I connect with her thoughts and approach to making art. I consider my work about loss and beauty. While not as personal it's still a universal concept.

Painter Alyssa Monks finds beauty and inspiration in the unknown, the unpredictable, and even the awful. In a poetic, intimate talk, she describes the interaction of life, paint, and canvas through her development as an artist, and as a human.

A Whole Plate Cyanotype from a Wet Collodion negative.

Concept and Craft, Why Are They Important?

“In The End of Art Donald Kuspit argues that art is over because it has lost its aesthetic import. Art has been replaced by "postart," a term invented by Alan Kaprow, as a new visual category that elevates the banal over the enigmatic, the scatological over the sacred, cleverness over creativity. Tracing the demise of aesthetic experience to the works and theory of Marcel Duchamp and Barnett Newman, Kuspit argues that devaluation is inseparable from the entropic character of modern art, and that anti-aesthetic postmodern art is its final state. In contrast to modern art, which expressed the universal human unconscious, postmodern art degenerates into an expression of narrow ideological interests. In reaction to the emptiness and stagnancy of postart, Kuspit signals the aesthetic and human future that lies with the New Old Masters. A sweeping and incisive overview of the development of art throughout the twentieth century, The End of Art points the way to the future for the visual arts.” In the book, “The End of Art” by Donald Kuspit

On Friday, I posted about choosing your medium. I have another word for it. I call it “craft”. I use the word in the context of marrying CONCEPT and CRAFT. Allow me to try to explain what I mean.

Plate #104 - A Whole Plate bleached Cyanotype from a Wet Collodion negative.

The concept is WHAT the story or work is about, and the craft is HOW it is made, or what materials are used and why. If I’ve learned anything over the years making (art) pictures, it’s this: You must have a strong, coherent narrative. You must marry or join the craft or medium with the narrative. And you must have context and intention supporting all of it. Give context to what the work relates to, intention, why was it made, and explain why you chose the materials that you did. How is it all connected and how does it relate to you, the creator/maker/storyteller? In other words, what is it that you want the viewer to think about or understand after seeing the work? In one sentence, “My work is about ___________ (fill in the blank).

This is a heavy lift. It’s very difficult to do. That’s why few people do it. I always hear the counter-argument that art shouldn’t need any of this. That it should stand on its own, without explanation. In part, I understand this argument, however, I don’t agree with the premise. Most of the time, I hear this from people who have nothing to say about their work. I’ll write more about this in the future.

“Splitting Aspen” Plate #118 - A Whole Plate bleached and toned (tannic acid) Cyanotype from a Wet Collodion negative.

So few other mediums get away with that kind of argument. In the photography world, we get away with a lot. If you make a pretty picture or a “chocolate box” picture, you’ll get praised and plenty of accolades for it. You might even win an award! It doesn’t have to have any narrative, context, or intention, and it wouldn’t matter if it were a digital snap or an ultra-large format historic process image. If it’s based on technical merit, you’ll be in the same boat. It’s big, it’s this process or that process, etc. The technical folks will love it. If it’s pretty and “knowable” or a technical feat, the masses or the techies will like it. And if you’re making work that the masses or techies like, it might be that influence driving you (I make pictures that people like or that are technically difficult) rather than making pictures based on a personal, authentic narrative. I call these types of photographers, “commercial photographers” and “process photographers”. A lot of times, they call themselves artists.

That’s the superficial part of making photographs. Let’s talk about the other end of the spectrum. I just read Donald Kuspit’s book, “The End of Art” (see quote above). I don’t agree with all of it, but I certainly understand where his head is at when it comes to postmodern and post-post-modern art. He rails on Damien Hirst and other artists that work in such a conceptual way it seems ridiculous to a large part of the population. Their commentary on suburbia, and the mundane can be confusing if you don’t know the context of the work. A lot of it is ridiculous hyperbole. Made up to make money and draw attention.

