“Art is essentially the affirmation, the blessing, the deification of existence.” - Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power, 1901

There are some very interesting philosophies in our world today concerning the way we live and the cycles we go through as human beings. I want to address two of them in this essay.

HOMO MORTALIS (MORTAL MAN)

The first is from the book, “The Worm At The Core: The Role Of Death In Life,” by Jeff Greenberg, Tom Pyszczynski, and Sheldon Solomon. If you’ve read other essays that I’ve posted, I’m sure you recognize the reference.

They have suggested that the foreknowledge of our own death may be what most widely separates us from other mammals. Perhaps we might even be more aptly called Homo mortalis rather than Homo sapiens. They write, “There is now compelling evidence that, as William James suggested a century ago, death is indeed the worm at the core of the human condition. The awareness that we humans will die has a profound and pervasive effect on our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in almost every domain of human life—whether we are conscious of it or not.”

It’s a transformative and fascinating theory. It’s based on robust and groundbreaking experimental research, and it reveals how our unconscious fear of death powers almost everything we do, shining a light on the hidden motives that drive human behavior. More than one hundred years ago, the American philosopher William James dubbed the knowledge that we must die "the worm at the core" of the human condition. In 1974, cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker won the Pulitzer Prize for his book The Denial of Death, arguing that the terror of death has a pervasive effect on human affairs. Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg, and Tom Pyszczynski clarify these theories with wide-ranging evidence of the many ways the worm at the core guides our thoughts and actions, from the great art we create to the devastating wars we wage.

The Worm at the Core is the product of twenty-five years of in-depth research. Drawing from innovative experiments conducted around the globe, Solomon, Greenberg, and Pyszczynski show conclusively that the fear of death and the desire to transcend it inspire us to buy expensive cars, crave fame, put our health at risk, and disguise our animal nature. The fear of death can also prompt judges to dole out harsher punishments, make children react negatively to people different from themselves, and inflame intolerance and violence.

But the worm at the core need not consume us. Emerging from their research is a unique and compelling approach to these deeply existential issues: terror management theory. TMT proposes that human culture infuses our lives with order, stability, significance, and purpose, and these anchors enable us to function from moment to moment without becoming overwhelmed by the knowledge of our ultimate fate. (edited/Goodreads)

I’ll write more about Terror Management Theory (TMT) in the future. It does provide some insight into managing death anxiety. Becker clearly laid out these ideas; the worm at the core details them and provides empirical evidence for them.

THE FOURTH TURNING (THE ‘CRISIS’ PHASE)

It may have been better to separate these essays into two parts. As I was thinking about writing these, I realized that they are connected in so many ways that I felt compelled to join them in one essay. I think you’ll see what I mean.

The authors, William Strauss and Neil Howe, wrote a book in 1997 called, “The Fourth Turning; An American Prophecy—What the Cycles of History Tell Us About America’s Next Rendezvous with Destiny".

Looking back to the dawn of the modern world, The Fourth Turning reveals a distinct pattern in human history—cycles lasting about the length of a long human life, about 80-90 years. Each cycle is composed of four “turnings,” and each turning lasts the span of a generation (about 20 years). There are four kinds of turnings: High, Awakening, Unraveling, and Crisis, and they always occur in the same order. (from The Fourth Turning site).

In a nutshell, this book is about how the cycles of history (at least in American history) repeat themselves about every 80–90 years. There are “turnings” about every 20–25 years—four of them in each cycle. If you start with the American Revolution (1775), then the American Civil War (1861), The Great Depression, and World War 2 (1942), that leaves you sitting here in 2022, in the middle of the “crisis” era. These are all about 80-90 years apart. According to Howe, this crisis period will last until about 2030. After that, we’ll gradually enter a “high” period again. These “turnings” are like the seasons; spring, summer, autumn, and winter. We’re in the winter phase.

This is a fascinating concept, and our history tends to show its validity. There are some difficult turnings within the overall cycle. It seems we’re in one of those today. In fact, I would argue that we are. The good news is that in times of "crisis,” turning, historically, we’ve done some incredible things. The social security programs were all created in the 1930s—the depression era—as well as the American Civil War, which brought us the establishment of public education. There are some good things that come from it. There are also some very terrible things that come from these turnings.

In my opinion, death anxiety and these turnings are directly related. They sit together well. In fact, I would say they complement one another if I could use that term. Think of it as individuals acting out, or on, our immortality projects, and collectively, acting out, or on, the turnings in the generation we belong to; i.e., Boomers, Gen X, Millenials, etc. This makes a lot of sense to me. I can clearly see the death denial theories tying into the cycles of history. They provide different types of immortality projects for people of different generations and times, but it still comes back to the fact that death anxiety motivates these desires.

