Dr. Sheldon Solomon is an experimental social psychologist. He teaches at Skidmore College in New York and is a co-author of the book The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life and one of the creators of terror management theory.

The Big Announcement

Let’s get right to it! I contacted Sheldon Solomon a few days ago to ask him to come back on my YouTube channel for an interview. He said yes! We will arrange something for September. That’s far enough out that everyone can get their questions sorted out to ask him. I know I will. When I have a date and time figured out, I’ll post it. I hope we can talk about the nuts and bolts of these theories in a way that the uninitiated can understand; that’s my biggest desire.

"Rank asked why the artist so often avoids clinical neurosis when he is so much a candidate for it because of his vivid imagination, his openness to the finest and broadest aspects of experience, and his isolation from the cultural worldview that satisfies everyone else. The answer is that he takes in the world, but instead of being oppressed by it, he reworks it in his own personality and recreates it in the work of art." Ernest Becker discusses Otto Rank in The Denial of Death

“Even evil is just the fear of death. Our heroic projects that are aimed at destroying evil have the paradoxical effect of bringing more evil into the world. Human conflicts are life-and-death struggles—my gods against your gods, my immortality project against your immortality project. The root of humanly caused evil is not man’s animal nature, not territorial aggression, or innate selfishness, but our need to gain self-esteem, deny our mortality, and achieve a heroic self-image. Our desire for the best is the cause of the worst. We want to clean up the world, make it perfect, keep it safe for democracy or communism, purify it of the enemies of god, eliminate evil, establish an alabaster city undimmed by human tears, or a thousand-year Reich”

