Pretty Pictures, The Technical Versus The Conceptual, and the Masses: Try Something New

We lean so heavily on "pretty" (aka "chocolate box") pictures or "process photography" pictures that we forget about narrative, meaning, and intent—all of the things that really make photographs and storytelling interesting and meaningful. This is not a new topic. I've been preaching this message for years on my YouTube channel, in my books and workshops, and anywhere else I can engage in conversation about making art and photography.

Let’s be honest; most photography is easy to forget. We see so much of it that it becomes less interesting or engaging. And it’s not anchored to anything meaningful that people can connect to. I define meaningful as something weighty in life—work that contains life lessons that we can use to become better people in some way—to be an asset to the world, not a liability.

I’m not talking about technical prowess either. A lot of times, this is conflated with meaning or importance. People love to see big photographs or rare processes. The content of the photograph seems irrelevant, and most of the time, the process and size have little or nothing to do with the subject matter.

The technical work is easy to talk about. It’s safe and universally appealing. This demographic always wants to know about the equipment you're using—what camera, what lens, etc. I always offer the Ernest Hemingway analogy. I've never heard anyone ask what kind of typewriter he used to write "The Old Man and the Sea." Why is that? It's very similar to this obsession with gear and equipment, processes, and size.

They connect technically, but in no other meaningful way. The emphasis appears to be solely on the technical, with no regard for the conceptual or narrative content. I believe they connect to these images because they want to replicate what they see and appeal to the masses to get "likes" and "views" on social media. They want the attention and adulation simply for carrying out a technical process or for owning expensive or rare equipment, period. This seems trivial and mechanical. Do you see why this type of photography is everywhere and why you see it so often? It's a feedback loop, and it’s derivative.

There’s a logical fallacy called Argumentum ad Populum (an appeal to popularity, public opinion, or the majority). It’s an argument, often emotionally laden, for the acceptance of an unproven conclusion by adducing irrelevant evidence based on the feelings, prejudices, or beliefs of a large group of people—the masses. Based on social media, this is how I see most photography today. It’s rare that we get a body of work that’s connected to a narrative or has substance, meaning, or any of the other attributes that I’ve mentioned. The pull of social media is too strong—the desire or need to be accepted and “liked” is powerful (see Becker and self-esteem). The one-off, cliched images are what the masses want. I believe we can do better. We can raise the bar. I know we can. I’m going to try my best to model this behavior with this project.

"The immediate man - the modern inauthentic or insincere man - is someone who blindly follows the trends of society to the dot. Someone who unthinkingly implements what society says is ‘right.’ He recognizes himself only by his dress,...he recognizes that he has a self only by externals. He converts frivolous patterns to make them his identity. He often distorts his own personality in order to 'fit into the group.' His opinion means nothing even to himself, hence he imitates others to superficially look "normal." - Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death

Having said that, I will tell you that I’m going all in on this work (In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of “Othering”). I’m going to push the boundaries as much as possible. I even want to try to transcend photography in some ways. I want the viewer to remember the message in the story—the "meat," if you will. I want them to connect in a real way to the narrative and ideas and to put that proverbial pebble in their shoe.

Trying To Do Something Different

Most of you who read my posts regularly know that this is a unique project. I might even assert that it hasn’t been done before. I’m combing art, psychology, philosophy, theology, history, and existential anxiety to talk about human behavior. This is a distinctive combination of the humanities and art. I haven’t seen anything like it in my research.

I say that with the caveat of Otto Rank’s book, “Art and Artist.” This book is a difficult and dense read. Rank’s ideas would relate most closely to what I’m trying to do, at least the ideas and execution, or simply dealing with the creative life as a psychological defense against the knowledge of death. But even this is in a different context. In his book, he contemplated the creative type of man, who is the one whose "experience makes him take in the world as a problem... but when you no longer accept the collective solution to the problem of existence, then you must fashion your own... The work of art is... the ideal answer...”

All of this motivates me, and it makes it exciting to do the work.

The impetus behind this work is psychology. The theories of Ernest Becker are at the core of it. There are a lot of other people who have influenced the work, but as far as the main component goes, it’s Becker. The terror management theory is just as important. TMT gives evidence for Becker’s theories, so I’m leaning heavily on TMT too. I will include all of the references and resources in the book. You’ll see how vast and rich they are.

