“What you’re trying to create is a certain kind of indispensable presence, where your position in the narrative is not contingent on whether somebody likes you, or somebody knows you, or somebody’s a friend, or somebody’s being generous to you.”- Kerry James Marshall, NPR News, 2017

THE BOOK

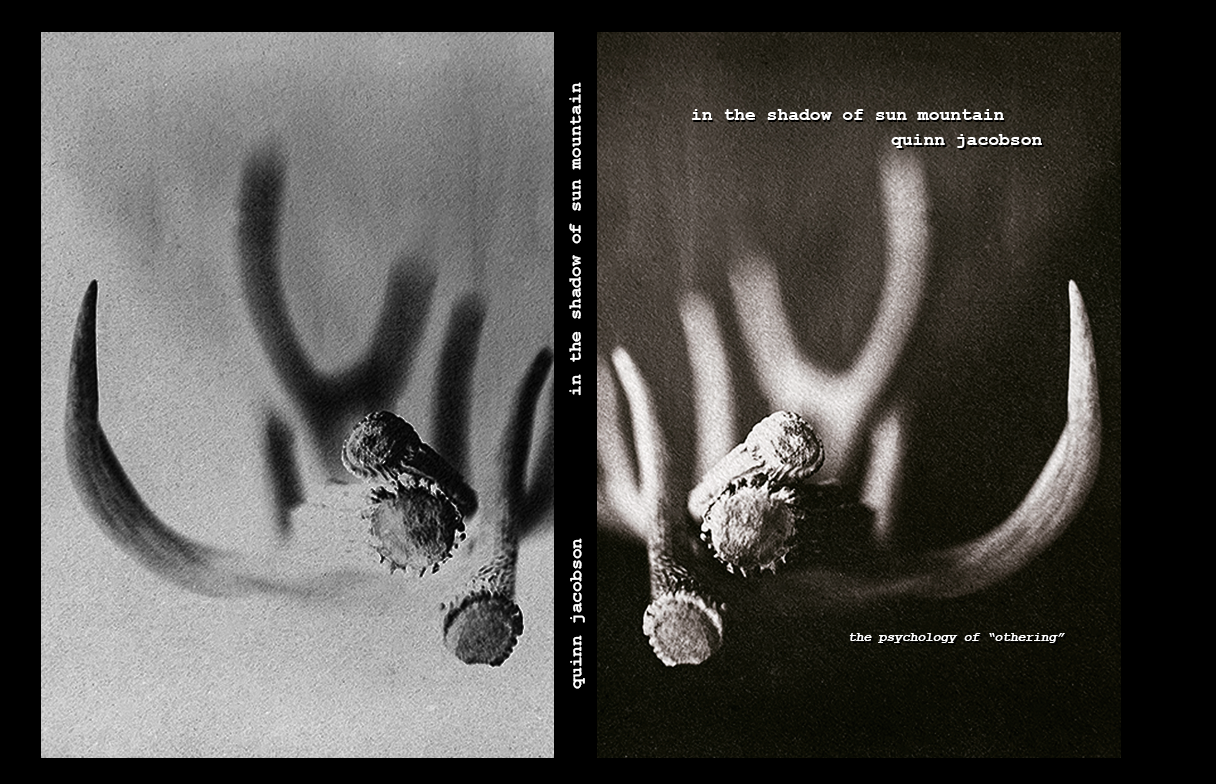

I’ve decided to publish a book on this work. The title and subtitle will read, "In the Shadow of Sun Mountain – The Psychology of "Othering." That’s probably not a surprise to a lot of you, but I wanted to share the news.

This will be one way of putting the work out there. There will be other projects to accomplish this as well. Since most people will never see the work in person (an exhibition), and since the book will have more images than an exhibition, this is the most efficient way to get these images and ideas to the masses or the few that are interested in it. And there will be a substantial amount of writing that I could never get to communicate in a gallery setting. If people take the time to read it, they will really understand what I’m trying to do with the work.

I’m not sure when this will be published. It will probably be at the end of 2023 or the beginning of 2024. It will be a hardcover and, so far, it looks to be about 200+ pages. Quite the tome for a “photobook.” It’s not really just a photobook, though. I want to transcend that a bit and give some in-depth reasoning, philosophy, and “behind-the-scenes” stories about the work. I’m leaning heavily on Becker and Solomon for this. It will be scholarly in that sense, for sure.

The book will concentrate on the history of "othering" but will also shed light on current events. Humans simply repeat history. The images are cradled in the lives of the Ute-Tabeguache of Colorado—my home. But the concept will go even beyond that. It will be broken down into four sections; the introduction and artist’s statement; landscapes, flora, and fauna; objects, and symbols. The book will have between 15 and 20 essays on various topics related to history, psychology, and my experience making the work. I’m repurposing some of the writing that I’ve published here. The essays will be edited and polished up a bit for the book.

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF “OTHERING”

I’ve always had a preoccupation with the psychology of "othering." I’ve been talking about it and asking questions about marginalized communities and our treatment of them for over two decades, maybe even longer. I’ve made several bodies of photographic work on this topic too.