I would recommend reading the book or even watching some YouTube videos on the topic. It will really give you something to think about. It’s not religious prophecy or prophets, or anything like that. It’s based on the history of this country and the patterns that stand out. Almost undeniable. If this is, in fact, correct, we’re in for some rough waters ahead as a country and people. Forewarned is forearmed.

"Fourth turnings almost always end in total war." Neil Howe

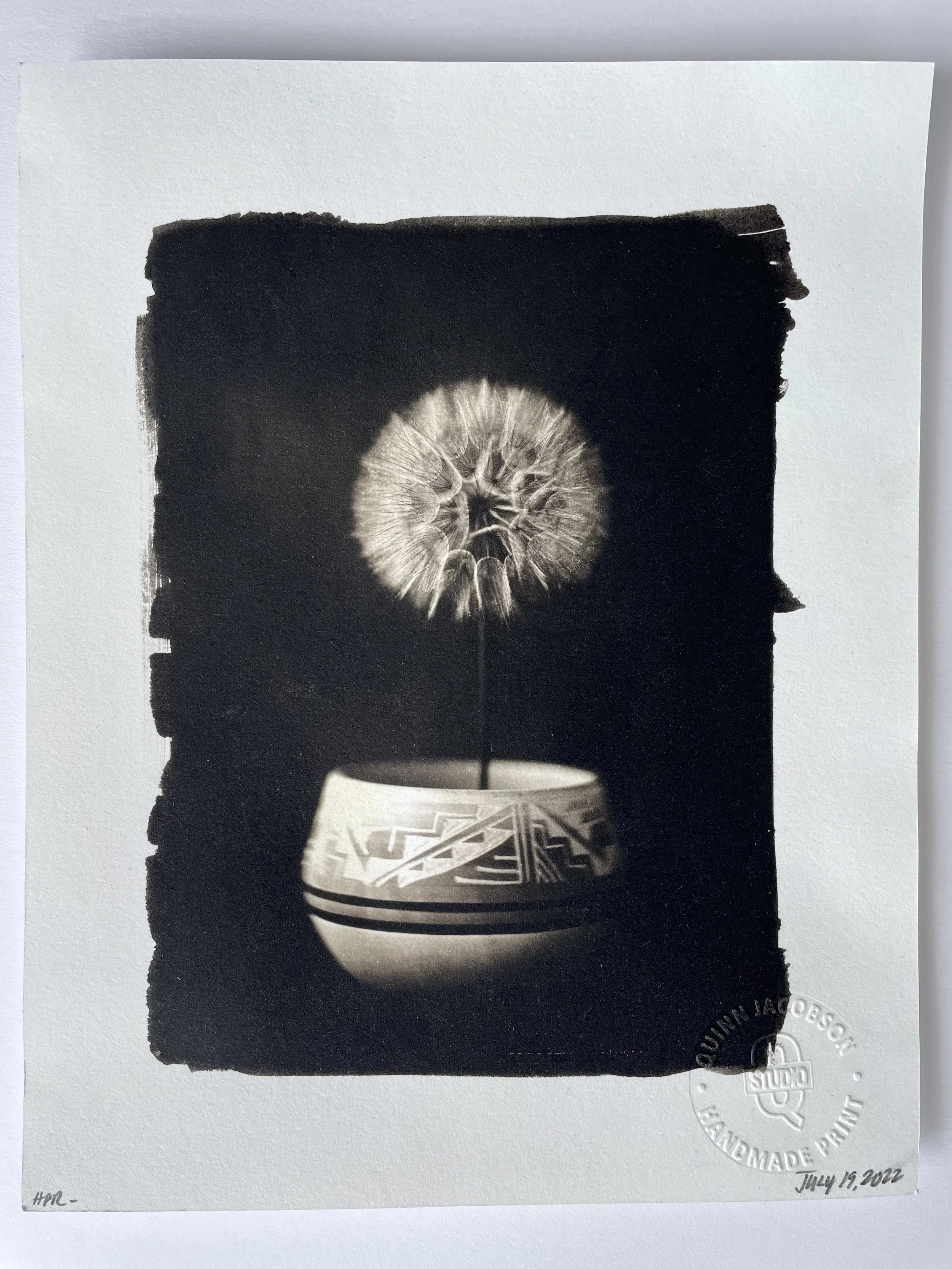

Western Goat’s Beard - a photogenic drawing - No. 2

Western Goat’s Beard - a Palladiotype print from a wet collodion negative.