I believe these are very important ideas, maybe the most important I've ever heard. They explain so much and answer so many questions, questions that I’ve carried for 50 years. My hope is that the reader or viewer will take away positive ideas for making the world a better place. This is not about being negative or pessimistic. These ideas should nudge you toward celebrating every day we are above ground and being humble and grateful to be alive. The most valuable things are finite and have a relatively short lifespan. That describes humanity very well.

“In the Shadow of Sun Mountain: The Psychology of ‘Othering’”

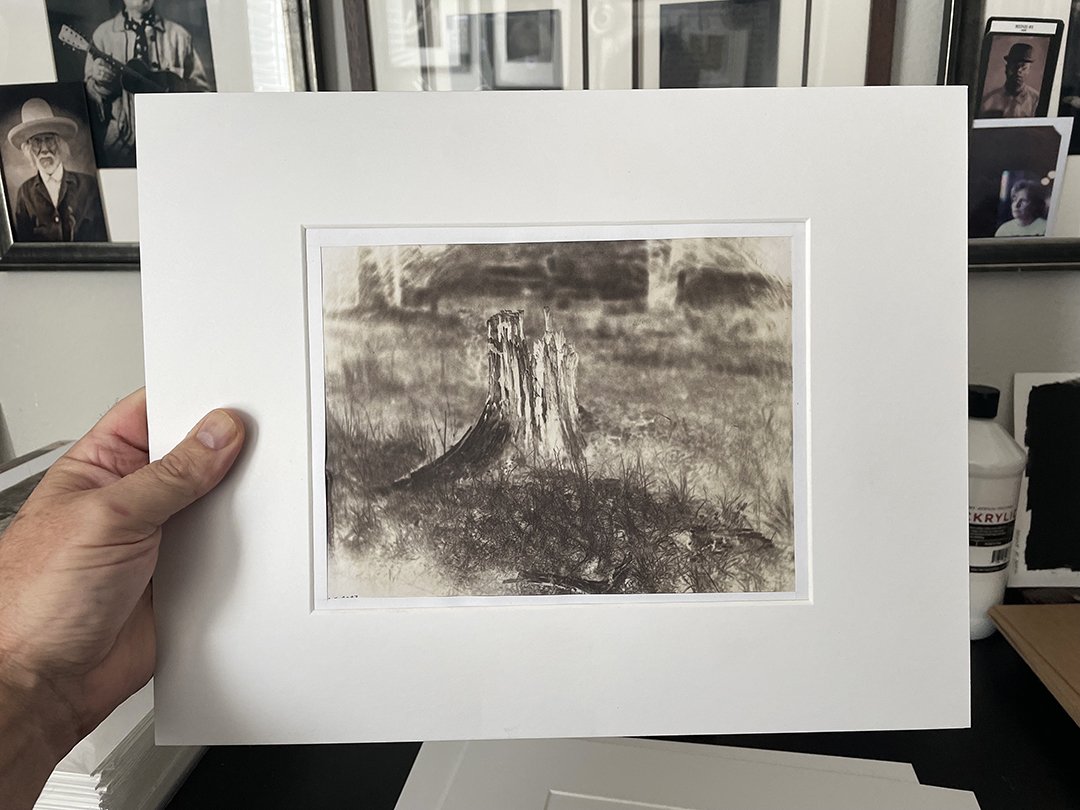

My intention is to create a psychological connection between my photographs of the land, plants, and symbols of the Tabeguache-Ute and the historical event of colonization. I'm providing psychological evidence as to why atrocities like these and so many others happen. It’s based on human awareness of death, or death anxiety.

While I’m using a specific historical event, the ethnocide and genocide of Native Americans, specifically the Tabeguache-Ute, this could be any number of similar events in history. I’m using psychology, philosophy, theology, history, and art (19th-century photography) to tell the story of "othering" or the psychology of "othering."

It’s not just telling a story of historical atrocities. It’s describing in detail the psychological underpinnings of "othering." I'm answering the questions about why these kinds of things happen, and I’m backing my claims and assertions with empirical evidence. I’m asking and answering the “big questions:” Why do we marginalize certain groups of people? Why are we threatened by people who are different from us? Why do we start wars? Why do we commit genocide? Why are we ignoring climate change? Etcetera, etcetera. I'm attempting to answer those questions with this body of work and book.

