I’ve gone through a couple of iterations of printing. I have several prints that would not accommodate my mats. So I purchased this “tree of life” journal. It’s leather and has acid-free paper. I started “tipping in” my prints. I’ll use it as a journal for the work too.

The Studio Q Show: Saturday June 11, 2022

Join me next Saturday, June 11, 2022, at 1000 MST for the Studio Q Show. I’ll be talking about what I’m doing and clarifying some of the blog posts I’ve made over the past few months. It will be great to catch up with everyone and share the information. As most of you know, I’m working on, and refining, my new project that I’m calling, “In the Shadow of Sun Mountain (Tava-Kaavh)” - landscape and still life work that reflects the Ute (Nuuchui) tribe that once occupied this land.

I’ll show you some prints and negatives and talk about my approach to the work and my goals for it. It should be an interesting conversation if you’re into that kind of stuff, learning about and making art.

Bring your questions, comments, concerns, whatever. I’m happy to address them.

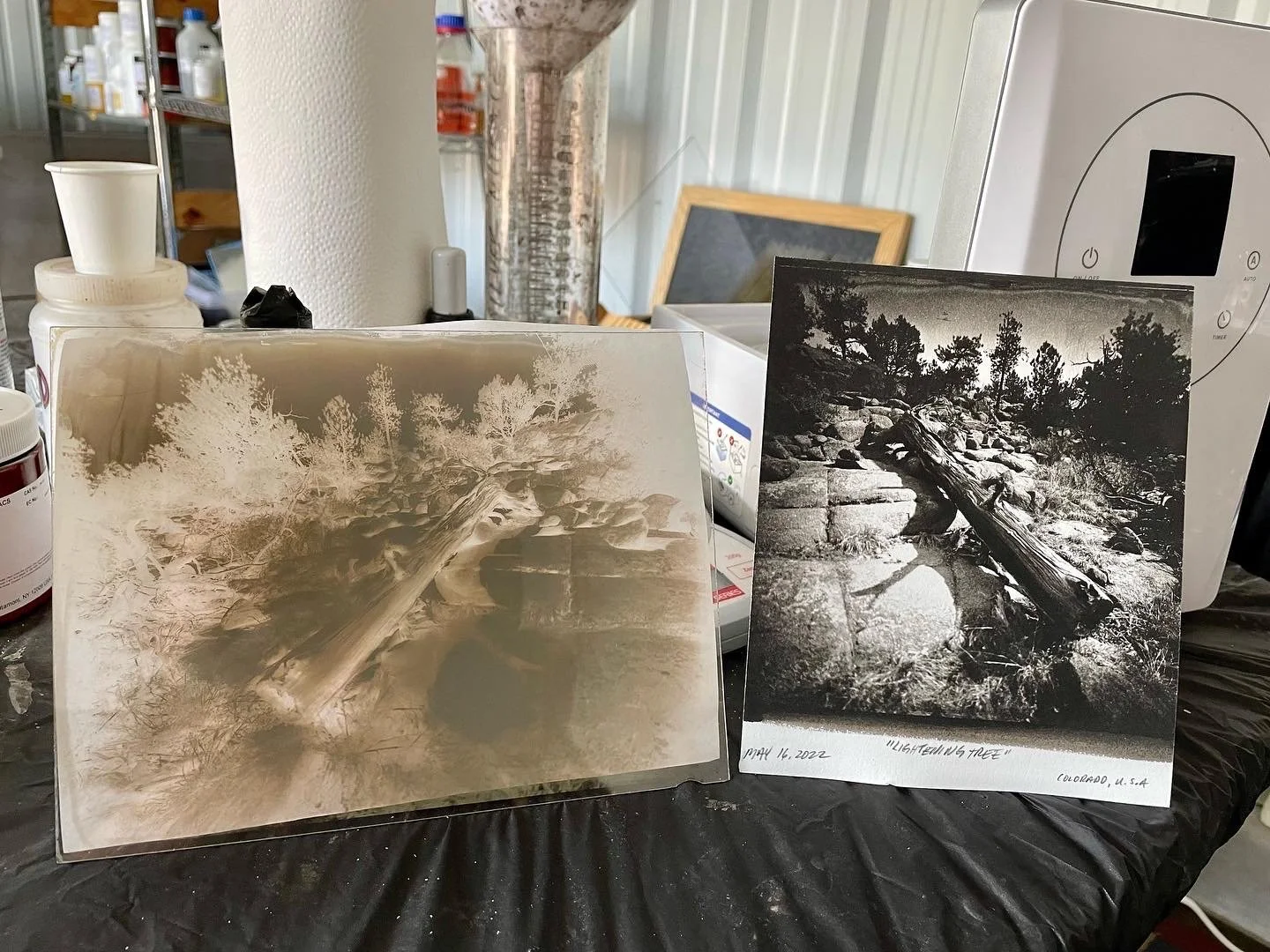

This is printed in Revere Platinum paper. I like this paper a lot - I use this and Hahnemühle Platinum for this work. The print is still wet here - the glare comes from the water.

Stone Water Dish - 9,000 Feet Above Sea Level

I’ve been wanting to make this image for several months. I’ve hiked to it five or six times. It’s a climb to get it and I wasn’t sure I could get my tripod set up or even get to it with all of my gear. It was not an easy photograph to make.

It sits about 9,000 (2.745m) feet above sea level. When Jeanne and I hiked up there today, there was a Rocky Mountain Chipmunk sitting in the dish. I wished I could have captured that, but we just enjoyed it before getting closer to make the image.

This is on our property. There are also CMTs (Culturally Modified Trees) here too. This “Stone Water Dish” was so unique that I had to get a plate made of it. Every time I hiked to it, I wondered if it would still be there.

The light was beautiful this morning. We got up to the “dish” at about 9:20 AM and there were some wispy clouds covering the sun. I used a collodion dry plate, of course, and made a 2:30 exposure. I processed the negative for about 8 minutes and made this Platinum Palladium print with my Ryonet at 5:30.

