, September 19, 2023

I’ll continue to post here; as I move through my project, I’ll share some things, ideas, and progress. I will save a lot for the book. I like the idea of the book containing images and ideas that are only published there, not online. Currently, I’m still writing, editing, and making work. As I said, I’ve been doing some painting and mixed-media work. I’m allowing this to unfold however it wants. Another thing about working in solitude (not sharing everything) is that the external becomes silent and the internal can come forward. It’s powerful. I think technology has taken us captive (social media) and made us slaves to sharing everything we do, allowing the influence of strangers to guide and influence our work in a negative, non-personal way. That’s not a good thing. Again, Rick Rubin sums it up well. He said, “Art is choosing to do something skillfully, caring about the details, and bringing all of yourself to make the finest work you can. It is beyond ego, vanity, self-glorification, and the need for approval.” (The Creative Act: A Way of Being)

MAKING A MOVE

And last, but certainly not least, we’re thinking about relocating. We love it here, but as we get a bit older each year, we become more and more sensitive to the snow and cold. We want to live somewhere warm most of the year. Right now, we’re looking at Las Cruces, New Mexico. There are several reasons for this, but the main one is weather. Also, I want to be able to make art year-round; the weather plays a big part in that as well. We’re not sure when this will happen. Right now, the housing market is in trouble. We’re fine here; it's not a big deal if it takes some time. So, if you’re in the market for 12 acres of land and a new home in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, drop me a note (insert winky face here).

I hope you’re healthy and happy and find your center in this turbulent, chaotic world we live in. I wish you gratitude, awe, and humility in your daily life. Check back once in a while and you can see what I’m up to, and don’t be afraid to drop me a comment or an email-it’s always good to hear from my friends!

“Leftovers: What’s Left Behind,” 10” x 10” (25,4 x 25,4 cm) RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print, August 27, 2023.

This is the first stage in the process: making the photograph. I’ve started doing mixed media pieces on 18” x 18” (45,72 x 45,72cm) canvas. I’m using photography, painting, and sculpture. At some point, I’ll share one or two pieces. Right now, I’m just excited to work through my ideas for a while.

I begin with a photograph, like this one, and use it as a starting point on the canvas-colors, textures, ideas, etc. I’m working in acrylics and making different types of sculptures from various materials. I’m using modeling paste and gesso for the textures and mixing different materials into that, mostly materials from the land.

I find incredible joy in working like this. It’s so satisfying and allows me to expand ideas and work in an interdisciplinary fashion. Like the theories I’m basing this work on, which are interdisciplinary, I find the connection to be powerful and very supportive.

The Act of Creating Art is Terror Management

“Man is literally split in two: he has an awareness of his own splendid uniqueness in that he sticks out of nature with a towering majesty, and yet he goes back into the ground a few feet in order to blindly and dumbly rot and disappear forever. It is a terrifying dilemma to be in and to have to live with.

Man has a symbolic identity that brings him sharply out of nature. He is a symbolic self, a creature with a name, a life history. He is a creator with a mind that soars out to speculate about atoms and infinity, who can place himself imaginatively at a point in space and contemplate bemusedly his own planet. This immense expansion, this dexterity, this ethereality, this self-consciousness gives to man literally the status of a small god in nature, as the Renaissance thinkers knew.

The knowledge of death is reflective and conceptual, and animals are spared it. They live and they disappear with the same thoughtlessness: a few minutes of fear, a few seconds of anguish, and it is over. But to live a whole lifetime with the fate of death haunting one’s dreams and even the most sun-filled days—that’s something else.”

THE MOST IMPORTANT QUESTIONS WE CAN ASK OURSELVES

What’s the most important question, or questions, that a human being can ask? Have you ever thought about that? I have. A lot. For me, and I believe for all humanity, the most important questions revolve around existence. Why am I here? What’s my purpose? Is there a meaning to life? If there is, what is it?