Ever since I can remember, I’ve wondered why people group up and make everything "us and them." They will argue and fight about anything and everything. And I mean everything; sports teams, geography, professions, politics, Facebook groups, religion, gender, etcetera.

I’m guilty of it too. I feel the feelings and think the thoughts like everyone else. I suppose the difference is that I realize when I’m doing it and I’ve never taken it to extremes—at least I hope I haven’t.

I've always been aware of my thoughts about differences. I believe that’s where my questions originated. I’m always willing to have a rational and reasonable discussion about them, whether they’re real or perceived. I don’t think we can ever not have these feelings and thoughts; we’re built this way. It’s baked into our death anxiety condition—and it’s a powerful buffer we cling to for security and self-esteem.

That’s why Ernest Becker’s writing is so potent for me. He was able to answer questions that I’d been struggling with for 30 years or longer. He clearly laid out the human condition, and there’s not much room for argument. His theories are solid. Sheldon Solomon and his crew put his theories to the test—the literal test. And they panned out. Read “The Worm At The Core: The Role Of Death In Life” it will make you a believer. It is what it is, whether we like it or not, understand it or not, or agree with it or not. That’s where we are.

His books have had such an influence on me; it’s really pushed my (photographic) work in a different direction. I’m primarily a portrait photographer and artist. I would normally have people in front of my camera. Not anymore. Based on his theories of the denial of death, Becker gave me insight into making work that was both abstract and impactful, sitting together with these ideas. If you look through the work and study it, you’ll find what I’m talking about. For me, it’s Becker’s theories visualized.

The big problems come when people rationalize their "othering"—they justify it and not only make it okay, they think it’s their "duty to stand up for what’s right." I’m sure you’ve seen examples of this recently. I could list several just in the past week alone, everything from mass shootings to anti-mask people freaking out at school board meetings and many more.

It’s beyond worrisome at this point. When I feel emotional about it, I simply refer to Becker’s words. I understand why it’s happening, and that seems to calm me down. Knowledge is power. Plato said, "The true lover of knowledge naturally strives for truth and is not content with common opinion, but soars with undimmed and unwearied passion till he grasps the essential nature of things." That’s always been my goal, especially now.

My book will be a story of "othering." A specific story about the Ute/Tabeguache that once lived where I live now. It will be an artistic and psychological trip into the “why.” It will explain, as best I can translate, Becker and Solomon's reasons behind the genocide of Indigenous peoples. I see the pictures as the residue, if you will, or reminders of the past. For me, they hold both the beauty and the tragedy of the people and the place. I hope they will evoke emotions and feelings in the viewer. And I hope the written portion gives some answers or explanations about all of it, past and present.

At the end of the day, my goal is to add to the long list of people who have tried to shed light on human behavior, to make people aware of the unconscious, and to plead for change—real personal change. One of Becker’s hopes was that everyone understood his theories. Just the fact of knowing about this can help bring about change—one person at a time. I know this is too much to ask. It's not realistic. But I can still hope.

I’ll close this essay with some positive words. And maybe, in some abstract way, some answers to the mortality salience problem—the death anxiety problem.

Every day, I try my best to do the following: Be grateful for everything. Be happy to be alive. Be in awe of life—of living and of nature. And try to be humble. Not in a self-deprecating way, but in a modest, unpretentious, unassuming way. Share the good things that you have to offer the world. And find meaning and significance in the things you love to do.

These are big asks in our world of social media (siloed lives), our drive for wealth and fame, and our desire to “stand out” and compete with the world. I’ve heard Sheldon Solomon recommend pursuing noble attributes (previous paragraph). They may bring some relief to your existential crisis, and your death anxiety.

Mockup idea #2

Mockup idea #3:

I’m thrilled with this picture (a photogenic drawing of pigweed). When I saw it after I pulled the plant from the paper, I was beside myself. It reminds me of this song I recently heard. It’s called “Turtles All The Way Down,” by Sturgill Simpson. I listen to a wide variety of music; no genre is off-limits to me. As far as country music goes, normally I would go for the older stuff like Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Geoge Jones, Tammy Wynette, etc.

Lately, I’ve been listening to him (Sturgill Simpson), and I like a lot of his music. He’s a great storyteller. I couldn’t believe the lyrics when I first heard the song (“Turtles All The Way Down”). He talks about psychedelics and how they’ve changed him. And he comes down hard on organized religion. I’m familiar with the Bertrand Russell story of turtles all the way down and have read Stephen Hawking’s book, “A Brief History of Time,” where he tells that story as a rebuttal to the existence of God. It’s really about infinite regress. But I digress. I’ll write an essay about it. I think people might find it interesting. This image reminds me of these lyrics in the song:

“I've seen Jesus play with flames

In a lake of fire that I was standing in….

There's a gateway in our minds

That leads somewhere out there, far beyond this plane

Where reptile aliens made of light

Cut you open and pull out all your pain..,”