“You already know enough. So do I. It is not knowledge we lack. What is missing is the courage to understand what we know and to draw conclusions.”

― Sven Lindqvist, "Exterminate All the Brutes": One Man's Odyssey into the Heart of Darkness and the Origins of European Genocide

Have you seen the four-part series from Raul Peck called “Exterminate All The Brutes”? It’s based in large part on Sven Lindqvist’s book of the same name. And Lindqvist based his book on Joseph Conrad’s book, “Heart of Darkness.” Francis Ford Coppola’s film, “Apocalypse Now,” was based on Conrad’s book, too. Whew! That’s quite a lineage! There is very powerful content in all of it!

I highly recommend reading both Conrad’s book and Lindqvist’s book. They deal with the genocide in Africa (committed by the Europeans)—colonial genocide. Conrad’s story is about what happened in the Congo, and Lindqvist’s book gets at the root of the genocide in Africa as a whole. It’s a modern-day diary or travelogue in a way too. And definitely check out Peck’s piece on HBO. It’s an amazing 4-hour series. It’s so well-made, accurate, and very moving that I think it should be mandatory viewing for every American and European. I recommended it last year on my YouTube show. I used to do recommended reading and recommended watching every week. Doing that kept me in the books and films. I found some really great material.

My work has always confronted and questioned how marginalized communities are treated. This is not new territory for me, but the information that I’ve been studying over the past few years has really taken it to a new and solid place. Ernest Becker and Sheldon Solomon have given me a new set of tools to work with. These resources, among many others, have informed and supported my work in big ways. For many years, I’ve wrestled with the real history of America and Europe—the places of my heritage—and how we treat (and have treated) “the other.”

I lived in Germany for five years and tried my best to come to terms with what happened there by making photographs. I studied, traveled, and explored everything I could that was related to that history. I ended up making a body of work called “Vergangenheitsbewältigung.” Unfortunately, I never got to address the core reasons for what happened there. If I could go back now, I would be able to square that circle of confusion. For the most part, I would be able to answer that question today with quite a bit of confidence.

Now, I live on the land of the Ute/Tabeguache and am trying to do the same thing, but armed with powerful and enlightening information. The information I’m in possession of now is based on empirical evidence—it’s the best answer we have to this enormous problem. It’s a good feeling. And it empowers me and drives the work in a certain direction—in an authentic direction—that motivates me to share these ideas with my brothers and sisters of the world. That’s very important to me and one of the main reasons the work is being done. I’m more concerned with the viewer understanding the theories than liking the photographs, Both would be ideal, but the theory is far more important than the pictures.

I have a lot of life experience that lends itself to expressing ideas in a certain way. I’m not quite sixty years old yet, but I can see why they say you make your best work at this stage of your life. I get it. There seems to be an opening or willingness here that I’ve never really experienced before. There’s also a certain sense of maturity in the relationship to the photographs, or making the photographs. There’s an unrestrained passion to make work that is interesting and powerful in your eyes, regardless of what anyone else thinks. Like life itself, there’s a beautiful freedom that I’ve never fully experienced before. I’m very grateful for it.

Currently, I’m writing an introduction for my book and working on some essays for it. I’ve completed my artist’s statement and have about 15 essays so far to include in the book. I feel good about the direction this is going.

It’s winter here in the Rocky Mountains now. My book project gives me plenty to work on when the snow flies and it’s cold out. We do get nice sunny days quite often, so I’ll continue to make pictures and prints, but it will be less often and not in any quantity. I had a great year working on this project. It was everything and more than I expected. If I get another year like this, I’ll have something exciting to work with. I’m in no hurry to finish. In fact, I only give myself general guidelines and no real timeline. I think I’ll finish next year, but who knows?