These are the questions that started me on my journey almost 40 years ago. For most of my life, I’ve used photography to explore these questions. Examining why some people are treated differently than others and pondering why the gulf between individuals exists. It was the beginning of my quest to understand what drives human behavior. There is the direct question of purpose, too. Religions were created to answer these questions, but they answer them based on faith, not empirical evidence. There’s evidence that the earliest homo sapiens invented and practiced some kind of religion. Humans have always depended on some kind of supernatural belief. Why is this? The answer is simple: to deal with the knowledge of death and quell the existential anxiety that arises from that knowledge. Death anxiety is a powerful driver in daily life, and most people never know that it is directing their lives. We do all kinds of things to distract ourselves from consciously thinking about our deaths. These distractions can be good or bad. Religions have been the main staple for staving off death anxiety for millennia. Things have changed in the last 300 years. The Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution (technology) have given rise to people leaving religion and leaning on new constructs to quell their death anxiety. This is why Friedrich Nietzsche said, “God is dead.” He was referring to technology, money, fame, etc., freedom from religion, and personal growth. A form of terror management.

Human beings have an unconscious desire for immortality. We simply can’t face the fact of death or non-existence; it’s what we fear most, whether we know it or not, and most don’t. Ernest Becker wrote, “Man is literally split in two: he has an awareness of his own splendid uniqueness in that he sticks out of nature with a towering majesty, and yet he goes back into the ground a few feet in order blindly and dumbly to rot and disappear forever”. This quote is from Becker's 1973 book, The Denial of Death.

Pessimistic philosophers would tell you that life is a mistake. The overabundance of consciousness (the knowledge of mortality) is an evolutionary misstep. Peter Zapfee talks about the “suffering of brotherhood,” saying that the true knowledge of how much pain and suffering there is in the world is unbearable. The "brotherhood of suffering" is a concept in The Last Messiah by Peter Wessel Zapffe. In the parable, a paralyzed hunter recognizes that the animal's fear and hunger are similar to his own. The hunter then feels a great psalm about the brotherhood of suffering among everything alive.

Zapffe believed that the human condition is tragically overdeveloped and that the world is beyond humanity's need for meaning. He viewed the world as unable to provide any answers to fundamental existential questions.

While I’m not a pessimist, I can see the value of arguments like Zapffe’s. There are no answers to these big questions. There are only distractions to keep us from thinking about them. That’s what terror management theory addresses. How we distract ourselves from the reality of living—that there is no meaning or purpose in life. And that we will die and be forgotten.

The illusions or cultural constructs (cultural worldviews) we lean on to quell our death anxiety are everywhere: religion, politics, having children, getting married, sports, money, fame, degrees, awards, jobs, social status, drugs, alcohol, shopping (tranquilizing with the trivial)—anything to bolster our self-esteem and keep the existential anxiety repressed—and it works, and it works well. If you spend any time on social media, you can easily spot what people rely on to buffer their anxiety. I’ve seen people deeply identify with their vehicles, photography achievements, how long they’ve been married, their new clothes and “look,” the celebrity they met or the concert they attended, and so many other (too much information) things that are meaningless and trivial. What they don’t understand is that no one really cares.

Humans have evolved to suppress or repress this knowledge—to distract ourselves and deny our mortality. We had to, or we wouldn’t have survived. I read a book a while ago called "Denial: Self-Deception, False Beliefs, and the Origins of the Human Mind" by Ajit Varki and Danny Brower. The book presents a theory on the origins of the human species. It explains why denial is a key to being human. The authors argue that humans separated themselves from other creatures because they became self-aware of their own and others' mortality. They then developed a way to deny that mortality. The book offers a warning about the dangers of our ability to ignore reality. It asks why other intelligent animals have not evolved like humans. The authors' answer is that humans have crossed a major psychological evolutionary barrier by developing the ability to deny reality. The theory of mind (TOM) plays a big role in this evolutionary step. I highly recommend reading the book.

Where does that leave us? Well, for some of us who don’t lean on some of the aforementioned illusions, there is art. Art is our distraction and our buffer. The coping mechanism we use to repress the knowledge of our deaths works well. It gives us meaning and significance and makes us feel like we are part of something bigger than ourselves—that maybe our art will live on after we are gone (symbolic immortality). Regardless of what we do, what we create, or where it ends up or not, the function of art is an important one.

WHY DO WE MAKE ART?

No one is going to save the world by making art. That’s not difficult to understand, and I think we can all agree on that. However, living a creative life can bring peace and satisfaction. And it can bolster your self-esteem. That’s really the function of art. It’s to allow creative people to transfer their existential anxiety onto an object (sublimation), into music, or onto a written page. I’ll talk more about this in a minute. So, we make art to keep our neurosis in check. To bring us meaning and significance and to quell our death anxiety. That’s the function of art. And if people like it after all of that, great! But that’s not the reason or function of art.