It upsets me that the art world creates these kinds of environments. It doesn’t need to. It alienates so many people who would, otherwise, understand art and appreciate it. It would enrich their lives and could even make them better people. I’ve heard people say, “Oh, I don’t go to art galleries, I don’t understand art”. That statement always makes me sad. It’s the out-of-touch elitists that has put that in the mind of the average person. Every human being can understand art. It’s up to the artist to make that happen (the point of this post). Whether the people like the work or not is a different question. But they should be able to understand the intention behind the work.

A Whole Plate Cyanotype from a Calotype (Paper) negative.

I always ask people why filmmakers have to tell stories in their work - you know, beginning, middle, end? Character development, plot, etc. Or why do musicians have to follow certain rules to make music? You know, notes, scales, timing, etc. Why do writers have to use proper grammar and construct a sentence in a certain way? You know, subject, verb, noun. There are “rules” to follow in these mediums so that the audience can understand the story or the narrative. I’m not a “rule” follower per se, I think it can be really good and really creative to break rules, but not just for the sake of breaking them or the inability to construct a narrative.

Connecting ideas and concepts to life experiences is what art can do really well. It can draw people in, tell a story, and leave them questioning their beliefs, opinions, etc. Art can make the world a better place, or a more interesting place, but it needs to be understood in order to do that.

I’m not preaching about beating people over the head with didactics or statements. But there needs to be context and intention behind the work - and it needs to be accessible to the viewer. I’m simply stating that pretty pictures or chocolate box pictures won’t stick with you, or make you think very much. Art should provoke, it should make people question and think. You can accomplish that through authentic and connected narratives.

Think about what you have questions about. What are you concerned about? What are you most connected to? What do you love? What do you dislike? Like Socrates said, “examine yourself” and find out what your art is about. Then share those ideas with the world. There will be other human beings that connect with the work. They will find it important and meaningful. It may only be 10 people or it could be 10,000 people. It doesn’t matter. What matters is that it gave you meaning and significance.

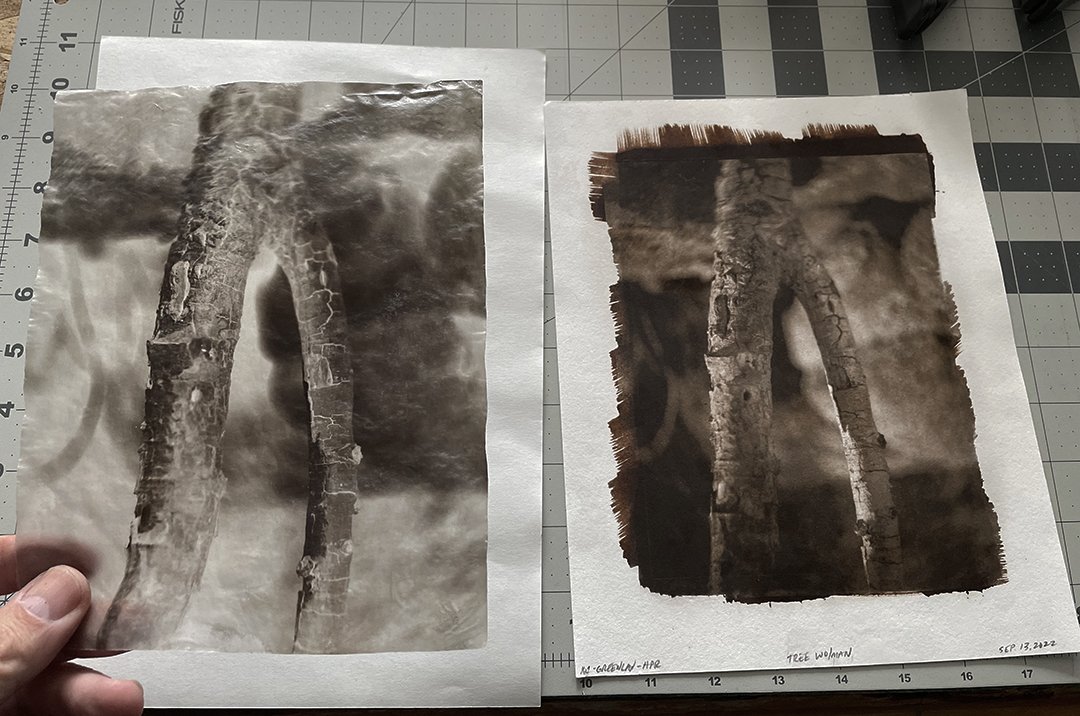

A Whole Plate Rawlins Oil Print from a (Greenlaw) Paper Negative. And yes, I printed it emulsion side up (away from the paper) to gain more softness in the print.