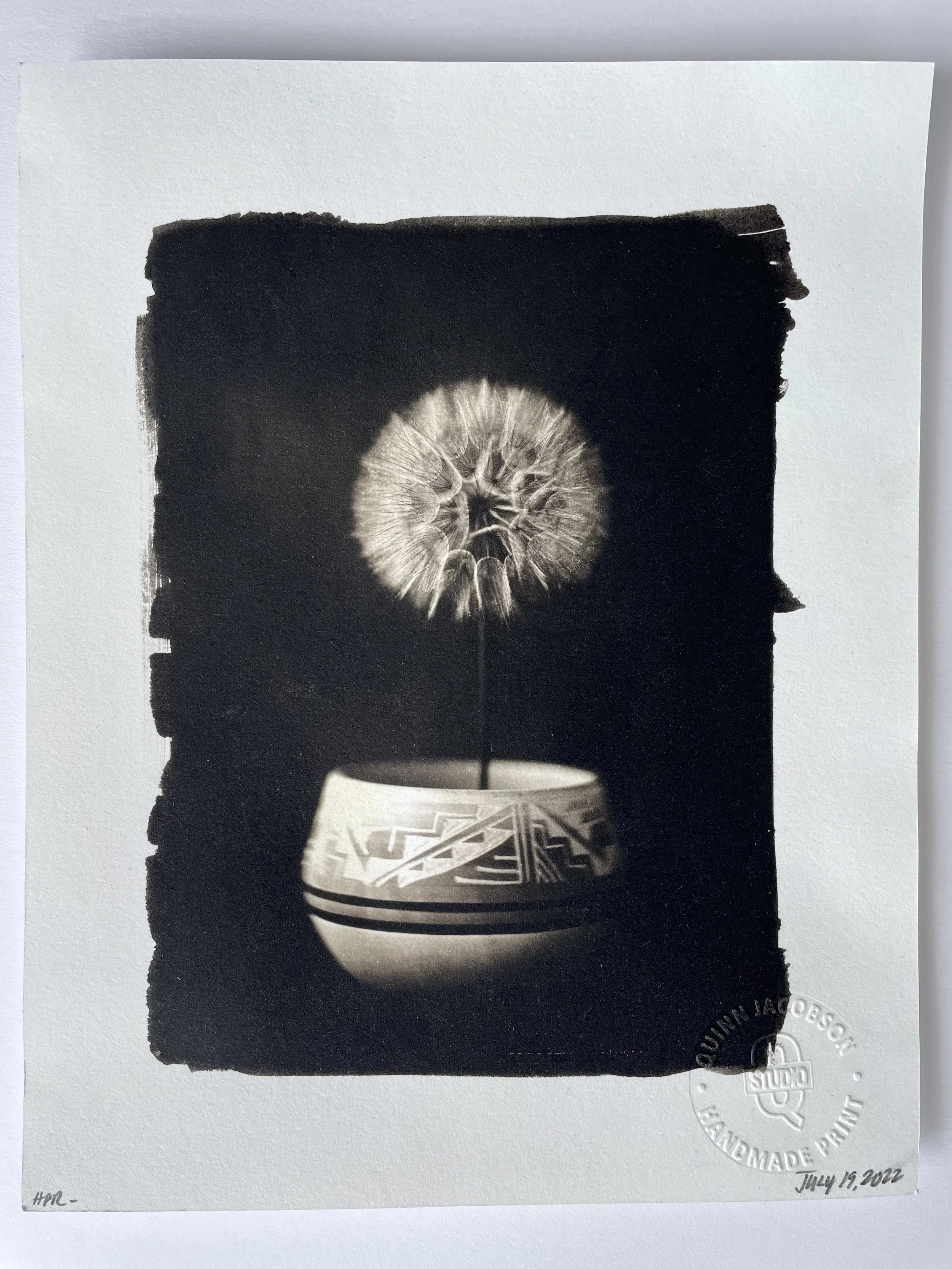

The Yarrow plant gone to seed-a photogenic drawing.

A medicinal plant gone to seed—a print from the vellum negative on salted paper.