THE TWO THINGS THAT I HAVE GREAT CONFIDENCE IN SAYING ARE TRUE

I’ve studied the theories of Ernest Becker, Solomon, et al. (TMT) since 2018. And for the past two years, I’ve engaged with these ideas more deeply than I ever have before. Through these studies, I’m convinced of a couple of things.

CREATING ART IS TERROR MANAGEMENT

First, creating art is done in the service of terror management (TMT). One of the ubiquitous characteristics of human art throughout history and across cultures is the attempt to come to terms with mortality and achieve symbolic forms of immortality. In essence, saying, “I was here” or “remember me!” And the act itself buffers our existential dread. I’m convinced of that. There have been many philosophers, even beyond Becker, who have eluded to this. Peter Zapfee called in sublimation. He said it was the best form of terror management, but few people could do it. He wrote in his essay, The Last Messiah (1933), "Sublimation is the refocusing of energy away from negative outlets toward positive ones. Through stylistic or artistic gifts, the very pain of living can sometimes be converted into valuable experiences. Positive impulses engage the evil and put it to their own ends, fastening onto its pictorial, dramatic, heroic, lyric, or even comic aspects. To write a tragedy, one must to some extent free oneself from—betray—the very feeling of tragedy and regard it from an outer, e.g., aesthetic, point of view. Here is, by the way, an opportunity for the wildest round-dancing through ever higher ironic levels into a most embarrassing circulus vitiosus. Here one can chase one's ego across numerous habitats, enjoying the capacity of the various layers of consciousness to dispel one another. The present essay is a typical attempt at sublimation. The author does not suffer; he is filling pages and is going to be published in a journal."

Ernest Becker wrote, “Both the artist and the neurotic bite off more than they can chew, but the artist spews it back out again and chews it over in an objectified way, as an external, active work project. The neurotic can’t marshal this creative response embodied in a specific work, and so he chokes on his introversions.”

In essence, we’re all neurotic to some degree. It’s part and parcel of the dilemma of existing. The creative life offers something that no other form of terror management can: a literal outlet for existential terror.

Becker goes on to say, "The only way to work on perfection is in the form of an objective work that is fully under your control and is perfectible in some real ways. Either you eat up yourself and others around you, trying for perfection; or you objectify that imperfection in a work, on which you then unleash your creative powers. In this sense, some kind of objective creativity is the only answer man has to the problem of life.

The creative person becomes, in art, literature, and religion the mediator of natural terror and the indicator of a new way to triumph over it. He reveals the darkness and the dread of the human condition and fabricates a new symbolic transcendence over it. This has been the function of the creative deviant from the shamans through Shakespeare.

Otto Rank asked why the artist so often avoids clinical neurosis when he is so much a candidate for it because of his vivid imagination, his openness to the finest and broadest aspects of experience, his isolation from the cultural world-view that satisfies everyone else. The answer is that he takes in the world, but instead of being oppressed by it he reworks it in his own personality and recreates it in the work of art. The neurotic is precisely the one who cannot create.” Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death, 1973

TRIBALISM AND “OTHERING”

And secondly, the way we form tribes and go after the “other” whoever that may be to you. This is what my project (In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of Othering and the Origins of Evil) is about. I’m explaining the reasons for genocide, ethnocide, racism, xenophobia, hate, etc. through these theories. I’ve found that people often talk about these events but never give any solid reasons for why they happen. That’s one of my objectives in this work. I’ve also written quite an extensive section about my own journey. Starting with my own death awareness around the age of eight. I share life stories of death, othering, and the negative effects of in-groups and out-groups. In all of that, I revisited my interest in photography. How I started, what I’ve been interested in, and how this work is really the culmination of 35 plus years of thinking, wondering, and pursuing these ideas.

I recently read a great article on Alternet.org by Bobby Azarian. He is a cognitive neuroscientist and the author of the book The Romance of Reality: How the Universe Organizes Itself to Create Life, Consciousness, and Cosmic Complexity. He wrote, "Terror management theory is more relevant than ever because it provides an explanation for tribalism, which is really at the core of this mystery. The theory suggests that existential terror—which can be triggered by anything that is perceived to pose a threat to one’s existence—is the reason we adopt cultural worldviews, such as our religions, national identities, or political ideologies. In an attempt to mitigate our fears, we latch onto philosophies that give our lives meaning and direction in a chaotic world.