How Does The Medium You Choose Affect Your Work?

When we talk about “medium” in art we are referring to the materials and processes we use to create the work.

It’s important to select the appropriate medium for your work. It’s probably a bad analogy, but when the medium and the message are in conflict or don’t work well together, it’s kind of like going to a wedding dressed in your swimming attire. It just doesn’t fit.

Maybe that’s part of your narrative, and if it is, ignore this post. I’m addressing someone that’s putting together a story and that wants the visuals to support the narrative.

There are a lot of questions to ask when you start working on a project. Maybe the project is something that you’ve been thinking about for a long. Or maybe it’s something new. Either way, you need to find the medium that best suits the work.

For the majority of my writings here, I’m referring to the use of photography for making art. Not always, but most of the time. I’m going to use photography in this post so I can easily address the question about the medium affecting the work.

If you’ve started a project, or you’re thinking about one, how do you lay it out? Or, how do you organize your thoughts about it? What process do you go through? And when does the medium come to mind? How important of a role does it play in the work?

When I talk about the medium, I’m referring to format, type of film, optics, process, or processes, paper, presentation, etc. To me, that’s all very, very important. Since I work in 19th-century photographic processes, I want my narrative to be supported by the medium. I can’t stress how important this is to me. I want it to feel “right” and natural. My objective isn’t to confuse the viewer, or play tricks on them, but to engage them. It’s almost like having a dialogue. In order to do that, we need to speak the same language and have the concepts and ideas make sense. The medium is key here. For my project, “In the Shadow of Sun Mountain,” I’ve selected the most period-appropriate processes I can. My story takes place between 1850 - 1880. This is when the colonizers removed the Ute/Tabeguache from Colorado. Specifically removed them from where I live now.

For the past year, I’ve worked with wet and dry collodion negatives. Just recently, I started back making paper negatives (Calotypes) too. I’ve experimented with some very obscure negative-making processes in that time as well. I’ve made Platinum Palladium prints, Kallitypes, both modern and vintage, and Rawlins Oil prints.

These processes fall within the time period I’m referencing. I’m using the Whole Plate format. It was popular during this period as well. And for optics, my glass ranges from 1858 - 1877. Everything fits. I want the images to appear as they would have during this time.

The next thing I’m addressing is the aesthetic. I want the images to create a feeling of memory. A feeling of the past, like a half-remembered dream, if you will. It’s important for me to address both the tragedy of what happened to the Tabeguache as well as show the beauty of their land, plants and symbolic objects through these images.

The medium carries a lot of weight in art. How and why it was made is central to the story being told. Think about how you address the impact of the medium. If it’s an afterthought, I would reconsider the question.