It’s Plate #7 of my project, “In the Shadow of Sun Mountain” (Tava-Kaavh). Take a really close look and see what’s happening in this image. It’s an entire story.

Dry collodion negative - Plate #7 - “In the Shadow of Sun Mountain”.

My iPhone rendering of the scene. Nothing like my collodion dry plate - the magic of 19th century photography!!

Looking At Photographs

A test print for exposure and chemistry. Every image I make takes one print (at least) to determine the exposure time and amount and type of chemistry,

Gregory Crewdson said, "Every artist has a central story to tell, and the difficulty, the impossible task, is trying to present that story in pictures."

It’s always an interesting conversation when the topic of looking at photographs comes up. When I say “looking at” I really mean critiquing, analyzing, thinking about, and evaluating. Criticizing is not a bad word, in fact, it’s very beneficial if done correctly. However, it’s a much more complex process than it seems. There’s some deconstruction as well as an understanding of the context and the intention behind the image.

Morris Weitz identified major categories of criticizing in his study of Hamlet. He defined it as describing, interpreting, evaluating, and theorizing. Can you look at a photograph and not think about it in this way? Yes, of course, you can. However, you’ll miss a lot and maybe even miss the meaning and substance of the work - the good stuff. It’s like looking at a cover of a book and not reading it, or only reading the title. You’d miss a lot. The goal is to increase appreciation and understanding of the work.

THE NARRATIVE OR STORY

Without a foundation of some kind, nothing can stand. A body of work (photographs) or a single image need a foundation too. We call this a narrative or story. Without it, it’s very difficult for the viewer to connect to your work in any meaningful way. Yes, they can project their own memories and experiences onto an image, or set of images, and dream up anything they want in order to connect that way, but it should be your story, not theirs. It’s your work.