But how does this explain tribalism, exactly?

When we're fearful or threatened, we rally around those who share our worldviews. We become aggressive toward those who don't. More alarmingly, perceived threats or existential fears—immigrants, transgender people, gun grabbing, government conspiracies, humiliation at the hands of "liberal elites”—can stir up nationalism and sway voting habits toward presidential candidates with authoritarian personalities. For example, a study found that when primed to think about their deaths, American students who self-identified as conservatives showed increased support for drastic military interventions that could lead to mass civilian casualties overseas. Another study found that after the 9/11 terror attack, support for then-President George W. Bush spiked, ultimately resulting in his re-election."

My journey studying these theories has been life-altering. I find myself more understanding of human behavior and more tolerant and patient. I’m more open to people’s beliefs and what they lean on to quell their anxiety. As long as their beliefs aren’t hurting themselves or anyone else, I say go for it; we need to find meaning and significance in our lives to make this journey bearable.

I’m grateful and humble (or try to be) for each day I’m above ground. I’m in awe of life and the mystery of it all—my finitude and smallness are always present in my mind; I’m fully present to my cosmic insignificance. I understand that I really don’t know anything, and what I do know is very limited and only in a certain context. I have very little certainty about anything (save what I mentioned in this essay). Life is wonderful, but rarely, if ever, is it black and white. I walk in the world of the “hard place,” not the “rock place.” We are all trying our best to manage our existential terror, whether we know it or not, and most don’t.

“Three Magic Dogs in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado,” 10” x 10” (25,4 x 25,4 cm) RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print, August 15, 2023.

The Tabeguche-Ute were skilled horsemen. They were the first to get horses from the Spanish in the 17th century. They called horses “magic dogs.”

Don't Worry About Other People's Opinion of Your Work

Over the past few weeks, I’ve had a few conversations with people about making art. One topic seemed to always come up in these chats. In essence, they ask or imply, “What if people don’t like what I do or don’t understand it?” Or even, “People don’t like what I do, and they don't understand it. I don’t get very many likes or comments on social media.”

Addressing the issue of people not liking or responding to your work (social media “likes” and “comments") can be a big deterrent. And it can be a bit depressing and frustrating too. But that’s only if you give it credence or value. It’s your choice, whether you do or not. I can say with some certainty that it’s a waste of time to be concerned with what other people think about your creative endeavors, whether on social media or not; their feedback, for the most part, is meaningless. There’s an old quote attributed to a lot of different people that says, "When you’re 20, You care what everyone thinks. When you’re 40, You stop caring what everyone thinks. When you’re 60, You realize no one was ever thinking about you in the first place." I’ll be 60 years old soon and can relate to the wisdom here. Apply it to your creative life. It will make you a better artist.

This is looking west-southwest from our house. We were walking back from the top of our property and saw this. The “circle” of clouds and the ray of light on Saddleback Mountain (the far peak) were magnificient.

My response to this dilemma has always been the same: Make your work for an audience of one: YOU. That’s all that matters. This only applies if you’re making personal, fine art work. Commercial work is a different story. With that, you are bound to please a much larger audience, and it’s in pursuit of money (that’s its purpose). It’s very easy for me to separate the two. Personal work has a strong, compelling narrative. Commercial work pays no mind to that. It’s pretty and popular. It’s a transaction for money, not an expression of an idea, concern, question, interest, etc. What the masses want is something familiar and safe. Something that takes no chances and is rarely ever different. It’s what sells. Money is the object, not expression. Period. Remember the difference; that’s an important piece of understanding what you’re trying to do.

“When you’re 20, You care what everyone thinks, When you’re 40, You stop caring what everyone thinks, When you’re 60, You realize no one was ever thinking about you in the first place.”

That brings me to my second point. If you make creative work with the intention of selling it, you’re probably off to a dubious start. Influence is incessant. Making money can really mess with accessing your own creative desires. You can see how easily you’d cross that line into commercial work. And once you cross over, you’re not making work for yourself; you’re making work for them. It kills your creative vibe (in a personal sense).

