She does a decent job of explaining these theories. Her father’s death awakened her to these ideas. It’s a five-minute video clip worth watching if you’re interested in a synopsis of Ernest Becker and Sheldon Solomon, et al.

"Pigweed,” a photogenic drawing (Henry Fox Talbot, 1830s). This is an explosion of pigweed seeds. It’s how the plant reproduces. It’s a wild edible. Native Americans made tea from the leaves (used as an astringent). It’s also used in the treatment of profuse menstruation, intestinal bleeding, diarrhea, etc. An infusion has been used to treat hoarseness (voice) as well.

We're Animals, With One Caveat

I’ve never considered or really pondered the fact that I’m an animal. You’re an animal, too. What does this mean, or why does it matter?

It plays a significant role in the theory that I’ve been working on and studying for this project. It demonstrates the need for humans to isolate themselves (psychologically) from other animals. It’s a critical part of believing in our illusions—illusions to alleviate our death anxiety.

It doesn’t surprise me, though. As I peel this onion of human behavior, each layer reveals something new. I see where all of this fits and why it is the way it is—we need it this way to get out of bed in the morning,

These are cultural constructs to convince ourselves that we're "more" or "above" the animals. But we’re not. The evidence is in the way we hide our bodily functions and how we eat; hiding our animality is very apparent in things like "bathrooms," "plates, cups, forks, spoons, and tables," as well as "making toasts with drinks." Think about it. Observe other animals; how do they handle these functions and tasks?

These are all cultural constructs to help us disguise or hide our animal nature—you’ll never see other animals doing these things. We even disguise our food with names like "steak" or "hot dog." Those words have no real meaning as they apply to food. They are simply used to disguise what we’re doing.

We even disguise sex, the most animalistic behavior of all. We wrap it in "love" and make it something special, rather than simply acknowledging that it's an act of reproduction—an evolutionary drive just like survival. And we do it just like the rest of the animals. This is one of the reasons there are so many taboos, rituals, and rules around sex in different cultures. Ernest Becker said, “The distinctive human problem from time immemorial has been the need to spiritualize human life, to lift it onto a special immortal plane, beyond the cycles of life and death that characterize all other organisms. This is one of the reasons that sexuality has from the beginning been under taboos; it had to be lifted from the plane of physical fertilization to a spiritual one.”

Because of its animalistic nature, it’s an act that most reminds us of our mortality. That’s why we create all of the celebrations around it: flowers, chocolate hearts, “love letters,” fancy dinners, lingerie, holidays, etc. We want to elevate it as an act of “love” way beyond what the “animals” do; we make it “special” because we’re “special.”

It’s a difficult topic to unpack in the context of death anxiety. However, at its core, it reveals our animal nature and what we’ll devise in order to never face it or even admit what it really is.

“Yet, at the same time, as the Eastern sages also knew, man is a worm and food for worms. This is the paradox: he is out of nature and hopelessly in it; he is dual, up in the stars and yet housed in a heart-pumping, breath-gasping body that once belonged to a fish and still carries the gill-marks to prove it. His body is a material fleshy casing that is alien to him in many ways—the strangest and most repugnant way being that it aches and bleeds and will decay and die. Man is literally split in two: he has an awareness of his own splendid uniqueness in that he sticks out of nature with a towering majesty, and yet he goes back into the ground a few feet in order to blindly and dumbly rot and disappear forever. It is a terrifying dilemma to be in and to have to live with. The lower animals are, of course, spared this painful contradiction, as they lack a symbolic identity and the self-consciousness that goes with it. They merely act and move reflexively as they are driven by their instincts. If they pause at all, it is only a physical pause; inside they are anonymous, and even their faces have no name. They live in a world without time, pulsating, as it were, in a state of dumb being. This is what has made it so simple to shoot down whole herds of buffalo or elephants. The animals don't know that death is happening and continue grazing placidly while others drop alongside them. The knowledge of death is reflective and conceptual, and animals are spared it. They live and they disappear with the same thoughtlessness: a few minutes of fear, a few seconds of anguish, and it is over. But to live a whole lifetime with the fate of death haunting one's dreams and even the most sun-filled days—that's something else.” Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death

If we accept that we are animals, we are reminded that we will die and become “food for worms,” as Becker said—just like all of the other animals.

If you’ve seen the movie "Elephant Man," the line spoken by John Merrick really solidifies this idea. He said, "I am not an animal! I am a human being. I am a man." I know he was saying this in reference to his birth defect and appearance (the way he was being treated), but the argument still stands about how we feel about denying our animality and how insistent we are to separate ourselves from all other living things.

There can be a religious component to this belief. I understand why that is as well. In order to have the illusion of (literal) immortality, which we desire, there has to be something that sets us apart. Some religions even go as far as telling man to "take dominion over all living things and all of earth" (paraphrased). It’s easy to see how humans can believe that they are above other life. There’s another component to this: "Man was created in the image of God." This escalates into an even bigger problem. If you ask most religious people if they believe they’re an animal, they will say, "No, I’m special, created in the image of God; how could I be an animal?" This is what I was referring to in my post about Becker’s hero system. This is the religious component of that theory. It’s an effective illusion if one can maintain it. Both Friedrich Nietzsche and Ernest Becker believed that religion was no longer a valid hero system because of advances in science and technology, and because of these advances, most people have “moved on.” That’s where Nietzsche’s infamous quote came from: "God is dead." This was the idea behind it. Religion acted as a buffer against death anxiety for most people for thousands of years, all over the world, in all kinds of religions. In the last 200 years, we’ve become much more secular and tend to look to culture for our defense against death anxiety. Here again, you can see where we have denied our animality with these religious tenets—placing ourselves above every living thing and the earth itself.