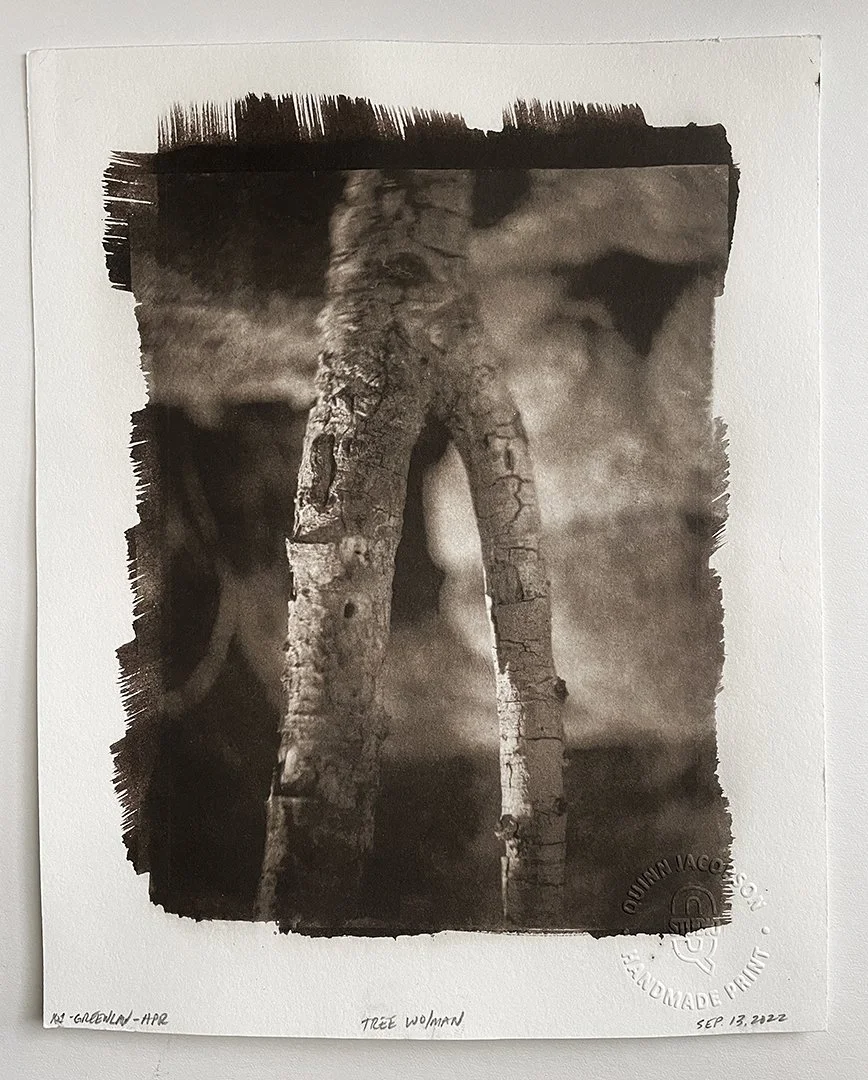

The Aspen Tree Wo/Man. Whole Plate toned Kallitype (K1) from a Paper Negative (Greenlaw).

It's amazing to behold the continuous quivering of aspen leaves in groves even when there is no apparent breeze.

According to Ute legend, the reason for this unique aspect of the aspen tree happened during a visit to Earth from the Great Spirit during a special full moon. All of nature anticipated the Spirit's arrival and trembled to pay homage. All except the proud and beautiful aspen. The aspens stood still, refusing to pay proper respect. The Great Spirit was furious and decreed that, from that time on, the aspen leaves would tremble whenever anyone looked upon them.

Out West Magazine, July 1873

What Does It Mean To Be Creative?

I’ve asked this question a lot in my life. You hear the words “creative” and “creative energy”, “art”, and “artist”, in the photography world quite often. But what do they really mean?

I’ve talked about making “original” work before. Some of you pushed back and said that nothing is original, it’s all been done in the art world. On one hand, I would agree. On the other, I disagree.

When I use the word, “original”, what I mean is that YOU are original, the maker or creator of the work. There’s only one of YOU! That, in and of itself, starts the process of making original work. The next part is authenticity. Being true to the importance you feel about the work. Nothing derivative (copied) and nothing trendy or popular can be original or creative.

Following your vision, whether people like it or not is very important. If people don’t understand or “get it” it doesn’t matter. Creating art is something a person is driven to do. It’s almost like you can’t help it - it’s compulsive, or compelling in a way. It comes from a place that has nothing to do with money, fame, social media, etc. It has to do with the need to express. To get what’s “inside” out and in the physical world. It’s manifesting deep feelings, emotions, questions, concerns, etc. Making the intangible, tangible.

If you feel this need, or you’re compelled to create, you know exactly what I mean. You’re somewhat preoccupied with ideas, thoughts, questions, etc. about the work you want to make. It can take the form of a technical issue or problem to serve the conceptual questions or vice versa. We address these as problems in making art because that’s what they are. It’s not stated in a pejorative way, or bad way, everything in life is a problem to be solved, and creating art is no exception.

