People wonder why terrible things happen in the world. I’ve had a preoccupation with this question for decades. It’s what made me pick up a camera all those years ago. Why do certain people or certain groups fall victim to horrible events? If you follow what's happening in Ukraine today and in many other parts of the world, you know what I mean. It’s heart-wrenching.

These events can be very personal, or they can be global. They usually deal with the same thing; genocide, ethnocide, loss, tragedy, and injustice. And most of the time, they are about "us" and "them." I would suggest that because we fear death, it is in our nature to always find "the other" to blame, use as a scapegoat, humiliate, demean, and ultimately kill.

And I would argue that “the other" challenges our psychological buffers against existential anxiety; we are left defenseless. This is why we can’t get along with people who are different from us. This is the definition of death anxiety. It’s our inability to psychologically deal with the instinct to stay alive and the knowledge that we’re going to die.

One of the biggest problems is a lack of self-awareness. For most people, death is a vague abstraction that doesn’t pertain to them. William James said, “There’s a panic rumbling beneath the surface of consciousness.” I can see that statement clearly when I look at the history of the world and even current events. I can see it in people and they don’t even recognize it.

Ernest Becker said in his book, Escape from Evil, "In this view, man is an energy-converting organism who must exert his manipulative powers, who must damage his world in some ways, who must make it uncomfortable for others, etc., by his own nature as an active being. He seeks self-expansion from a very uncertain power base. Even if man hurts others, it is because he is weak and afraid, not because he is confident and cruel. Rousseau summed up this point of view with the idea that only the strong person can be ethical, not the weak one."

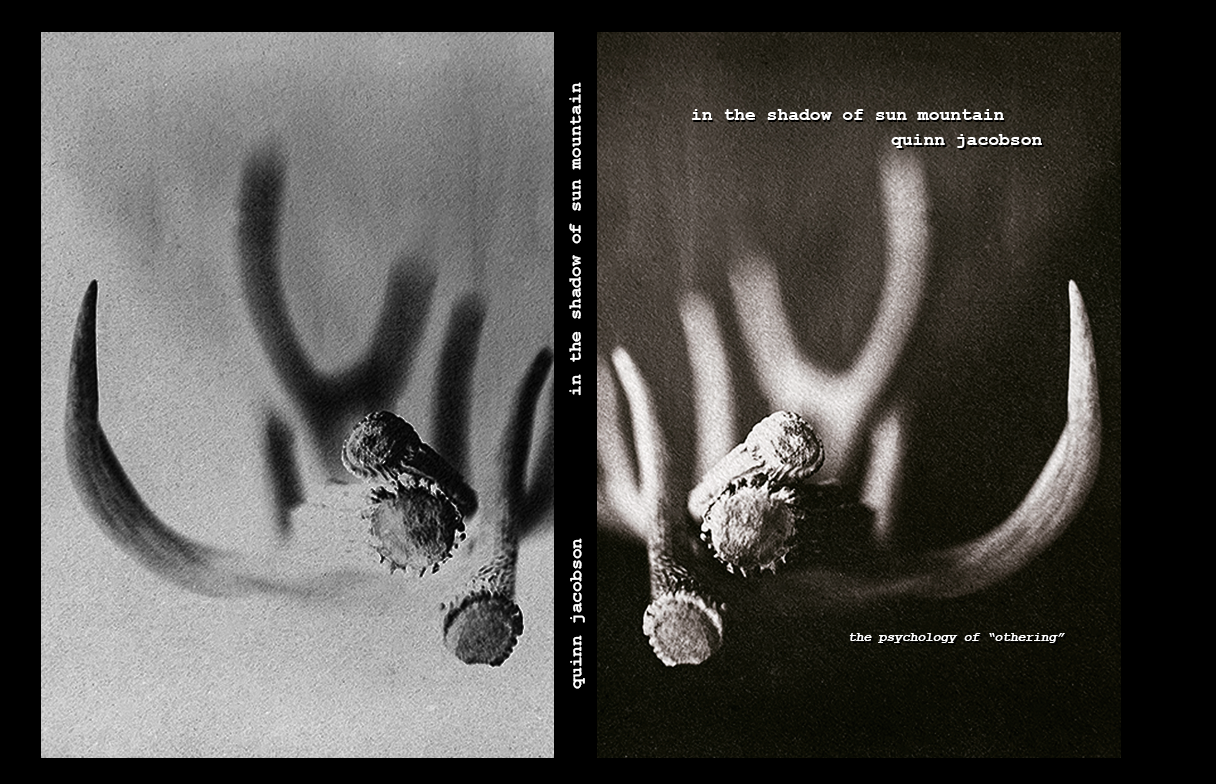

My photographs are a way of communicating these ideas in more poetic and lyrical ways than words can. They are about ideas and emotions surrounding death anxiety and terror management theory—subtle visual cues that are difficult to describe in words.

This work is about the Tabeguache-Ute people and many other groups throughout history that have been victims of the paradoxical human condition. It’s about their land, their plants and animals, and some of the symbolism and objects they used here. At least, that’s what the images are about on the surface. In reality, they are about the "residue," or what’s left here, visually representing the psychology of the land and objects. Moreover, it's about why it happened. It attempts to answer the big questions surrounding human behavior and "the other." This work is as much about psychology as it is about photography.

The pictures are not a romanticized version of indigenous people. There are no images of people at all in this work. I’ve made a conscious decision not to photograph people. I’m not interested in promoting the white, Eurocentric view of Native Americans. I’m not interested in trying to show their "Indianness." I see this as another way of keeping them victims of the colonial gaze. It’s almost a form of continued ethnic cleansing. There is so much baggage there to unpack, and most people don’t have the skills or knowledge to do it. These kinds of images carry that weight, whether the creator or viewer are aware of it or not.

“When the angel of death sounds his trumpet, the pretenses of civilization are blown from men’s heads into the mud like hats in a gust of wind.” – George Bernard Shaw