What’s the caveat? What makes us different from animals? We have consciousness, or awareness, of our mortality. Your dog or cat doesn’t know that they’re going to die. They’re completely in the moment of “now.” There are no rabbits talking about being the best rabbit alive! Animals exist with instincts to survive and reproduce. At times, they may have the fight-or-flight instinct and be very afraid, but once out of danger, they never think about it again. In our unconscious mind, we are constantly in fight-or-flight mode. William James said, “There is always a panic rumbling beneath the surface of consciousness.” That panic comes from the knowledge of our impending death. Other animals don’t have this; that’s really the only thing that makes us different. It fascinates me to look at how we live and act, denying the inevitable (our death) and trying to hide the fact that we are animals. We would show our animality if we didn't have this knowledge. We would be exactly the same as all of the other animals.

I’m slowly, but surely, putting these pieces together. These are the pieces of these theories that show us who we are and why we are the way we are: human behavior. I’m specifically interested in the reasons we commit evil acts and how our death anxiety is revealed through acts of genocide, racism, bigotry, xenophobia, and “othering.” We have so much to learn about these topics. In the end, I hope to share a tiny piece about the role that art can play in disclosing ways to deal with these big topics.

“Denial of death, or, in psychodynamic terms, repression of death anxiety, generally results in banal and/or malignant outcomes—for example, preoccupation with shopping or the need to eradicate people who do not share our beliefs in a self-righteous quest to rid the world of evil. Repressed death anxiety is often projected onto other groups who are declared to be the all-encompassing repositories of evil and who must be destroyed so that life on earth will become what it is purported to be in heaven.”

Sheldon Solomon author of “The Worm at the Core: The Role of Death in Life

A whole-plate palladiotype print from a dry collodion negative made at 9,000 feet (2,800 meters) above sea level, I call this “Stone Water Dish,” balancing in nature almost like a symbolic reference to life. To Indigenous peoples, all of earth's elements are valuable and important. However, rocks are considered to be the wisest of all Earth's elements! After all, rocks have been around the longest, for millions, if not billions, of years. Because rocks are so old and have many stories to tell, Indigenous peoples sometimes call the Earth's rocks “grandfathers.”

Are You Doing Too Much or Not Enough?

I recently had a conversation with someone about the ubiquity and nature of photography. We talked about how a creative person working in photography can approach making meaningful and significant work and what effect all of these changes since its invention have had on the medium.

We discussed how technology has changed photography and the impact "commonness" has had on the craft—some call this the "democratization" of photography, which I think is a fair statement, but it's had a significant impact both times it's happened. It has altered how we perceive photographs (and their worth) and how creative people work with the medium. The first wave came in 1900 with the Kodak Brownie ("You Press the Button, We Do the Rest"), and the second came in the early 2000s with the advent of consumer-model digital cameras and iPhones (2007).

The conversation went on about different approaches to making art and why some are more effective than others. And we briefly touched on the AI (artificial intelligence) models creating "wet collodion" images from text prompts; there's not much to say about this topic in my opinion.

I’ll give you a brief overview of how the conversation unfolded.

There’s a balance to making art, specifically in photography. Using photography today can lead a person down a path of "thumb-twiddling," especially now with digital image making, which is instant and easy. It can happen with film or historic processes as well. The latter happens in a different way, but it has the same result: vagueness and meaninglessness.

What I mean is that you can meander aimlessly (and easily) into never making anything with substance or weight. You photograph anything and everything with no intention other than the hope that it appeals to someone, somewhere, or you copy what you’ve seen. You have nothing to say about it and nothing to connect it to (no purpose or a very vague purpose). It’s just there, on its own, with no defense and nothing to offer but what the viewer brings to it. It’s mechanical in the truest sense of the word. This is what Baudelaire warned us about so long ago. He was right; he’s always been right.

You can also fool yourself into thinking that you’re making deep, meaningful work when you’re not. The “art talk” in statements leaves the reader confused with what the vague or derivative work is intended to evoke—no one knows, not even the writer of the statement or maker of the images. The intention is to fool the viewer. The statement might read something like this: “Ever since I was a pre-adolescent, I have been fascinated by the endless, ephemeral oscillations of the mind. What starts out as contemplation soon becomes corrupted into a hegemony of defeat, leaving only a sense of unreality and the chance of a new understanding.” What?? This is why the layperson is turned off when it comes to art, artists, and galleries. If they could see how shallow and fake this stuff is, they might reconsider. No one ever talks about the emporor having no clothes; everyone seems to play along.

In essence, you hope the viewer will see something you didn't or understand something you don’t. You hope, through their life filters, they see "something" and make a connection with it. In reality, you’ve created nothing. You’ve expressed nothing. You’re not in control. You’re a machine that’s regurgitating photographs that you’ve seen before. Trying to gain self-esteem by riding the coattails of something that’s been done a thousand times—I know that plenty of people can write dissertations on the validity of this approach to making photographs; I’ve read a lot of them, but they've never justified the blind ambition and aimlessness of working in such a superficial, meaningless way. Never.

When people do this with historic processes or film photography, they concentrate on processes, techniques (process photography), and gear. It’s always about the process, technique, or gear—never about the content of the photograph or what it’s authentically connected to. In some cases, they may try to argue that it's related to something, but it's always vague (see statement above), and the process or gear takes precedence. We have social media to blame for a lot of this. The high "wow-factor" is what gets people to look and "like." And people are always up for learning something for free and then emulating or copying it if it’s popular enough. If they can commodify it, even better.

It seems we are constantly seeking outside validation for our work. We’re always trying to bolster our self-esteem. We want accolades, awards, "wins," and acknowledgement of our creative and technical skills. And we want other people to know what we’ve achieved. In essence, we want to rise above and be the "one in creation," as Becker said. We rarely, if ever, consider our own validation about what we’re doing and why. The existential anxiety would be minimized if we could understand the value of our work without seeking external validation—without hovering around narcissism and navel-gazing. I think this comes from gratitude: truly appreciating what you've made, the reasons you've made it, and the ability to understand its place in the world. Facing the reality of your life and why you do what you do—if we could stop the denying and self-deception, we could see a clear path to why we are the way we are.