I’ve tried to work through a lot of these questions over the years by making photographs. Each year, I get a little wiser and understand myself better. You don’t have to be middle-aged to get it, but the years of experience never hurts. I think the best piece of advice that I ever got in reference to being creative was, to be honest, and true to your vision. As I said before, don’t follow trends, don’t make what’s popular, make what’s yours!

Life asked Death, “Why do people love me and hate you?” Death replied, “Because you are a beautiful lie and I’m a painful truth”.

The Quaking Aspen & Granite Rock. Whole Plate toned Kallitype (K1) from a Paper Negative (Greenlaw).

Understanding Art (Immortality Projects) and Death Anxiety

The psychoanalyst and philosopher, Otto Rank said, ”Art is life's dream interpretation.”

Rank was fully aware that art acted as an “immortality project” for humans. In other words, we all have projects that we want to live on beyond our physical selves (after our death).

“The Great Mullein” - Kallitype print from a paper negative.

We need these. What are they? They may be things like having children, getting a big job, wearing the latest fashions, and all kinds of material things. It could be owning a collection of antiques, belonging to a church, or a political group, getting an advanced degree, etc. These projects can be anything that allows us to be a part of something that transcends our death. It’s a way for us to “achieve immortality”.

We’re not afraid of actually dying. We’re afraid of being forgotten. That’s the crux of the issue. If you feel like you’re going to be forgotten, your life becomes meaningless and insignificant. We can’t bear that, psychologically speaking. So we need to create these illusions in our lives - “immortality projects”.

Think about the billions (some estimates say 10+ billion) of people that have lived and died on the earth. The vast majority, 99.99999%, are forgotten. Only a few in recent history, mostly bad or infamous people, are remembered. And, over time, they will be forgotten, too. It’s a frightening thought for most people.

Thinking that your life has no significance or meaning and that you’re going to die and decay is unbearable. Becker refers to us as “food for worms”. As humans, we all engage in activities that allow us, for a time, to disengage from the fear of dying and being forgotten or death anxiety. They provide us with what Becker calls self-esteem. Self-esteem gives us meaning and significance in the world. Without it, we can’t function, or, we can’t function very well. There are a lot of people that suffer from no self-esteem - you see them everywhere - low functioning, problematic lives. We need to feel good about our lives. And we do that through our projects.

One of my “immortality projects” happens to be art. I have a few in my life, but that’s the one you’d be familiar with. Am I aware of why I’m doing this? Yes, I am. Am I aware that in the “big picture” it’s meaningless? Yes, I am. Why do I keep doing it? Because I want to feel meaningful and significant while I’m here and want something of “me” to live on beyond my physical death. That’s why. And I’m fully aware of all it implies. I’m very aware that my art is meaningless in this context. Everything is. We can’t live every day with that terrible fact. We need a coping mechanism, a good and positive one. We need these projects, whatever they are, to survive and thrive in this life.

Becker was clear that this is not an ego thing. This is completely normal and even rational in some contexts. If we allow ourselves to fall into constant fear and anxiety about the meaninglessness of everything, we suffer and the people around us suffer as well. Most people are not consciously aware that this is going on in their lives. They only think that the new job is going to provide success or the new relationship is going to bring happiness. And they probably will. It will be in the context of fending off death anxiety. I’ve said it a lot, all human activity is driven by death anxiety, or in the service of keeping it at bay.

Dr. Sheldon Solomon is writing and talking a lot nowadays about another way to deal with death anxiety. He says that gratitude and humility will suffice, or can replace immortality projects. Or living in gratitude and humility can even become an immortality project itself. I’ve been thinking a lot about his ideas. I can see what he’s referring to in general. Both of those attributes are the polar opposites of death anxiety responses. The fear and worry are subdued with gratitude and humility.