I’ve said it a million times: I have nothing against commercial work. Good on you if you do it and it fills your bank account. My concerns are about not conflating commercial work with personal expression, narrative, or personal fine art. I couldn’t care less for commercial work. I have absolutely no interest in it. I’m not in the least bit concerned about selling, showing, winning awards, or anything else with my work. I make it for personal reasons, reasons that I’ve explained many times in these essays.

Carry on doing work that motivates you. If others like it or can appreciate it, great! But never make that a priority. And I would recommend that you separate making money from your creative life. Keep your creative spirit free from the poison of commerce. It destroys your soul in that context. Earn your money some other way; keep your artmaking separate and special. Enjoy every day that you can create something, or even try to create something. Reveal the failures, learn from them, and be grateful. You will be amazed at where you find yourself mentally and creatively.

In the next few weeks, I’ll share what I’ve been working on in the studio. I guess you could call it an evolution of this work. I’m super excited about it. Stay tuned!!

“Dead Foxtail and My History on My Arm,” 10” x 10” (25,4 x 25,4 cm) RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print August 12, 2023

This was an exciting image for me to make. Jeanne helped me do it (she did a great job). I wasn’t going to do any “human” photographs for this project. However, I’ve lived these stories and felt that a self-portrait might be a powerful addition to the work, I’m over-the-moon about this print. You’ll see a version of it in the book, for sure.

The Human Flight from Death: The Driving Force of Civilization

In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of Othering and the Origins of Evil}

The people who follow my writing here know that the concept of my project and book is based on Ernest Becker’s theories of death anxiety and the denial of death. Additionally, Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg, and Tom Pyszczynski—the creators of terror management theory (TMT) and authors of "The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life"—have had a significant influence on it.

My objective is to describe or explain these theories in relation to the genocide, removal, and general marginalization of the Tabeguache-Ute (known today as Uncompahgre-Ute) indigenous people. I live on their land in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, U.S.A.

I'm using art to accompany the theories. And I'm also exploring my own dilemma of coming to terms with death. This work is multifaceted, but the main objective is to communicate WHY these kinds of things happen in the world, past and present. Moreover, there are reasons why they will never stop happening.

Death: It’s a difficult topic to talk about, and we’ve evolved to repress and deny it. We've had to psychologically repress this knowledge; if we weren't able to, we would be paralyzed with anxiety and dread. We use culture to do this. All kinds of pursuits help us distract ourselves from thinking about our impeding death, which could happen at any time for any reason, unknown to us. This has a lot more implications than we realize. I recently read an article by John Gray on Substack.com. He is clear, concise, and hits all of the points of both Becker and The Worm at the Core psychologists, Solomon et al.

He wrote:

“An idea of an afterlife emerged along with human beings.

Around 115,000 years ago, graves were being fashioned containing animal bones, flowers, medicinal herbs, and valuables such as ibex horns. By 35,000–40,000 years ago, complete survival kits—food, clothing, and tools—were being placed in graves throughout the world. Humankind is the death-defined animal.

As humans became more self-aware, the denial of death became more insistent. For the American cultural anthropologist and psychoanalytical theorist Ernest Becker (1924–74), the human flight from death has been the driving force of civilization. Fear of death is also the source of the ego, which humans build in order to shield themselves from helpless awareness of their passage through time to extinction.

More than most, Becker’s life was formed by encounters with death. At the age of eighteen, he joined the army and served in an infantry battalion that liberated a Nazi extermination camp.

When he was dying of cancer in hospital in December 1973, he told a visitor, the philosopher Sam Keen: ‘You are catching me in extremis. This is a test of everything I’ve written about death. And I’ve got a chance to show how one dies.’

Becker’s theories were set out in The Denial of Death (1973), for which he received a posthumous Pulitzer Prize in 1974, and developed further in Escape from Evil, which appeared two years after his death.” (John Gray)

“Granite & Quartz Rock, Dead Foxtail, and Purple Thistles,” 10” x 10” (25,4 x 25,4 cm) Reversal Direct Color Print August 12, 2023

“Wheat, Granite Rock, and Berries,” 10” x 10” (25,4 x 25,4cm) RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print, August 7, 2023.

Change is the Only Constant: Evolution of a Project

The ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus observed that the natural world was in a constant state of movement. People age, develop habits, and change environments. You can't step into the same river twice; even rocks are subject to changes by the elements over time. Change is the only constant. It’s the same way when making art. A large project will evolve over time. If you’ve followed mine, you know that’s true.