That’s where we’re at. When I ask the question, "Are you doing too much or not enough?" The answer is "yes." If you’re doing this, you’re doing both too much and not enough. Too much influence from outside of you (social media, trends, etc.) and not enough self-examination and contemplation—authentically exploring what you’re passionate about and want to share—and forget the standards of success (social media popularity, money, articles, interviews); they are meaningless if you’re not really connected to the work.

The conversation ended with me conceding everything I was ranting about. In the end, it’s all meaningless, so I suppose one could make the argument that doing whatever distracts from reality or buffers the anxiety should be valid. It’s a coping mechanism. And if you pressed me, I would agree. Since none of it matters, it’s all valid, at least in the big picture (no pun intended). My point is that if you’re finding your buffer through "thumb-twiddling" digital work or photography gear and processes and you’re not hurting anyone, go for it! That’s how I ended the conversation. They understood what I meant.

After having this dialogue, I realized that it connected so beautifully to the work on death anxiety that I’ve been doing. It’s literally a metaphor for our lives. It describes how we need to create meaning and significance in order to live from day to day or even get up in the morning. Without meaning and significance or building self-esteem, we wither—we get depressed, we lose hope, and we fall into despair. This creation of meaning, in whatever form, is vital to our well-being.

And, unconsciously, we all know that what we do is meaningless—everything we do—but we just can’t face it. I know it sounds harsh and negative, but it’s the truth. This is what the Norwegian philosopher Peter Wessel Zapffe made clear about consciousness: the knowledge of our death and the impermanence and insignificance of life is a terrible burden to bear. Making art is used in what he calls "sublimation." It’s used as a distraction, or more accurately, as a transference object. Our existential anxiety is projected (transferred) onto the art. It makes so much sense to me. While I’m no different than anyone else, I do understand my predicament, or my paradoxical condition, if you will. Art allows me to intellectualize my impending death. In a lot of ways, it allows me to come to terms with it. Everything you just read here is sublimation, and everything I create is sublimation. I’m resolved to face that, and I think we would all be better off if everyone could do the same.

"If someone can prove me wrong and show me my mistake in any thought or action, I shall gladly change. I seek the truth, which never harmed anyone; the harm is to persist in one's own self-deception and ignorance." ~ Marcus Aurelius

“The Great Mullein” (Flowering)-Whole Plate Kallitype from a Wet Collodion Negative - Aug. 6, 2022

Native Americans utilized it for ceremonial and other purposes, as an aid in teething, rheumatism, cuts, and pain. It's also used for a variety of traditional herbal and medicinal purposes for coughs and other respiratory ailments. Verbascum thapsus

What Kind of Hero are You?

Henry David Thoreau said, “If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away.“

I suppose it’s my quiet life that allows me to reflect, observe, and, most importantly, think about human behavior, including my own. It seems to be constantly on my mind. To say I’m preoccupied with it would be an understatement. I’m very cognizant that this is a privilege most people don’t have.

Every day, as I write my book, I find myself wondering why so few people ever stop and reflect on their lives or try to understand their nature. Everyone seems to be so wrapped up in schedules, shopping, money, status, appearance, and all other kinds of distractions or busy, frantic material lives that keep them ensconced in their illusion that they have no time for thinking about these things. I understand why they need this. I get it. However, that wouldn’t prevent self-examination or reflection.

The theme of my book is to make the unconscious conscious so that it doesn’t direct your life. I feel like this is missing in so many people’s lives. It reminds me of the diet/food question. If people were aware of what they ate, they wouldn’t wonder why they felt so bad and were always sick, tired or depressed. They’re in the same psychological area. We have such a strong drive to “enjoy the moment" that we rarely look past that or the consequences we pay for doing it.

Ernest Becker asked, "…the question of human life is this: On what level of illusion does one live? This question poses an absolutely new question for the science of mental health, namely, what is the “best” illusion under which to live? Or, what is the most legitimate foolishness? ... I think the whole question would be answered in terms of how much freedom, dignity, and hope a given illusion provides.” (The Denial of Death)

The question is: what illusion or illusions are you using to quell death anxiety? Have you ever thought about this? Are your illusions hurting or damaging other people or yourself? Becker was concerned about adopting harmful illusions to buffer death anxiety. History is littered with people who have used illusions to cause millions to suffer and die (most extreme cases).

Becker talks about four types of heroism—ways we can use culture to bolster our self-esteem, which keeps existential terror at bay. These are the illusions we use to function day-to-day.

RELIGIOUS HEROISM

The first is religious heroism. This is still used today, but not like it was in the past. Before the enlightenment and the industrial revolution, among other advances, this was the way most people buffered their anxiety. A promise of an afterlife (immortality) and meaning and purpose from a higher authority is what worked. Most religions have convinced believers “that one's very creatureliness has some meaning to a Creator; that despite one's true insignificance, weakness, death, one's existence has meaning in some ultimate sense because it exists within an eternal and infinite scheme of things brought about and maintained to some kind of design by some creative force." (The Denial of Death) This type of heroism is no longer viable for most people.