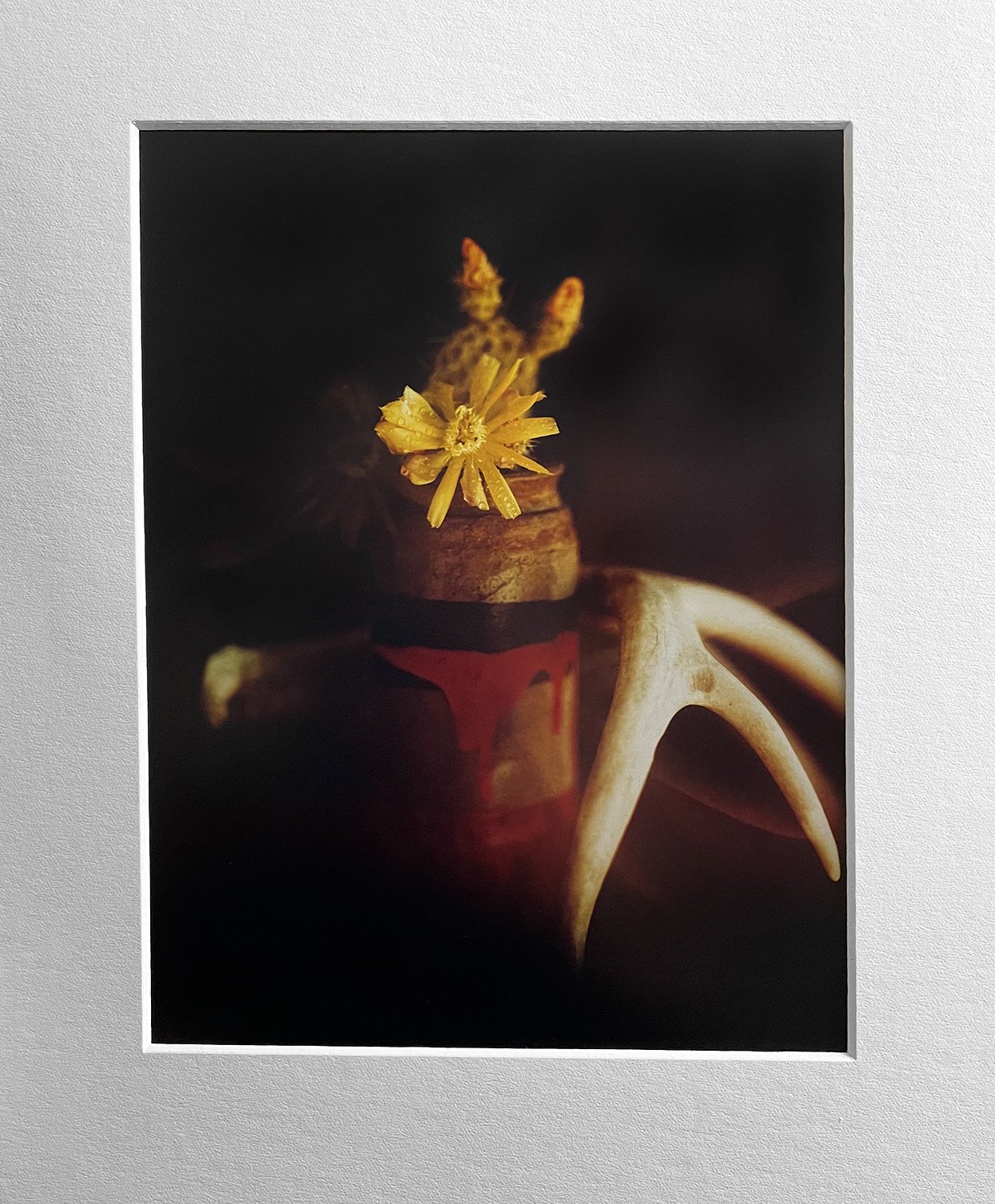

“Wild Peppergrass, Deer Antler, and European Silver,” 10” x10” (25,4 x 25,4 cm) RA-4 Reversal Direct Color Print, July 10, 2023

Native Americans used the bruised fresh plant or a tea made from the leaves to treat poison ivy rash and scurvy. A poultice of the leaves was applied to the chest in the treatment of croup. The seed is anti-asthmatic, antitussive, cardiotonic, and diuretic as well.

My photographs represent an esoteric conflict that’s rooted in our unconscious denial of death. That conflict is the psychological underpinning of the atrocities that happened on this land—the genocide and ethnocide. I’ve connected these ideas through the content of the images: their landscapes, medicinal and ceremonial plants, and some of the symbols that were used on the land. These ideas are represented both symbolically and literally. The cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker said in his 1973 book, The Denial of Death, "Even evil is just the fear of death. Our heroic projects that are aimed at destroying evil have the paradoxical effect of bringing more evil into the world. Human conflicts are life-and-death struggles—my gods against your gods, my immortality project against your immortality project. The root of humanly caused evil is not man’s animal nature, not territorial aggression, or innate selfishness, but our need to gain self-esteem, deny our mortality, and achieve a heroic self-image. Our desire for the best is the cause of the worst. We want to clean up the world, make it perfect, keep it safe for democracy or communism, purify it of the enemies of god, eliminate evil, establish an alabaster city undimmed by human tears, or a thousand-year Reich." Becker’s ideas perfectly describe the reasons for the xenophobia and genocide of the Tabeguache and all other indigenous people all over the world and throughout history.

According to Becker, individuals develop what he called "immortality projects" as a means of overcoming the terror of death. These projects are essentially belief systems or ideologies that provide a sense of meaning, purpose, and significance to our lives, offering the promise of immortality in some form. Examples of immortality projects can be found in religion, nationalism, political ideologies, a creative life, and other forms of collective identity.

Becker argues that conflicts between individuals and groups arise from clashes between these immortality projects. People invest their self-esteem and identity into their projects, and when these projects are threatened or challenged, it triggers a fear of death. This fear, in turn, leads to defensive responses, including aggression and violence, as individuals strive to protect and preserve their immortality projects.

In this context, Becker suggests that even acts that are commonly labeled as evil can be understood as manifestations of the fear of death. When people feel threatened by opposing ideologies or beliefs, they may engage in destructive actions to defend their immortality projects. Paradoxically, the very attempts to eliminate evil and establish a perfect world can lead to more conflict and suffering because they stem from our fear of death and the need to maintain a heroic self-image. This is a perfect analogy of what my project is about.

Ultimately, Becker argues that the root cause of humanly-caused evil is not inherent human nature but rather our deep-seated psychological need to gain self-esteem, deny our mortality, and construct a heroic self-image through immortality projects. Our pursuit of the best, the ideal, and the perfect can inadvertently result in the worst outcomes, perpetuating a cycle of conflict and suffering. Most atrocities are committed or acted out from this viewpoint.

While I find this very compelling, it is important to note that these ideas put forth by Ernest Becker are just one perspective on the nature of evil and human behavior. Alternative theories and philosophies provide alternative explanations, and the subject of evil is complex and multifaceted, and academics and thinkers from various disciplines continue to explore and debate it.

A Recent Interview on “Tin Questions”

I was interviewed by Chad Shyrock from Tin Questions; you can listen to that here if you’re interested.