I started this project (In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of Othering and the Origins of Evil) in September of 2021. It’s fast approaching two years now. That’s not very long for me to work on something photographically or on any kind of creative project. The time isn’t relative to me. I couldn’t care less if it took me one year or ten years to complete a project or bring my ideas to some kind of meaningful creation. My point is that this project is ever-evolving, as it should be, and may have one more huge evolutionary step taking place over the next few months.

Lately, I’ve found myself wanting to push the work in this project farther. The words “tactile” and “tangible” come to mind often as I look at the work. I’ve loved the craft of photography for decades. It’s given me so much, and it’s always been a great outlet and very therapeutic for me. However, over the past ten years or so, I’ve wanted to push my art-making farther. And this project has revealed that this is the perfect time to do that.

“It is better to fail in originality, than to succeed in imitation.”

So how do you make photography tactile or tangible? That’s the question I’ve been thinking about a lot. I see art-making as a series of problems to solve. It’s a lot like life itself. We’re faced with a series of problems to resolve every day. My tactile problem centers around two ideas. The first is to represent (abstractly) the landscape here. Specifically, the great mountain Tava-Kaavi. This is a big challenge. The second is to represent the colors. In essence, it’s the textures and colors of the land that I’m addressing. I don’t want the photographs to be taken out of context. These are the problems that I’ll be trying to resolve over the next month or so.

I’ve been reading Otto Rank’s book, “Art and Artist.” How the artist uses material to transfer their anxiety into and onto it is a powerful idea, but it does have some downsides (such as rejecting cultural constructs and being ostracized).

Ernest Becker’s interpretation of Rank’s writing in his book “The Denial of Death” has greatly influenced me as well. I really connect with Becker’s conclusion about his theories—the best answer that he could give. He said, “The most that any one of us can seem to do is to fashion something—an object or ourselves—and drop it into the confusion, make an offering of it, so to speak, to the life force.” I’ve been thinking deeply about that idea. It’s affected the way I want to approach this work.

I have to be honest and say that “straight” photography is a little bit repetitious for me. Don’t misunderstand me; I love photography, and I’m over the moon about the work I've been able to make for this project. I just feel that these ideas need more than straight photography to be represented in a meaningful and powerful way. I’ve been working on ideas to try to make that happen.

“Just as conscious contents can vanish into the unconscious, other contents can also arise from it. Besides a majority of mere recollections, really new thoughts and creative ideas can appear which have never been conscious before.

They grow up from the dark depths like a lotus, and they form an important part of the subliminal psyche.

Forgetting is a normal process in which certain conscious contents lose their specific energy through a deflection of attention.When interest turns elsewhere, it leaves former contents in the shadow, just as a searchlight illuminates a new area by leaving another to disappear in the darkness.

This is unavoidable, for consciousness can keep only a few images in full clarity at one time, and even this clarity fluctuates, as I have mentioned. "Forgetting" may be defined as temporarily subliminal contents remaining outside the range of vision against one's will.

But the forgotten contents have not ceased to exist. Although they cannot be reproduced, they are present in a subliminal state, from which they can rise up spontaneously at any time, often after many years of apparently total oblivion, or they can be fetched back by hypnosis.

Besides normal forgetting, there are the cases described by Freud of disagreeable memories which one is only too ready to lose. As Nietzsche has remarked, when pride is insistent enough, memory prefers to give way. Thus, among the lost memories we encounter, not a few owe their subliminal state (and their incapacity to be reproduced at will) to their disagreeable and incompatible nature. These are the repressed contents.”

Carl Jung

“Five-Star Flower and Berries,” 10” x 10” (25,4 x 25,4cm) RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print, August 7, 2023.

I only get this light in my studio between 0800 and 0830 in the morning (this time of year). I was so pleased when I saw this come up in the darkroom. It’s emotional to me; I can feel the geometry in the flower and the light. The small circle of light (reflected onto the background) feels like an alien looking on.

