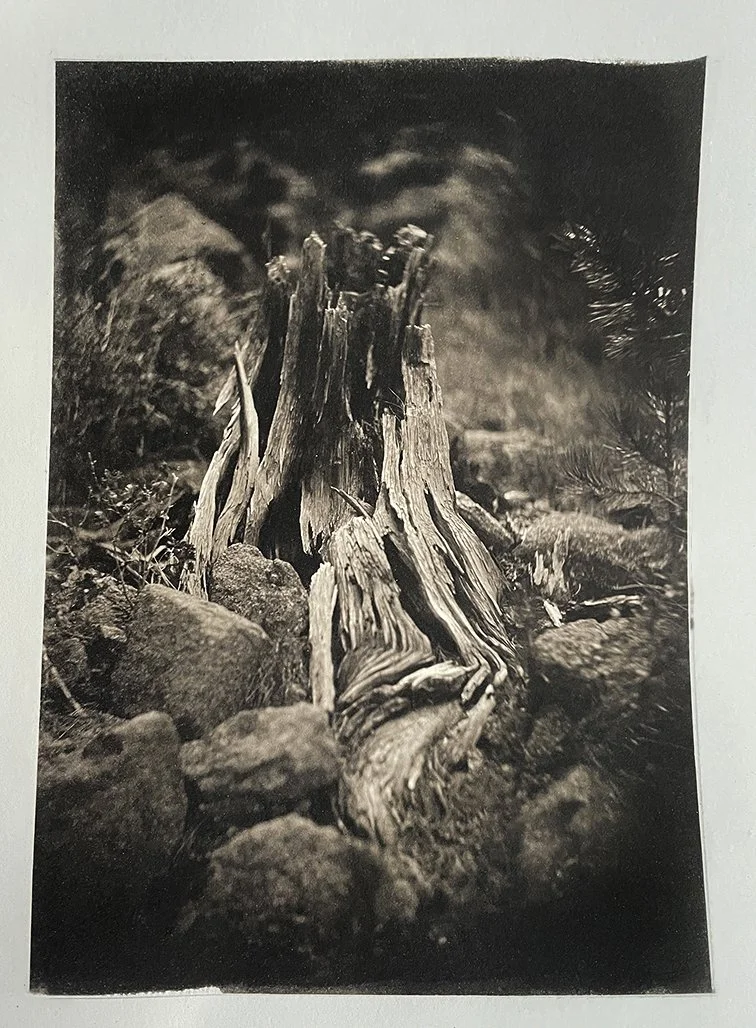

Morning walks with Jeanne get me to reflect on topics I've been reading about and researching concerning my project. I always come across things that make me think or motivate me. The cool mountain air and the beauty of the changing seasons are lovely; it’s a great environment to meditate on what I’m trying to do. If there’s something that really hits me hard, when I get home, I’ll head to the darkroom and begin the process of making a photograph. Today was one of those days.

It works well on some days and not so well on others. Regardless, I enjoy the entire creative process. It's challenging trying to make visuals that support the concepts or ideas I have in my head and heart. Symbolism is my staple for this work. Yes, the content is "real" and represents what it is, but my desire is to take it to a deeper conceptual level. We’re symbolic in so many ways, and we create lives that symbolize something they’re not. I’m fascinated and intrigued by these kinds of ideas.

I love the painterly quality and color of the cyanotype (below). I’m going to explore some other organic compounds to tone these prints. I used tannic acid and gallic acid on this one. A lot of people don’t like how the tannic acid stains the paper. I like it. It adds a sense of age to the print. It feels like something else—and it kind of transcends photography.

Plate #121-Whole plate toned cyanotype from a wet collodion negative.

Homo aestheticus: where art comes from and why.

All human societies throughout history have given a special place to the arts. Even nomadic peoples who own scarcely any material possessions embellish what they do own, decorate their bodies, and celebrate special occasions with music, song, and dance. A fundamentally human appetite or need is being expressed—and met—by artistic activity. As Ellen Dissanayake argues in this stimulating and intellectually far-ranging book, only by discovering the natural origins of this human need of art will we truly know what art is, what it means, and what its future might be. Describing visual display, poetic language, song and dance, music, and dramatic performance as ways by which humans have universally, necessarily, and immemorially shaped and enhanced the things they care about, Dissanayake shows that aesthetic perception is not something that we learn or acquire for its own sake but is inherent in the reconciliation of culture and nature that has marked our evolution as humans. What "artists" do is an intensification and exaggeration of what "ordinary people" do, naturally and with enjoyment—as is evident in premodern societies, where artmaking is universally practiced. Dissanayake insists that aesthetic experience cannot be properly understood apart from the psychobiology of sense, feeling, and cognition--the ways we spontaneously and commonly think and behave. If homo aestheticus seems unrecognizable in today's modern and postmodern societies, it is so because "art" has been falsely set apart from life, while the reductive imperatives of an acquisitive and efficiency-oriented culture require us to ignore or devalue the aesthetic part of our nature. Dissanayake's original and provocative approach will stimulate new thinking in the current controversies regarding multicultural curricula and the role of art in education. Her ideas also have relevance to contemporary art and social theory and will be of interest to all who care strongly about the arts and their place in human, and humane, life.

Source: Publisher

Dissanayake, E. (1992). Homo aestheticus: where art comes from and why. New York: Free Press.