Maybe that’s not important to you. Maybe it’s enough for the viewer to like the technical aspects of the process you used or the content of the photograph; trivial stuff, weird stuff, cool stuff, bizarre stuff, nudity, etc. Maybe you feel it’s good enough that there’s an emotional response by simply looking at the image without having any information about it. It’s possible that you don’t even care if you have a story or not (most don’t). I can understand all of these positions. I get it. The question still remains, is this the best way or most productive way to make work or have someone view the work? I suppose it depends on your objective. Selling images, or commercial work, and expressing ideas, also known as fine art, are mutually exclusive. In other words; they’re water and oil. Rarely can you have both, but it does happen for a few. Artists like Sally Mann, Joel Peter-Witkin, Nan Goldin, etc. come to mind. For most of us, it’s one or the other. You either make pictures for someone else or you make pictures for yourself. I’ve been fortunate over the years to hit that magic scenario with a couple of exhibitions of my work. My time in Paris, France was very good. The work was all mine and it sold very well. But again, it’s rare. I choose to make my work as authentic and personal as I can. Regardless of selling it or not.

My goal has always been to share ideas, and information and make people think about my ideas, theories, and questions through my images. I want to tell a story about something I care about. William Klein said, “Be yourself. I much prefer seeing something, even if it’s clumsy, that doesn’t look like somebody else’s work.” Your work will be more “yours” approaching it in this way. Too much work is made in the style of emulation or imitation - it becomes derivative quickly.

RESPONSIBILITIES

Both the artist and the viewer have some responsibilities. They’re very different responsibilities, but they do have them. The artist has the responsibility of providing the viewer with an authentic narrative. The story, as abstract as it may be, or not, should give the viewer a chance to understand the context and intention of the artist. What is this work? And why was it made?

The viewer should approach the work looking for the narrative, or reason the work was made. It’s on them now, not the artist. I’m not saying that everything needs to be explained and justified. Not at all. There’s plenty of room for mystery and unresolved elements. And there should be. However, to even get to that point the aforementioned needs to happen.

CONCEPT & CRAFT

Irving Penn said, “A good photograph is one that communicates a fact, touches the heart, and leaves the viewer a changed person for having seen it. It is, in a word, effective.”

What do I mean by “concept and craft”? The concept is the story/narrative or reason the work was made - think context and intention. And the craft is how it was made - why the specific processes or materials were used and how they connect to and support the work.

The balance between concept and craft is important to make a successful body of work. When you’re involved in 19th-century photographic processes, the technical, or the processes, tend to lead. The process becomes more important that the concept. What I mean is that the fascination is usually on the technique, not the content of the image. Sometimes, the interest is pointed toward the minutiae; what optic was used or chemistry was used, or what lighting was used. Not even considering the really important ideas behind the image.

I believe that the process should support the work, not the other way around. Photographers today lean heavily on the technique. I understand that. It’s a way into a world where you’re virtually a blade of grass, just like the other 100,000+ artists and photographers out there. How do you distinguish yourself? How do you make yourself stand out? 19th-century processes tend to open doors and get viewers. Regardless of the content or the quality of the work. And without narrative. Social media has driven a lot of these trends. We tend to be superficial and shallow when it comes to evaluating and considering artwork of any kind.

AUTHENTIC NARRATIVE: A RARE THING NOWADAYS

What is an “authentic narrative”? That depends on who you ask. In my opinion, it would be defined as an artist that has used the Socratic method (so to speak) to examine what’s most important to express about a question, a concern, a love, a dislike, beauty, ugliness, politics, social issues, etc. that they have. This is something that will keep the artist creating until the work reflects a part of them in a true and authentic way. I don’t think art should really answer any questions, I’m not sure it even can. The power in art comes from asking questions. The narrative should reflect that. It has to be deeply connected to the artist.

Over the past 20 years, I’ve seen the wet collodion world go from a small group of dedicated artists to a large group of people looking for their 15 minutes of fame. I’m not saying that’s wrong, I’m simply stating facts. Not everyone shares the vision of making meaningful, personal work. True, authentic pursuits of telling a story are rare now. When I got involved in these processes, they were used as tools to tell stories in a unique and new way, a personalized way. Not so much anymore. There are a few people still working hard to be authentic and using these processes as tools, not as “made you look” gimmicks to get their photographs published, shown, or sold. They’re rare and few and far between. And don’t misunderstand me, there is absolutely nothing wrong with making commercial work in any process or medium. Making money is fine. The issue I have is when commercial work is called fine art. Again, commercial work is making work for someone else - usually for money. Fine art is making personal work about something that you are interested in or care about and are asking questions about. Usually, you are connected to it in a real way.