So if you’re aware of this, pick projects that are positive. Projects that won’t hurt other people; and projects that will help humanity in some way; large or small. Express whatever it is that you feel connected to and concerned about. But be aware that we are all vulnerable to harming “the other” - people who are different from us, people who look different, believe different things, etc. Be conscious not to engage in projects that are harmful and negative.

"There was just that moment and now there's this moment and in between there is nothing. Photography, in a way, is the negation of chronology."

-Geoff Dyer, "The Ongoing Moment"

A toned Kallitype (Nicol’s) process) from a Whole Plate paper negative (Greenlaw) of a reconstructed Ute Lodge or Wickiup - Rocky Mountains, Colorado.

The Ute Lodge or Wickiup

THE UTE LODGE or WICKIUP

In the mountain forests of western Colorado, archaeologists and tribal members have recorded scores of sites that contain the remains of hundreds of wickiups, cone-shaped wooden structures built by the Ute, or Nuche, people more than a century ago.

Archaeologists have found and documented at least 366 wooden features at 58 sites so far, along with other structures including tree platforms, ramada-like shade shelters, and brush fences, according to national forest officials.

“Wickiups and other aboriginal wooden features, such as tree platforms and brush fences, were once commonplace in Colorado,” said Brian Ferebee, deputy regional forester for the U.S. Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Region, in a press statement.

“Few examples are still in existence; the majority of the remaining features can be associated with Ute culture and consequently represent the only surviving architecture of the state’s living indigenous peoples.”

(Blake De Pastino from Western Digs)

Whole Plate paper negative (Greenlaw) of a reconstructed Ute Lodge or Wickiup - Rocky Mountains, Colorado.

The paper negative inverted in Photoshop. It was made with a vintage Derogy lens - wide open f/4 for 3:30.

“The Struggle” - a toned Kallitype (Nicol’s process) from a Whole Plate paper negative (Greenlaw) on Clearprint paper.

The Weight of the World

We all have things that weigh us down. Things that feel heavy on our hearts and heads. Sometimes they’re very personal. Family, relationships, finances, jobs, and life, in general, can be difficult to navigate at times. Some of the things that weigh on us are more general, or “big picture”. The big world events, historical events, political events, and third-world countries with terrible problems can be things that we feel helpless to change.

I struggle with the latter quite a bit. The “big picture” problems. I see the world, and this country specifically, repeating history. I see things that are very disturbing. Americans are very divided today and are looking for scapegoats.

When we, as people, look for “the other” to blame our problems on, things get bad. I see a lot of this going on today. That’s what my project is about; how death anxiety creates situations for humans to commit terrible acts. The knowledge that we are going to die motivates all of our activities, good and bad.

For me, art has always been a way to confront, address, or deal with issues that concern me. So when you struggle with problems, you can create something that addresses those concerns and maybe find some catharsis, or relief through making the art or even in the act (physical) of making it.

In fact, the physical act of making art does that for me. The content, ideas, or concepts are, of course, very important too. The final image or piece is what I consider the residue or evidence of this process. One of the reasons I work in these old, arduous photographic processes is to fulfill that physical need in creating art.

Technology is great. We all depend on it and it can be positive in a lot of ways. However, when it comes to art, it doesn’t work for me. I can’t sit at a computer and generate images and press a button to print them. It’s empty, mechanical, too perfect, too impersonal, there’s nothing physical and there’s nothing that connects me to the work.

I know there are people that really enjoy the digital stuff, computers, printers, etc., and feel satisfied making work that way. I just don’t connect. The old processes and the physical act of creating are where I find catharsis, relief, and some satisfaction that what I’m doing matters and has significance in the world.

“The Struggle” - a Whole Plate paper negative (Greenlaw) on Clearprint paper.

The Great Mullein - East Morning Light - Plate #115 - Whole Plate Palladiotype from a wet collodion negative.

Verbascum thapsus

THE GREAT MULLEIN

Native Americans utilized it for ceremonial and other purposes, as an aid in teething, rheumatism, cuts, and pain. It's also used for a variety of traditional herbal and medicinal purposes for coughs and other respiratory ailments.

The Great Mullein - Plate #116 - Whole Plate Palladiotype from a wet collodion negative.