I’m addressing this subject somewhat academically. In other words, I’m drawing on the writing and research of social psychologists, scientists, philosophers, theologians, and anthropologists. I’m also referencing a lot of writers who would be considered artists—playwrights, novelists, and poets. My approach to this work is interdisciplinary because this topic requires a wide range of information to be understood.

I live on this land now. In a lot of ways, I struggle with it. I understand what happened here and why. I can't change the past. I wish I could. What I can do is offer or extend the notion of self-examination. These events, and many others like them, should not be viewed as "in the past," but as something that can happen to anyone at any time. Consider your own psychological pathology of existential terror. Consider what psychological defenses, or buffers, you are using to repress the anxiety. Are they positive? Are they an asset or a liability to the world? It's a lot more difficult to create a great work of art than to post insults and argue on social media. They're both defenses, or buffers; one is an asset, and the other is a liability.

Consciousness is the Parent of All Horror: It’s the Worm at the Core

A more detailed definition would be that my work is about human consciousness. The knowledge that we exist and the consequences of that knowledge—knowing that we’re going to die—are too much for us to psychologically handle. It truly is the worm at the core. Sheldon Solomon said, “The thing that renders us unique as human beings is that we’re smart enough to know that like all living things, we too will die. The fear or anxiety that is engendered by that unwelcome realization, when we try to distance ourselves from it or deny it, that’s when we bury it under the psychological bushes as it were, it comes back to bear bitter and malignant fruit, on the other hand folks who have the good fortune by virtue of circumstance or their character or disposition to really be able to explicitly ponder what it means to be alive in light of the fact that we are transient creatures here for a relatively inconsequential amount of time; I buy the argument theologically, philosophically, as well as psychologically and empirically, that can bring out the best in us, and that our most noble and heroic aspirations are the result of the rare individual, who’s able to live life to the fullest, by understanding as Heidegger put it, that we can be summarily obliterated not in some vaguely unspecified future moment but at any second in our lives.”

When he says, "It comes back to bear bitter and malignant fruit," that sums up my central point about this work: answering the questions about the decimation of the Tabeguache-Ute and millions of other human beings. Why do these kinds of things happen? What are the solutions to preventing these kinds of things? These and other questions about human behavior are addressed by this psychology.

Thomas Ligotti’s book, “The Conspiracy Against the Human Race,” says, "consciousness is the parent of all horror." He quotes quite a lot from Peter Zapffe's 1933 essay, "The Last Messiah," referring to anti-natalism and pollyannaism, or the Pollyanna Principle. His position, because of this knowledge, states that it would have been better to have never existed in the first place. He encourages humans to stop procreating. The end of Zapffe’s book also draws this conclusion. He posits that human consciousness was an evolutionary mistake. This sentiment is echoed throughout pessimistic philosophy; it’s not new. On one hand, it is difficult to argue against—the pain and suffering in the world can’t be fathomed. If you read Zapffe’s book, you’ll know what I mean.

"The life of the worlds is a roaring river, but Earth's is a pond and backwater.

The sign of doom is written on your brows—how long will ye kick against the pin-pricks?

But there is one conquest and one crown, one redemption and one solution.

Know yourselves—be infertile and let the earth be silent after ye."

Peter Zapffe, The Last Messiah

A Different Perspective

Richard Dawkins, in his book Unweaving the Rainbow: Science, Delusion, and the Appetite for Wonder, said, “We are going to die, and that makes us the lucky ones. Most people are never going to die because they are never going to be born. The potential people who could have been here in my place but who will in fact never see the light of day outnumber the sand grains of Arabia. Certainly those unborn ghosts include greater poets than Keats, scientists greater than Newton. We know this because the set of possible people allowed by our DNA so massively exceeds the set of actual people. In the teeth of these stupefying odds it is you and I, in our ordinariness, that are here. We privileged few, who won the lottery of birth against all odds, how dare we whine at our inevitable return to that prior state from which the vast majority have never stirred?“

You can have a different perspective on these ideas, but the bottom line returns to the knowledge of our impending deaths and the effects that has on our behavior. There is enough evidence to show that, while there are a lot of things to take into consideration, mortality salience drives most human behavior. Exploring that idea is what I’m most interested in for this body of work.