If this is a topic that interests you, check out this video I made a couple of years ago: Showing Your Work and Criticizing Photography: Three Things - it will give you more insight into my theories and ideas about making art.

“Of course, there will always be those who look only at technique, who ask ‘how’, while others of a more curious nature will ask ‘why’. Personally, I have always preferred inspiration to information.” — Man Ray

Test print on Plate #7 - dry collodion negative/Platinum Palladium print.

Process Information: Making Prints and Organizing Negatives

I told you I would share my approach to the visuals and how I’m resolving the aesthetic that I want for this work. In other words, how am I printing and presenting the work?

First, let’s talk about the negatives. I’m making both wet and dry collodion negatives. To me, they are pretty much the same other than exposure time for prints. I find that sometimes, the dry collodion negatives require twice the light/time compared to the wet collodion negatives.

I’m using 1/2” (1.27cm) rubylith tape on the edges of my negatives. I’m doing this for two reasons. First, I want a “clean” look. And secondly, the 6.5” x 8.5” matboard opening will give that same dimension around the print. When I start mounting these, I’ll show you what I mean. You can get the idea from the images I’ve posted here with the images in the matboards. It creates a “depth” for viewing and “breathing” space for the photograph.

I’m trying to make two prints per day that are completely archival and printed to the perfect specifications that I want. There is a certain color, texture, and value I want for every print. Out of the 40 negatives so far, I’ve selected six for the final cut. That may change as time goes on, but for now, they are in the final. I can explain more about that as I include context for the images.

With my Ryonet UV printer, I can document each negative, chemistry, and exposure time and get a great copy of the print. I can’t do that with the sun. It’s too varied and I would waste paper and chemistry. I plan to do five (5) prints of each image. One for a book I’m doing - tipped in Platinum Palladium prints - more on that later, and four sets of exhibition and sale prints. I may offer up to send to Europe for shows and maybe the east coast here in America. In other words, this project will be “editioned” - only five prints of each (final) negative will exist.

I’m working every day on this project and I feel like I’ve got traction now. I feel it coming together. A big part of my methodology involves resolving the technical portion as well as the presentation or the visuals of the work. That helps me make photographs that are congruent and “inline” with the narrative. A technical and visual roadmap if you will. When I’m not making photographs or printing, I’m reading, writing, and researching. I'll share some of the text with you later. I’m not going to “title” these images. They are simply going to be called, “Plate #1, Plate #2, Plate #3”, etcetera. There will be a small paragraph of text with the plate number giving context to the photograph. As well as the technical information, i.e. Whole Plate Platinum Palladium print made from a wet/dry collodion negative. Etc. etc. etc.

In The Shadow of Tava-Kaavi/Sun Mountain

I’m almost 40 plates (wet and dry collodion negatives) into the project and have started my statement about the work. I wanted to share it to show those interested, how I evolve working on a project. For me, it’s important to spend time thinking and contemplating the process that will communicate the ideas and emotions in the photographs. This statement will change and grow as I make the photographs. This is a start, a rough draft if you will, but it gives me a direction and food for thought.

In The Shadow of Tava-Kaavi (pronounced Ta-vah-Kaavh) / Sun Mountain

At dawn, Tava-Kaavi is the first Colorado mountain to catch the sun’s rays. The mountain is over 14,000 (4.300m) feet above sea level. The Nuuchiu believe it’s where Mother Earth meets Father Sky.

The Tava-Kaavi or Sun Mountain is always present here. I call this body of work, “In the Shadow of Tava-Kaavi” because the photographs are all made literally with the great mountain watching over. Nothing escapes its presence. The Nuuchui (pronounced “New-chew”) knew that, too.