“Deer Antlers in Ute Pot: Print #1,” 10” x 10” (25,4 x 25,4 cm) RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print August 5, 2023

I’ve always found the shape of antlers interesting. The function of them fascinates me too. Mule deer are all around me in this area. I see them every day. All of the bucks are in "velvet" now. Velvet antler is defined as a growing antler that contains abundant blood and nerve supply and has fully intact skin with a covering of soft, fine hair. As the antlers develop, they're covered by a nourishing coat of blood vessels, skin, and short hair known as velvet—this supplies nutrients and minerals to the growing bone. When antlers reach their full size in late August or September, the velvet is no longer needed.

Shaping Objects With Light and Making Ideas Real

Art gives us the ability to create ideas and physically manifest them. Think about that: the ability to make something that exists only as a thought or an idea. That is mind-twisting! In my opinion, it’s a good definition of the word magic. See Becker’s quote below.

“Man has “a mind that soars out to speculate about atoms and infinity, who can place himself imaginatively at a point in space and contemplate bemusedly his own planet. This immense expansion, this dexterity, this ethereality, this self-consciousness gives to man literally the status of a small god in nature... Yet, at the same time... man is a worm and food for worms.”

It can be any form of expression—writing, sculpting, painting, music, photography, etc. Something that engages one or several of our senses. When I was young—10 or 12 years old—I wanted to be a figure sculptor. I got very interested in wax as a material. I visited a wax museum in Orlando, Florida, and I believe it was converted to Madame Tussauds a few years ago.

I was hooked. It was something about seeing the human figure re-created in such a way that you could really study it—almost feel its presence. There were Star Trek figures there; that’s what got me. I had my Polaroid portrait made with Spock. I still have that picture. It moved me tremendously.

One of my favorite things to do is use light to shape objects and bring out the essence of what they are or could be. So many people simply expose a picture and hope for the best. I think that takes so much of the creativity away. It turns creating something into a mechanical exercise.

“Deer Antlers in Ute Pot: Print #2,” 10” x 10” (25,4 x 25,4 cm) RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print August 5, 2023

"The tragedy of a species becoming unfit for life by over-evolving one ability is not confined to humankind. Thus, it is thought, for instance, that certain deer in paleontological times succumbed as they acquired overly-heavy horns. The mutations must be considered blind; they work and are thrown forth without any contact of interest with their environment. In depressive states, the mind may be seen in the image of such an antler, in all its fantastic splendor, pinning its bearer to the ground."

Peter Zapffe, The Last Messiah

The species of deer that Zapffe has in mind is the Irish elk (Megaloceros giganteus), which thrived throughout Eurasia during the ecological epoch known as the Pleistocene (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago). The Irish elk had the largest antlers of any known deer, with a maximum span of 3.65 meters. Historically, the explanation given for the extinction of the Irish elk was that its antlers grew too large: the animals could no longer hold up their heads or feed properly; their antlers, according to this explanation, would also get entangled in trees, such as when trying to flee human hunters through forests.

A surplus of consciousness and intellect is the default state of affairs for the human species, although unlike the case of the deer that Zapffe alludes to, we have been able to save ourselves from going extinct. Zapffe posits that humans have come to cope and survive by repressing this surplus of consciousness. Without restricting our consciousness, Zapffe believed the human being would fall into “a state of relentless panic” or a ‘feeling of cosmic panic’, as he puts it. This follows a person’s realization that “[h]e is the universe’s helpless captive”; it comes from truly understanding the human predicament. In the 1990 documentary To Be a Human Being, he stated:

"Man is a tragic animal. Not because of his smallness, but because he is too well endowed. Man has longings and spiritual demands that reality cannot fulfill. We have expectations of a just and moral world. Man requires meaning in a meaningless world."

The Irish elk (Megaloceros giganteus), which thrived throughout Eurasia during the ecological epoch known as the Pleistocene (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago). The Irish elk had the largest antlers of any known deer, with a maximum span of 3.65 meters.

"Cat's Eye" 10" x 10" (25,4 x 25,4 cm) RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print, July 31, 2023

Cat's Eye

The plant could be used to relieve swelling, stimulate fatigued limbs, and help with itching.

10" x 10" Color Prints Matted

I finally received 50 conservation mat boards and clear bags for my color prints. They are 12” x 12” (30 x 30 cm) with a 9.5” x 9.5” opening (24 x 24 cm). I’m very happy with them. That will give me 100 matted prints (the final edited prints) with the POP prints. These will all be published in my book.

Rick Rubin on Creativity and Making Great Art