CULTURAL HEROISM

The second is cultural heroism. This is what eclipsed religious heroism. Most people today lean toward this type of heroism. The average person can’t become a famous musician, movie star, or sports legend. It’s not realistic. So they become "cogs" in a heroic machine. It could be their society, their country, or a corporation. Something "bigger" than themselves that will live on beyond their physical death. "Man earns his feeling of worth by following the lines of authority and power internalized in his particular family, social group, and nation," Becker explained. "Each human slave nods to the next, and each earns his feeling of worth by doing the unquestionable good." (The Ernest Becker Reader) Becker really makes a profound observation when he says, “Take the average man who has to stage in his own way the life drama of his own worth and significance. As a youth he, like everyone else, feels that deep down he has a special talent, an indefinable but real something to contribute to the richness and success of life in the universe. But, like almost everyone else, he doesn’t seem to hit on the unfolding of this special something; his life takes on the character of a series of accidents and encounters that carry him along, willy-nilly, into new experiences and responsibilities. Career, marriage, family, approaching old age—all these happen to him, he doesn’t command them. Instead of his staging the drama of his own significance, he himself is staged, programmed by the standard scenario laid down by his society.” (Ernest Becker, Angel in Armor: A Post-Freudian Perspective on the Nature of Man) This is so easy to see; it may have even happened to you. Having life “happen” to you rather than you actually controlling it, I can relate to this statement, and it applies to my early life for sure. Cultural heroism transforms individuals into blind conformists.

PERSONAL HEROISM

The third is personal heroism. Becker described this type of individual as "one who tries to be a god unto himself, the master of his fate, a self-created man. He will not be merely the pawn of others, of society; he will not be a passive sufferer and secret dreamer, nursing his own inner flame in oblivion." (The Denial of Death) This type of person tries to find their authentic talent and uses it as a way to measure their worth. “If I were asked for the single most striking insight into human nature and human condition, it would be this: that no person is strong enough to support the meaning of his life unaided by something outside him,” (Angel in Armor) According to Becker, this is doomed to fail.

THE GENUINE HERO

And finally, Becker talks about the genuine hero. This is a rare individual who does not require illusions to live, a person who can face the reality of their existence head-on, no holds barred. "I think that taking life seriously means something such as this: that whatever man does on this planet has to be done in the lived truth of the terror of creation, of the grotesque, of the rumble of panic underneath everything. Otherwise, it is false." (The Denial of Death) The genuine hero lives with an attitude of resignation that is not a pessimistic denial of life. They recognize the awesome powers of the universe and that those powers dwarf their petty concerns. He concluded his train of thought with this, ''The most that any of us can seem to do is to fashion something - an object, or ourselves - and drop it into the confusion, make an offering of it, so to speak, to the life force.” (The Denial of Death)

“Ode to Vincent van Gogh” (self-portrait) from the show “Visions in Mortality.”

Manipulated Polaroid direct positive, copyright © Quinn Jacobson 1993

Visions In Mortality - 1993

I just finished writing about my first photographic exhibition in the biography portion of my book (Chapter 2, The Introduction). After careful consideration, I felt it was important to give my background on these theories and ideas in the context of what I'm doing now. It makes so much sense to me now. There is some kind of closure that I feel after all of these years making art about the fear of death and the human behaviors that result from it. I wouldn’t say that I was working blindly or aimlessly all those years; it was more like I was trying to express ideas that I had no concept of explaining with words. It was the intellectual part that was missing. That’s all changed now. I understand what I was doing, and it all fits together beautifully. I am beyond grateful for that.

Over 30 years ago, I was making work about the same things I’m making work about today. The difference is that I’m so much more mature (artistically speaking) and feel like I have a good grasp on these concepts and how to articulate what concerns me. I wrote about my exhibition called "Visions in Mortality." This body of work was exhibited for a few weeks in 1993 as my senior thesis project for undergraduate school.

The images were all manipulated Polaroid work (direct color positives) and poetry. Each image was accompanied by a short poem or passage. I was very influenced by Lucas Samaras and Charles Bukowski at the time. The overall theme was what I’ve always made work about: death anxiety and the knowledge of our mortality. However, as you can see from the statement below, I was venturing into the defense mechanisms that I'm writing about today concerning the denial of death.

In my book, I wrote about four of the 25 or so images from the show. “Clotheshorse,” “Coitus on a Sea of Blue,” “Ketchum, Idaho,” and this one, "Ode to Vincent van Gogh.” This is a self-portrait. I was 29 years old. The image came about by accident while moving the chemistry around during development—the lower portion of my ear was gone. After seeing it emerge, I immediately thought about the painting of Vincent van Gogh—the self-portrait with his bandage and cap—and the self-mutilation and suicide. And the Yellow House.

On the 23rd of December 1888, in a small house in Arles, in the south of France, one of the most famous artists of all time—Vincent van Gogh—feverishly cut off his own ear in a mysterious act of self-mutilation. The circumstances in which van Gogh cut off his ear are not exactly known, but many experts believe that it was following a furious argument with Paul Gauguin at the Yellow House. Afterwards, van Gogh allegedly packaged up the ear and gave it to a prostitute in a nearby brothel—that wasn’t true; he gave it to a cleaning lady. He was then admitted to a hospital in Arles, France. He died by suicide about 18 months later, on July 29, 1890.

Mental illness has been a long preoccupation of mine—all human behavior, really. I’ve always wondered, just like any marginalized community, why these afflictions happen. I feel like I have some answers now, and while they are not definitive or absolute, they do point me in the right direction for why these kinds of things happen to people. I address suicide in my "Ketchum, Idaho” image as well. It’s a self-portrait sitting on the grave of Ernest Hemingway. These questions have always been present in my work.

Here’s my artist’s statement from the show in 1993—this is verbatim:

“Visions in Mortality”

This project deals with the reality of life, which is death, both visually and textually. This project is meant to communicate the intense and complicated process of life and our struggle with mortality as we approach death.

Whether life is short or long, it inevitably consists of much pain, suffering, depression, hurt, confusion, boredom, and misery, with only a “sprinkle” now and then of happiness, joy, love, peace, honor, and understanding. So many people are on the futile quest to attain happiness and understanding through physical, materialistic, and intellectual means that they neglect to realize their failure and ultimately find themselves in a “mortality crisis.”

This project deals with both the long term “reality” of life and few and far between “sprinkles” of the good stuff. It represents what I and many others see, feel, and experience as the human race.

Overall, this imagery communicates that both life and death are frightening, beautiful, and mysterious conditions.