In these photographs, I’ve tried to show honor and respect to the Nuuchiu - the Ute people. Most of the work is somewhat abstract and can be interpreted in different ways, but all of the work was made with the Nuuchiu in mind. The places they hunted, the places they sheltered, and the places they practiced their spiritual and cultural way of life.

I consider this land as their land. In my mind, nothing has changed in that way. They honored it and respected it, never taking more than they needed. It’s a beautiful place. In a lot of ways, it’s “other-worldly”. The fauna and the flora represent all that the Nuuchiu loved. Their life here was balanced and good. As I spend time on the land and wander over the rocks and through the trees, I can feel that balance, that good life.

The Nuuchiu/Utes are the longest continuous Indigenous inhabitants of what is now Colorado. According to their oral history, they have no migration story - they’ve always been here. They were placed within their homelands, on different mountain peaks, to remain close to their Creator. Nuuchiu ancestors, in order to maintain transmission of cultural knowledge, taught generations through oral history about the narratives and the names ascribed to geophysical places and geological formations within their aboriginal and ancestral territory.

Plate #1: Whole Plate Platinum Palladium print from a wet collodion negative.

Plate #2: Whole Plate Platinum Palladium print from a wet collodion negative.

Whole Plate wet collodion negative - May 28, 2022 - Nuuchiu Project, Colorado U.S.A.

The Circle of Life and the Nuuchiu

Since our big snowstorm hit last week, I’ve had some time to do some research and reading. I’m trying to consume everything I can about the Nuuchiu (“New-chew” means “Mountain People”) also known as the Ute that lived here. The past few days I’ve been reading about their “Circle of Life” belief. I’m very interested in both their cultural and spiritual beliefs. I would like that knowledge to inform my images and support the work.

They’re the only tribe in North America that doesn’t have a migration story. That means they’ve been here (in Colorado) for time immemorial, or “forever”. I struggle with the idea of this land being stolen from them (their land) and moved to reservations. I hope this project will elevate and honor them in some way, that’s my desire. I remember a George Carlin quote. He said, “Sometimes people say, 'Do I try to make audiences think? ' I say: 'No no no,' because that really would be the kiss of death, but what I want them to know is that I'm thinking." That really sums up what I want for my work. Even if people don’t like it, I want them to know that I think about these things - a lot.

For now, I’ve decided to call my project, “Nuuchiu” or “Mountain People”. Although it won’t have images of the people, it will contain a lot of what was most important to them. Their land, rock formations, sacred sites, trees, and plants. I’m interested in the symbology of these things. In other words, they are literal but I want to show them symbolically as well. Tying stories to the objects is the most important thing to me. Telling their stories as best I can with my own interpretation of the objects. I’m in no way claiming expertise on Native American culture or history. I’m an artist asking questions, that’s all. However, I do live here and I can feel what they saw, how they lived, and the beauty and mystery they found here for thousands of years.

The Circle of Life is a central theme of Nuuchui/The Mountain People. The Ute people have a unique relationship with the land, plants, and all living things. The Circle of Life represents the unique relationship in its shape, colors, and reference to the number four, which represents ideas and qualities for the existence of life.

The People of the early Ute Tribes lived a life in harmony with nature, each other, and all of life. The Circle of Life symbolizes all aspects of life. The Circle represents the Cycle of Life from birth to death of People, animals, all creatures, and plants. The early Ute People understood this cycle. They saw its reflection in all things. This brought them great wisdom and comfort. The Eagle is the spiritual guide of the People and of all things. Traditionally, the Eagle appears in the middle of the Circle.

The Circle is divided into four sections. In the Circle of Life, each section represents a season: spring is red, summer is yellow, fall is white, and winter is black. The Circle of Life joins together the seasonal cycles and the life cycles. Spring represents Infancy, a time of birth, of newness-the time of “Spring Moon, Bear Goes Out.” Summer is Youth. This is a time of curiosity, dancing, and singing. Fall represents Adulthood, the time of manhood and womanhood. This is the time of harvesting and of change - “When Trees Turn Yellow” and “Falling Leaf Time.” Winter begins for gaining wisdom and knowledge - of “Cold Weather Here.” Winter represents Old Age; a time to prepare for passing into the spirit world.