The Great Mullein plant with the east morning light - September 5, 2022. Whole Plate wet collodion negative. This is inverted - not printed. Will print these tomorrow.

Humans Need to Create Illusions

Ernest Becker wrote about the “human animal” needing to create illusions in order to deal with the knowledge of our impending death. What does that mean? It means that out of all the life on this planet, humans are the only creatures that KNOW we’re going to die. That creates a huge psychological burden to bear.

Because we have this “memento mori” knowledge and it forces us to create what Becker calls “culture”. That’s the illusion of meaning and significance. We feed off of our “culture”. It’s external, not internal. We use it for our self-esteem. Self-esteem is a state of feeling like our lives have meaning and that we have significance. We’re both in awe of life and terrified of it as well.

If you deep dive, you can figure this out. I know these theories are difficult to wrap your head around, but they are incredibly powerful when you do.

Everything around us has been created as a type of distraction or illusion to keep our death anxiety at bay. All human activity is driven by death anxiety. Or, a better way to say it is, that all human activity is in service of keeping our death anxiety at bay. We all participate, no one is without this burden.

Without these illusions, we would be curled up in the corner, unable to function. Completely paralyzed from facing the reality of our existence. It is terrifying. To think that we are simply frail, weak animals that will decay, die, and be forgotten seems unbearable. Arthur Rimbaud said, “The only unbearable thing is that nothing is unbearable.” I think he was fully aware of our human condition.

The Great Mullein plant with the east morning light - September 5, 2022. Whole Plate wet collodion negative.

The Great Mullein plant going into flower - September 5, 2022. Whole Plate wet collodion negative. This is inverted - not printed. Will print these tomorrow.

The Great Mullein plant going into flower - September 5, 2022. Whole Plate wet collodion negative.

Calotype (paper negative) - Three Aspens - inverted.

Calotype (paper negative) - Three Aspens - inverted. I used Crob ‘Art paper to make this negative, I may try to print it on the same paper.

Whole Plate print (toned Kallitype) from a paper negative (Calotype). The Great Mullein - September 3, 2022.

Calotypes (Paper Negatives) & Kallitype Prints

This is something that you don’t see every day in the photography world (historic photographic processes). A calotype (paper negative) and a kallitype (an old-school printing process). Both mean “beautiful” in Greek - “kalli” or “calo”.

The paper negative, invented by Fox Talbot (1800-1877), was patented in February 1841. Talbot called it, the “Calotype” of “Beautiful Type”. It was the first negative/positive process invented, Sir John Herschel coined the term, “photography” - “photo” (light) and “graphy” (writing). "Writing with light”.

It’s no secret that I have a passion for photography. The historic processes are so interesting to me and the history of photography in general. I’ve worked in almost every process from 1839 - 1980. My greatest interest is in the negative/print processes. There is nothing like a beautiful negative printed well.

As I work on my project (“In the Shadow of Sun Mountain”), I try to stay open to new ideas. Both technically and conceptually.

Over the past couple of months, I’ve been collaborating with Tim Layton of Tim Layton Fine Art. We’ve been working through some old printing processes from the late 19th century together. We were reviewing some information in a book called, “Coming Into Focus” by John Barnier and Tim was asking about the Calotype recipes and methodologies in the book. One thing led to another and I found myself making some Calotypes over the past few days. It’s been a lot of fun.

I first made Calotypes when I lived in Europe (2008-2009). I had an interest in exploring the pictorial look and feel but ended up using wet collodion for my work there. They are a lot of work, but what isn’t that’s worth anything today? I can see the possibility of adding to the project with some Calotype/Kallitype work. Like I said, I try to stay open to everything as it applies to creating a body of work. The danger is running down too many rabbit holes and never making the work. I know people who have spent decades perfecting a photo process and they have nothing to say with it - it’s heartbreaking and sad to see that happen. Don’t become a “process photographer” be an artist, create, express, think, connect, and tell stories. That’s our purpose.

The negative (Calotype) and print (Kallitype). The Great Mullein - September 3, 2022.