“Three Aspens” - Whole Plate Kallitype from a wet collodion negative. Here in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, aspens are known as “fire-breaks” because of their high moisture content. They will help stop the spread of a wildfire. They act as a guard against fire tornadoes and absolute destruction during a wildfire. Native Americans used aspen trees to make Sun Dance lodges, dugout canoes, and deadfall traps for bears. Poles provided tepee frames and scrapers for deer hides. Knots could be made into cups, and bark could be made into cording.

Denial: Self-Deception, False Beliefs, and the Origins of the Human Mind

I just finished reading the book "Denial: Self-Deception, False Beliefs, and the Origins of the Human Mind" by Ajit Varki and Danny Brower. It’s an amazing book that posits a profound theory about how the human mind evolved and the obstacles it overcame that allowed us to be the way we are today—intelligent, creative, and innovative. It’s all based on our denial of reality. “The potent combination of our powerful intelligence with our massive reality denial has led to a dangerous world…” (Denial page 221)

It seems that we’ve been asking the wrong questions about human evolution and the evolution of the mind. The questions put forth in the book are, "Why is there no humanlike elephant or humanlike dolphin, despite millions of years of evolutionary opportunity?" And, "Why is it that humans alone can understand the minds of others?" The theory in the book is directly related to my project—how death anxiety and the repression mechanisms we use came to be, and the functions they served in the history of human evolution.

This is not a book review; I’m just connecting the dots with my work and sharing some insights as they pertain to death anxiety and the denial of death. It gets to the core of my project about denial. It addresses why we are “wired” to deny reality and how that leads to malignant manifestations of death anxiety, which is the crux of my work and project.

It’s important for me to understand the origins of the denial of death and death anxiety. These ideas are the mainspring of my book. I’ve been trying to find answers to these questions for a while. Fortunately, I received an email from a person who shares similar interests (Thanks, Tim!). He recommended that I read the book. Sheldon Solomon mentioned the book on a podcast I was listening to, and I made a mental note to look into it but never got around to buying the book. I’m very happy that I finally did.

It’s given me a lot of fodder for my endeavor and answered a lot of questions for me. Not to mention, I learned a lot about the evolutionary origin of humans and the cognitive psychology and evolution of the human mind.

Varki makes it very clear that these are not falsifiable theories and that he speculates a lot about them. I like that he’s approached it in an honest and scientific manner. I respect that. It leaves the proverbial door open to being proven wrong and to making better “guesses” in the future. This is how science works.

Varki relates an interesting and sad story about how he met Dr. Danny Brower. It was Brower’s theory that piqued Varki’s interest. The book was born from a conversation that lasted less than two hours. How it all came about is too lengthy to go into here, but it was fascinating and sad.

One of the main topics of the book is the Theory of Mind (ToM) or as some might call it, “consciousness.” As the author points out, there are so many definitions of that word that it’s better to be more definitive. Some may call it “self-awareness,” and it is to a degree. As the author says, this is a continuum from rudimentary self-awareness to full ToM. ToM is the ability to infer and understand another's mental state—their beliefs, thoughts, intentions, and feelings—and use this information to explain and predict human behavior. The book explains why denial is a key to being human. Varki posits that we separated ourselves from the other creatures because we grasped self-awareness of ours and others’ mortality (ToM) and then just as quickly developed a way to deny that mortality. And that’s what my writing is about: the way we deal with death anxiety and what that can lead to (racism, bigotry, genocide, and crimes against humanity).

The theory posited in this book can be summed up this way: Mind Over Reality Transition (MORT) theory. MORT is the evolutionary adaptation in response to gaining theory of mind (ToM) by simultaneously evolving denial of reality. There it is: a few words that describe the essence of a 300-page book. Obviously, the details are important, but that’s the ultra-condensed version of the book.

We deny reality—that reality being our mortality (among a lot of other things). In order for us to be so intelligent, we needed to develop a full theory of mind (ToM). What comes along with ToM is the awareness of death. If the animal has no mechanism to deal with that—to deny it—they will not survive. Varki believes that other animals have repeatedly crossed the barrier over millions of years, having full ToM but not the mechanism to deny mortality. This leads to an evolutionary dead end. The only animal that has successfully crossed over is us, (behaviorally) modern homo sapiens.

So how did early (modern) humans gain a full theory of mind and a denial mechanism at the same time—something that no other animal has been able to accomplish? Varki and Brower present the idea that a denial mechanism was starting to form before full ToM arrived. It came in the form of lying. The main drive was to create offspring before MORT, so lying was a great way to get the best partner to make babies. I'm not sure how they lied; perhaps they claimed to have killed the largest lion or provided the most meat; who knows, but as a theory, it makes sense to pre-MORT. The ability to lie to others led to the ability to lie to oneself. Self-deception led to denying reality, and denying reality led to full ToM and MORT.

What a great story of evolutionary biology and evolutionary psychology! It’s really put things in perspective for me. I know there are a lot of ideas in this theory that I’ll use for my book, connecting evolutionary biology and psychology to the actions of genocide and crimes against humanity. It ties in so nicely and explains so much of human behavior. It does give a great foundation for my studies and interests.

Live Stream on January 7, 2023: In the Shadow of Sun Mountain

I hope you can join me on Saturday, January 7, 2023. I’ll be doing a live video stream via my YouTube channel and/or Stream Yard. You can watch and chat (text) on YouTube, or you can join in with video/audio on Stream Yard.

I’m going to talk about the progress on my project, “In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of Othering.” I’ll share some of the work, talk a little bit about my writing and research, and just give a general update. I’m happy to have a discussion and answer questions, too.

I’ve been working on this for just over a year (started the work in September 2021). I hope to complete it by the end of 2023 or the beginning of 2024. I’ll talk about all of that and share some interesting insights about working on a project like this. I’ve had a couple of questions about how I’m connecting the death anxiety/psychology to the photographs. It should be an interesting conversation.