The “Circle of Life” - from a whole plate wet collodion negative - May 28, 2022 - Nuuchiu land, Colorado.

Whole Plate wet collodion negative - May 28, 2022 - Nuuchiu land, Colorado U.S.A.

Culturally Modified Trees. I’ll talk more about CMTs as my project evolves, but you can read about them here, a post I did almost a year ago talking about my project. From a wet collodion negative - May 28, 2022.

Dallmeyer Lens & Platinum Palladium Print

Vintage lenses versus modern lenses. What’s best? I vacillate all of the time on this topic. On most days if you asked me, I would say that I’m a “vintage” guy. Other times, I would say that I like what modern lenses offer. In the end, it’s all about what you want to achieve. Both offer advantages and disadvantages. There is something about the vintage lens “look and feel” that appeals to me a lot. It’s a visual feast when you nail the exposure and allow the optics to sing. Truly wonderful. The modern lenses kind of lack that “je ne sais quoi”. Maybe because they are coated (which can be a plus in certain situations) or maybe because they are too perfect. I’m not sure.

Today, I’m a vintage guy for sure. There was such beautiful light here today. We have a snow storm coming in and it clouded up but was still bright. I love the rocks and trees on our property. I said this before, but I could make an entire body of work and never leave my land. And I just might do that.

I broke out the Dallmeyer 3B, stopped it down to f/5.6, and exposed a Whole Plate negative for 3 seconds. I chose wet collodion because there was some wind kicking up and wanted a tack sharp image. The dry plate would have been at least 8 minutes today. I couldn’t make that happen with the wind. I love the wet process, it does offer much better exposure times, no doubt. And, you can work in light that wouldn’t be optional for the dry process.

A Platinum Palladium print from a wet collodion negative.

A detail (iPhone snap) of the print. It doesn’t do it justice, but you can get the idea.

Questions About Collodion Dry Plate Negatives

I’ve had some questions and interest lately in my collodion dry plate negatives. If you have my book, “Chemical Pictures - 2020” you’ll see on pages 136-139 the collodion dry plate process. I give the basic outline of what I use in the “modern” version of the process. I have modified Russell’s original process a little bit from reading Thomas Sutton and James Mudd over the last years. Just like all of these processes, you have to find your own way - practice, experiment, practice some more, experiment some more. You’ll get it.

“Mohawk Rocks” Early morning light on the mountain. I tried to frame it with the tree branches. I really like the limbs crawling into the top of the frame. This is very “soft” light and changes the quailty of the print a lot. It was a 10-minute exposure at f/8 - 90mm lens. Platinum Palladium print - Whole Plate. May 19, 2022

Major Russell first introduced the collodion dry plate process in 1861. I recommend you download and read his book, “The Tannin Process”, it’s free on Google Books. Moreover, I recommend you read the real jewel, “Collodion Processes, Wet & Dry” 1862 by Thomas Sutton. That’s where my practice is mostly based. Sutton has been a game-changer for me in photography.

Three collodion dry plates ready to load into the holders.

Tannic acid is a preservative. It allows you to keep the properties of the silver iodide and silver bromide “active” over a long period of time. Think of it as AgI and AgBr hibernation. The drawback is exposure time. I average between 5 minutes and 20 minutes. You can go a bit shorter or a lot longer depending on the aperture and the quality of light. There are plenty of other dry processes, too. The Coffee process, The Oxymel process (honey and acid), the Fothergill process, the Collodio- Albumen process by Taupenot, etc. The tannin process is the most popular because it’s easy to do and the preparation is simple.

The quality of the plate will depend on iodides and bromides in your collodion. Sutton talks about the perfect “opaqueness” of the plates. I can get them almost perfect for what I do. I rate them at ISO 1.

