“If you wish to become a philosopher, the first thing to realise is that most people go through life with a whole world of beliefs that have no sort of rational justification, and that one man’s world of beliefs is apt to be incompatible with another man’s, so that they cannot both be right. People’s opinions are mainly designed to make them feel comfortable; truth, for most people is a secondary consideration.”

― Bertrand Russell, The Art of Philosophizing and other Essays (1942)

I really enjoy the study of philosophy (the love of wisdom). Over the years, I’ve read a lot of it. I’ve read everything from the old Greeks and Romans to modern thinkers, and I suppose I know just enough to be dangerous. In reality, I really don’t know much at all. I’ll save that for another time.

After reading Becker, I have a different view on philosophy. Now, it feels like the major philosophical theories are only halfway there or not complete; they feel unfinished. Russell’s quote (above) is a good example. While I completely agree with it, it doesn’t finish the thought. It falls short without Becker’s theories to complete it. All philosophy feels this way to me now: always referring to the answer but never really answering.

I'm not saying I disagree with the major philosophers about life and ideas on the human condition; on the contrary, however, I believe Becker's ideas are at the top of the philosophical pyramid. Everything, including all human behavior and thought, comes below his theories. His ideas and theories answer questions about the human condition. And they answer them definitively—at least in my mind, they do.

I know this is a bad analogy, but it’s a lot like treating the cough when you have a cold and not addressing the virus. That’s how it feels to me. I want to address the virus, not the cough. Becker gets to the heart of these matters.

I’ve always been a person who seeks the truth. I want logic and rational thought in my life. I’m not a believer in magic or superstition. In the context of life philosophy, those things seem trivial and unimportant. If there are no answers to the "big" questions, I’ll live with that. I don’t have the desire to make something up to say that I know the answer.

A good example of this today is the number of people who believe in conspiracy theories. These are "answers" that attempt to satisfy complicated questions or outright fantasies. The people who believe in these kinds of things feel empowered because they know something that most don’t. Feelings and opinions are irrelevant to me in the context of facts. I want evidence for positions and ideas put out there for discussion. This is where Russell’s quote is spot on.

I digress.

So let us address the virus, not the cough, of life's big questions. Let’s be clear and definitive when we have evidence for our position. Becker gives us those tools. He answers the most vital and important questions in life through his theories. And Solomon, Greenberg, and Pyszczynski go on and give us empirical evidence to show Becker’s theories are correct.

“We don’t want to admit that we are fundamentally dishonest about reality, that we do not really control our own lives. We don’t want to admit that we do not stand alone, that we always rely on something that transcends us, some system of ideas and powers in which we are embedded and which support us. This power is not always obvious. It need not be overtly a god or openly a stronger person, but it can be the power of an all-absorbing activity, a passion, a dedication to a game, a way of life, that like a comfortable web keeps a person buoyed up and ignorant of himself, of the fact that he does not rest on his own center. All of us are driven to be supported in a self-forgetful way, ignorant of what energies we really draw on, of the kind of lie we have fashioned in order to live securely and serenely. Augustine was a master analyst of this, as were Kierkegaard, Scheler, and Tillich in our day. They saw that man could strut and boast all he wanted, but that he really drew his “courage to be” from a god, a string of sexual conquests, a Big Brother, a flag, the proletariat, and the fetish of money and the size of a bank balance.”

—Ernest Becker

“Rocky Mountain Cotton Grass—Blown Away"—a cyanotype on waxed vellum paper. The wind is blowing away the last seeds of the Rocky Mountain cotton grass. November, 2022.

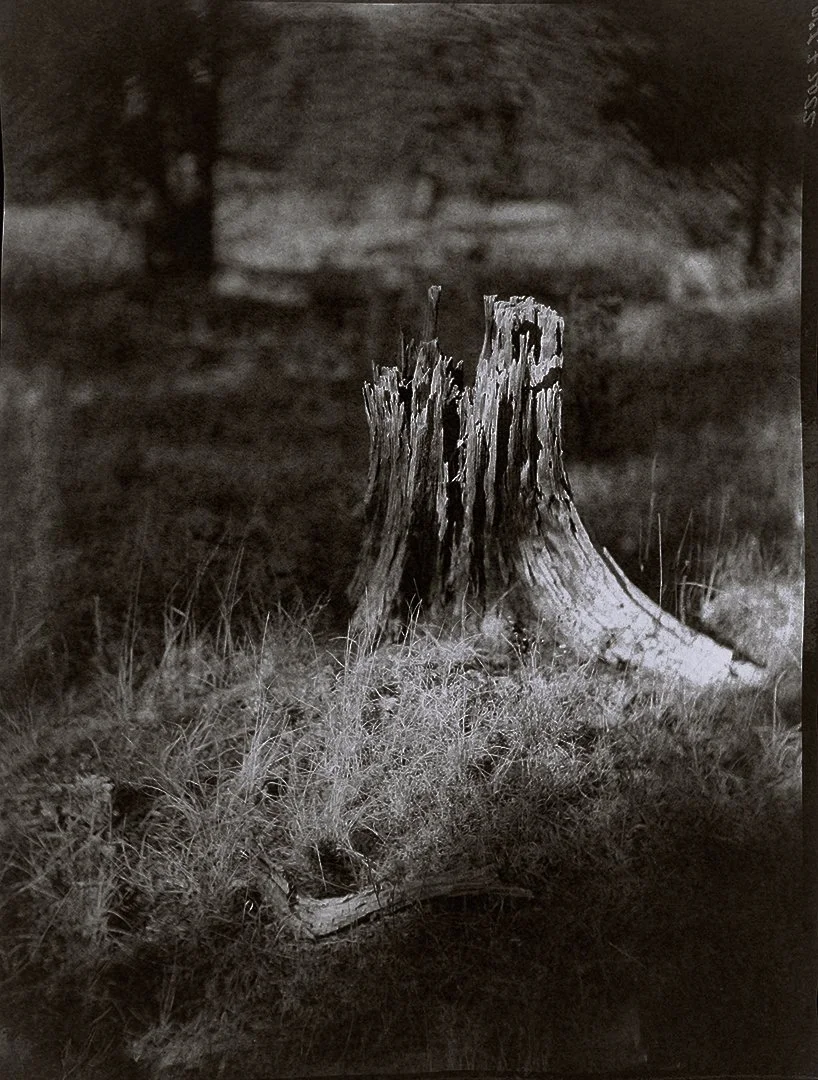

The last light of the day sets on an old Ponderosa Pine tree stump. Many years ago, it was struck by lightning.

Almost 40 paper negatives (calotypes) I’ll make more of these over the winter. This is a good start for what I want to do for the project.