Stream Yard link (for live video): https://streamyard.com/se43n54spq

YouTube link (chat): https://youtu.be/_uIYtPkYMw4

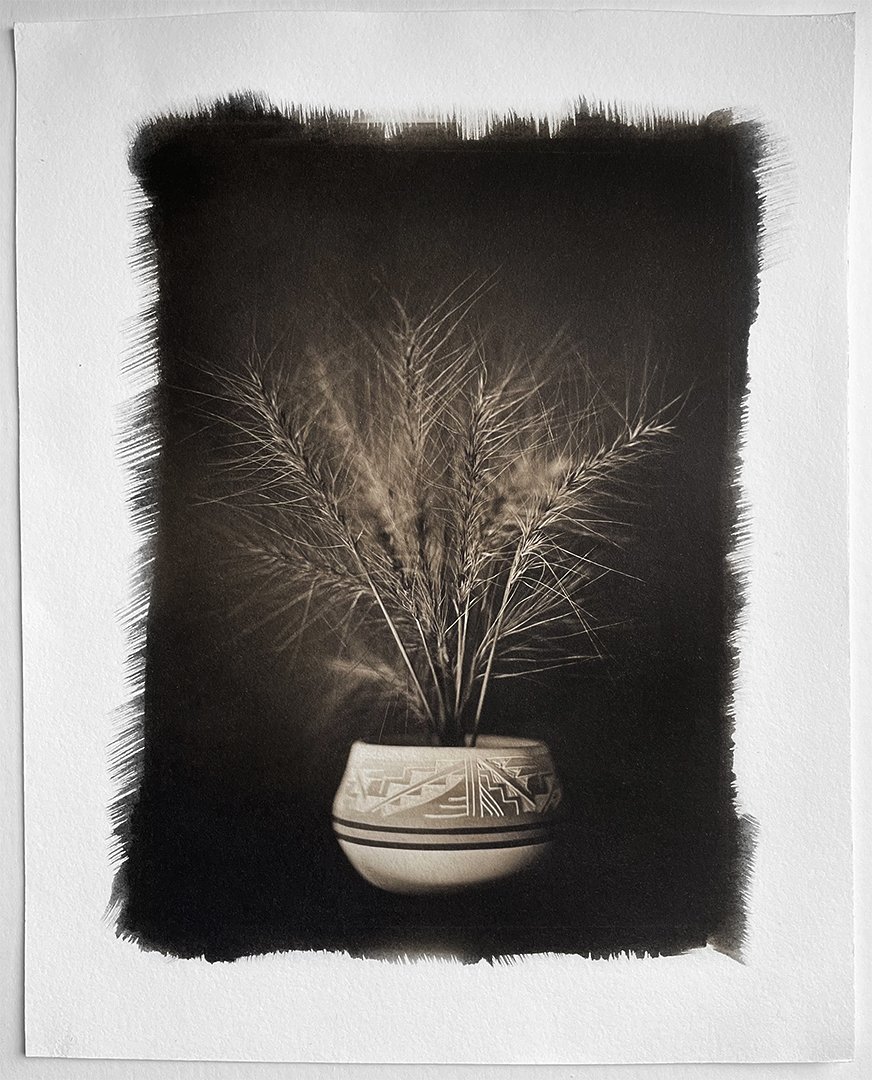

MEADOW BARLEY

The small grains are edible, and this plant was part of the Eastern Agricultural Complex of cultivated plants used in the pre-Columbian era by Native Americans.

Whole-plate palladiotype print from a wet collodion negative

I like how the brushstrokes of the palladium mimic the plant itself. I made this with an old Derogy lens wide open. For me, the falloff adds a lot of emotion and poetry.

Becker's Transference and Transcendence Theories

“The human animal is a beast that dies and if he's got money, he buys and buys and buys and I think the reason he buys everything he can buy is that in the back of his mind he has the crazy hope that one of his purchases will be life everlasting!”

― Tennessee Williams, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

Trained in cultural anthropology, Dr. Ernest Becker was motivated in his work by an overriding personal pursuit of the question, "What makes people act the way they do?" Refusing to dismiss answers to this question coming from any field of study based on empirical observation of human behavior, Becker almost inadvertently created a broadly interdisciplinary theory of human behavior that is neither simply speculative nor overly reductionist. Becker's synthesis, which is found in the title of his most famous book, "The Denial of Death," describes human behavioral psychology as the existential struggle of a self-aware species trying to deal with the knowledge of death.

Every day we are confronted with the reality of death and our own mortality. Simultaneously, we are strongly motivated by a survival instinct. Ernest Becker's existential psychological perspective came from this realization. His basic ideas have been largely substantiated in clinical testing conditions by a theory in social psychology called Terror Management Theory, created by American psychologists Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg, and Tom Pyszczynski. Their book, "The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life," provides the empirical evidence for Becker's theories.

Death is a complex struggle for human beings. The repressed (unconscious) knowledge of death keeps anxiety at bay and out of consciousness. We are born into culture, and the socialization process is largely one of learning how our culture symbolizes death. These cultural worldviews, as Becker calls them, are what we use to create the illusions we live in. The "urge to heroism," as he puts it, is what allows us to boost our self-esteem and manage our existential terror. In other words, our culture gives us opportunities, or not, to bolster our self-esteem, and in response, these illusions that our culture provides act as a buffer to our repressed knowledge of mortality.

How we symbolize death strongly impacts our sense of what the good life is and how we conceptualize the enemies (both personal and political) of ourselves and our society. Our culture's ways of heroically denying death and our habits of buffering ourselves too much or too little against the rush of death anxiety shape who we are as a society and as individuals.

As a symbolic defense against death, it's natural for people to try to ground themselves in powers bigger than themselves. It's also natural to feel attacked when our higher powers are taken away.