If you’re working in the wet plate process, or have worked in the wet plate process, you’re 95% of the way there. I would encourage everyone that wants the freedom to travel to areas where a mobile darkroom is not possible to explore these processes - especially the tannin process. Again, you don’t need anything special if you’re working in the wet plate process - tannic acid and maybe some pyrogallic acid if you don’t have it already. Simple.

Platinum Palladium print. “Lightning Tree” from a collodion dry plate negative - I’m thinking about the fire burning near us. I consider all of my photographs as “sketches” for my ideas. Nothing is ever settled until it is - if you know what I mean.

The Lightning Tree

We’ve lived in the state of Colorado for 11 years now. We truly love it here. We’ve always been aware of droughts and wildfires. We both grew up in the Western U.S. And we did our research when we purchased our land 6 years ago. Last summer was our first full-time summer here. It was very wet. In fact, it rained every day in the afternoon all summer long. No problem with wildfires. It never crossed our minds. Now, it’s only May, no moisture and we’ve got a 1500+ acre wildfire burning just to the southeast of us. Like hurricanes, they name these fires. This is called, “The High Park Fire 2022”. It’s way too close for comfort. It really wakes you up. Talk about death anxiety and death denial, huh? We can still smell the fire and see the smoke. We’ve set our 26’ trailer house up and have been getting it prepared for evacuation. We can live comfortably in that for 2 weeks. I hope we never have the need, but it might be a long summer for wildfires here.

Collodion dry plate negative (white paper behind) and Platinum Palladium print (cropped). I’m looking at light here - I made this negative at about 0930 in the morning. I exposed for the shadow side of the tree. I like the heavy contrast and the way the tree is rendered. I like the shadows, especially of the limb in the foreground. I look at these like paintings. I also find the perspective interesting. I cut the print down to fit the scene. It looks great in the hand, I really like it.

Our mountain road is closed. They evacuated the people that live just to the south of us and for some reason, closed our mountain road off. We can come and go as we please, but you need to prove that you live on the mountain. Jeanne and I haven’t been off the mountain since the fire started. We have no need. We’re self-contained and can go for 2 weeks, or more, at a time without ever leaving our property.

Yesterday, I threw on the camera backpack (f/64 backpack) and grabbed some collodion dry plates and we headed up to our rock outcroppings on our land. It’s a treasure trove of interesting images. We found three “lightning trees” - trees that had been struck by lightning, burned, and died. Remember, we’re at almost 9,000 feet. In fact, where these trees are is 9,000 feet above sea level. From what I can see on our property, there’s never been a major fire here.

Collodion dry plate negative of “The Lightning Tree”. May 16, 2022 - Navajo Mountain.

I wanted to continue to play with the 90mm wide-angle lens. So I picked a tree and made this image. The negative is great. The lens does vignette at f/8 on the edges. I don’t mind. In fact, I ended up cutting the print to a square and it looks great. The theme of fire and nature is a constant now. I made a few plates and tried to juxtapose the old dead “lightning trees” with new, baby Ponderosa Pines that are growing in the rock outcroppings.

I made some Platinum Palladium prints, some Kallitype prints, and my first Oil print on Glass of this work. I got the first coat of brown inked on. I’ll let it dry and swell and ink again with some black ink for contrast.

Kallitype print, platinum toned. A small Ponderosa Pine emerging from a big rock. I know the digital snap doesn’t really translate that well, but gives you an idea. Kallitypes are really beautiful. The subtle detail you can get is really gorgeous.

Platinum Palladium print. Cascading rocks and dead fall trees. The perspective and texture is very appealing to me in this image. The way the lens draws your eye up to the tiny tree in the distance is really beautiful. The texture of the rocks are great too.

The first coat of dark brown ink. I’ll let this dry and then swell the gelatin again and ink it up with some black, it will add contrast, This is on a sheet of 10” x 12” x 2.5mm glass.

Swollen gelatin on glass - the matrix inked up.

Oil print on glass - backed with a piece of white paper. Fist pass with dark brown ink.