Freud coined the term "transference." He used it to describe a person, usually a client, transferring their feelings for another person to the therapist. In other words, the client may love their spouse, and during therapy, these feelings are "transferred" to the therapist.

Becker took this theory and applied it beyond the "client/therapist" model to almost anything. Human beings are constantly trying to mitigate their death anxiety. Using the terror management theory, they will "transfer" their love and admiration to an object in order to quell existential terror. This can be anything from a pair of tennis shoes to a religious deity.

After I read about this, I see it everywhere now. Sports teams, holidays, celebrities, cars, clothes, photography equipment—all of it seems to be used as transference objects. Because the majority of you who read these essays are photographers, I'd like to share one example from the world of photography.

Have you ever seen someone who gets a new (large format) camera and posts photographs of it? And, every now and then, a self-portrait with the camera? We’ve all done it. The bigger the camera or lens, the better. Most would apply Freud’s theory of compensation (sexual repression) to these images. In reality, Becker’s theory of transference applies here. It’s not sexual; it’s a transference object to stave off death anxiety. This can be applied, as I said before, to anything: clothes, boats, trucks, record players, computers, even spouses or significant others. Becker’s got an explanation for transference in humans; he concludes the segment with the fact that the partner worships the other person as a deity (think about the first dates) and then realizes that they have "clay feet." In other words, the transference eventually ends, and the spouse is seen as a mortal human that will eventually die.

Becker makes it very clear. We are temporarily relieved from the drag of "the animality that haunts our victory over decay and death." When we fall in love, we become immortal gods. But no relationship can bear the burden of godhood. Eventually, our gods and lovers will reveal their clay feet. It is, as someone once said, the "mortal collision between heaven and halitosis." For Becker, the reason is clear: "It is right at the heart of the paradox of man. Sex is of the body, and the body is of death. Let us linger on this for a moment because it is so central to the failure of romantic love as the solution to human problems and is so much a part of modern man’s frustrations."

Let me see if I can explain this as it relates to my work. This is another example of the way humans deal with the knowledge of their impending death and attempt to stave off the dread and fear of it. To me, it’s the most basic example of witnessing human behavior "in action" and quelling their existential dread. They don’t even know they’re doing it. It’s all unconscious behavior in service of repressing the knowledge of their mortality. These transference objects provide transcendence too. The person indulging feels "immortal" and is transcending death.

Human nature tends to lean toward the malignant manifestations of these theories. That’s what my work addresses: genocide, crimes against humanity, and "othering." Rather than using transference to tranquilize with the trivial, i.e., clothes, cars, lovers, drugs, shopping, TV, Facebook, and Twitter, some use human beings through violence and subjugation as transference objects.

Throughout history, we’ve seen human beings use "the other" to bolster their self-esteem and stave off death anxiety through torture, subjugation, and murder. That’s why, for me, it’s very important to understand these theories as they apply to the history of my work. The transference and transcendence theories are just more examples of the human condition. They answer, in part, the reasons for evil in the world.

“The Illuminated Sunflower," a whole-plate palladium print from a wet collodion negative.

I can’t ask what the “punctum” is in this image. I see it, and I can’t describe it. This is what makes photography, and the ideas behind it, interesting to me,

Roland Barthes: Studium & Punctum

A year or two ago, I had a YouTube show where I talked about Roland Barthes’ book, "Camera Lucida: Thoughts on Photography." It was published in 1980. In the book, Barthes questions the nature of photography and comes to some interesting conclusions and thoughts about it. I want to talk a little bit about what he calls "studium" and "punctum" in photography.

He thinks a lot about the relationship between photography and death. That interests me a great deal. As I work on my project (In the Shadow of Sun Mountain), I find myself connecting the photographs and death quite often. I have a lot of medicinal and ceremonial plants that I’ve photographed for my work. A lot of them made very nice images; they are beautiful and interesting to look at and think about. However, they’re all dead now; only the photograph remains. If you read Susan Sontag’s book “On Photography,” you'll find that she had some of the same (or at least similar) positions as Roland Barthes on this topic. It’s not a stretch to make these connections. Death and photography are twins. As Sontag said, “Photography is momento mori.”

The photograph captures a moment when the person photographed is neither subject nor object. He perceives himself as an object; he has "a micro-experience of death." The person in the photo no longer belongs to himself; he becomes a photo object that society is free to read, interpret, and place according to its will. This is a great way to explain what photography does: it objectifies. This makes it both interesting and dangerous, and I don’t think many “photographers” think about this, especially when photographing certain groups of people.

The target of the photograph is necessarily real. The subject existed in front of the camera, but only for a brief moment, which was recorded by the lens. The object was therefore present, but it immediately becomes different, dissimilar from itself. Barthes concludes from this that the noema (the essence) of photography is "it-has-been." The photograph captures the moment, immobilizes its subject, testifies that he "was" alive, and therefore suggests (but does not necessarily say) that he is already dead. The direct correlation to memento mori can be found here; if he isn’t dead now, he will be.

Photography brings a certainty of the existence of an object. This certainty prevents any interpretation or transformation of the object. The death given by photography is therefore "flat," because nothing can be added to it. In photography, the concrete object is transformed into an abstract object, the real object into an unreal object. The subject of a photograph is no longer alive, but it is immortalized by the physical medium of photography. However, this support is also sensitive to degradation. Something to think about as we pursue our illusions and “immortality projects.” Nothing, and I mean nothing, lasts forever. What’s the difference between 500 years and 10,000 years? Not much. It will all go away eventually. We will all die and everyone will be forgotten,

Studium

What is studium? Studium is a Latin word meaning "study," "zeal," "dedication," etc. Studium indicates the factor that initially draws the viewer to a photograph. It refers to the intention of the photographer; the viewer can determine the studium of a photograph with their logical, intellectual mind. Studium describes elements of an image rather than the sum of the image's information and meaning. The studium indicates historical, social, or cultural meanings extracted via semiotic analysis. In other words, you can see references to culture and time in the image. Sometimes they are juxtaposed ideas that conflict with one another or make a cultural or political statement, and sometimes not. This can be an abstract reference or an implied reference as well. Whatever the context, it draws the viewer in.

Punctum

What is punctum? It’s defined as “a small, distinct point.” Barthes uses it to refer to an incidental but personally poignant detail in a photograph that “pierces” or “pricks” a particular viewer, constituting a private meaning unrelated to any cultural code. The punctum points to those features of a photograph that seem to produce or convey a meaning without invoking any recognizable symbolic system. This kind of meaning is unique to the response of the individual viewer of the image.

These are really important ideas to me. As I study my photographs for this work, I find myself employing them as much as I can. Especially punctum. This unspeakable “something personal” that can’t be defined with words is really the essence of any good photograph. If you try to describe it with words, it goes away. I know it may seem antithetical to my position on the importance of narrative, but it’s really not. In fact, it supports the narrative idea fully and wholeheartedly. If the image is well-made and reinforces the story, the punctum will fully support it, even taking it to a new level. Bathes said. “However lightning-like it may be, the punctum has, more or less potentially, a power of expansion.” This is exactly what I’m after. The expansion. This idea transcends photography in a way,

The ultimate effect of punctum is the intimation of death. This is something Barthes realizes in the personal context of his bereavement over the still recent death of his mother. Looking at a portrait of her as a young girl (a picture called “The Winter Garden" that he declined to reproduce in “Camera Lucida”), he sees that her death implies his own. This is death awareness, or consciousness of death. Photography has the power to remind human beings that they will not be alive forever. In fact, you never know when your time is up. It could be today or in 50 years. We never know, but we should bring it from the unconscious to the conscious. If we did that, our world would be a much better place for everyone.

THE GREAT MULLEIN (Verbascum thapsus)

Native Americans utilized this plant for ceremonial and other purposes. It was used as an aid for teething, rheumatism, cuts, and pain. It was also used for a variety of traditional herbal and medicinal purposes for coughs and other respiratory ailments.

Whole-plate platinum/palladium print on Revere Platinum paper from a wet collodion negative.

Chapter By Chapter-Chapter 3 Death Anxiety

Chapter 3: Death Anxiety—This chapter is based on Ernest Becker’s book, "The Denial of Death." The book is quite dense and academically written, but it’s one of the best books I’ve ever read. It literally changed my life.

It’s my burden to unpack the ideas that Becker puts forth and present them to the reader in a way that makes sense and is applicable to their lives. I’ll also show the direct connection between the photographic work and the psychology behind these theories.

I’m writing and organizing, and then rewriting and reorganizing. There are two chapters detailing how these theories work and the underlying psychology. They are: death anxiety and terror management theory.

What is death anxiety? In a few words, it's the desire to stay alive that is in direct conflict, psychologically speaking, with the reality and knowledge that we will die. This causes a sort of cognitive dissonance; it creates unbearable anxiety, terror, and dread. We do everything we can to deny and avoid thinking about our death.

The human animal isn’t terrified of dying—not of the actual moment of death—but of being impermanent (mortal) and dying without significance. Impermanence and insignificance are what create existential terror. That’s what’s unbearable. And this comes from consciousness—the knowledge that we're here. Soren Kierkegaard (1833–1855), a 19th-century Danish philosopher, said that humans can "render themselves the object of their own subjective inquiry." Think about that! That's our big forebrain in action. And psychoanalyst Otto Rank said humans have the capacity "to make the unreal real." This intelligence is a big part of the problem we face. Some think that consciousness is an evolutionary mistake and that we, like all other animals, shouldn’t be aware of our impending deaths.

However, we’ve evolved to cope with this burden by suppressing that death awareness knowledge through self-esteem and using culture. We create “immortality projects.” According to Becker, fear—or denial—of death is a fundamental motivator behind why we do what we do.

Becker said that the real world is simply too terrible to admit. If we didn't have ways of buffering the fear, anxiety, and helplessness over our death and meaninglessness, it would paralyze us and keep us from getting out of bed in the morning. So there is a need to repress it. We use what Becker and all anthropologists call "culture" or "cultural worldview." This "cultural worldview" is a shared reality that we all believe in or subscribe to—a value and belief system that comes from our culture. We find self-esteem through this cultural worldview.

For example, our culture tells us that having a job and getting promotions is a good thing, as is earning more money, driving a certain type of car, or dressing a certain way. If we do these things, our self-esteem is strengthened, and we have a defense or coping mechanism to repress the anxiety that comes from knowing we are going to die. These buffers can be good or bad. That’s why it’s important to be conscious of these ideas and the psychology behind them. Like Freud said, "Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life, and you will call it fate." We can get ourselves out of it by being explicitly aware that we’re in it. Albert Camus said, “…come to terms with death; thereafter, anything is possible." This is the crux of why I'm writing this book and doing this work.

Culture, or cultural worldviews, are defense mechanisms against the knowledge that we will die. Becker argues that humans live in both a physical world of objects and a symbolic world of meaning. The symbolic part of human life engages in what Becker calls an "immortality project." People try to create or become part of something they believe will last forever—art, music, literature, religion, nation-states, social and political movements, etc. Such connections, they believe, give their lives meaning.

Kierkegaard talked about this dread-evoking mystery. He believed that anxiety comes from our knowledge of finitude and meaninglessness. Becker concurs with this point and expounds on it. Kierkegaard said that humans focus their attention on small tasks and diversions that have the illusion of significance—activities that keep people going. If they dwell on the situation too long, they'll bog down and be at risk of releasing their neurotic fear that they are impotent in the world.

That’s a small portion that I’m working on now. You’ll see, in the end, how this all connects to every war, every act of genocide, and every act of evil in the world. Why it happened and why it continues to happen—again, this is the energy of the book, to help people become conscious of this predicament.