Gregory Crewdson said, "Every artist has a central story to tell, and the difficulty, the impossible task, is trying to present that story in pictures."

It’s always an interesting conversation when the topic of looking at photographs comes up. When I say “looking at” I really mean critiquing, analyzing, thinking about, and evaluating. Criticizing is not a bad word, in fact, it’s very beneficial if done correctly. However, it’s a much more complex process than it seems. There’s some deconstruction as well as an understanding of the context and the intention behind the image.

Morris Weitz identified major categories of criticizing in his study of Hamlet. He defined it as describing, interpreting, evaluating, and theorizing. Can you look at a photograph and not think about it in this way? Yes, of course, you can. However, you’ll miss a lot and maybe even miss the meaning and substance of the work - the good stuff. It’s like looking at a cover of a book and not reading it, or only reading the title. You’d miss a lot. The goal is to increase appreciation and understanding of the work.

THE NARRATIVE OR STORY

Without a foundation of some kind, nothing can stand. A body of work (photographs) or a single image need a foundation too. We call this a narrative or story. Without it, it’s very difficult for the viewer to connect to your work in any meaningful way. Yes, they can project their own memories and experiences onto an image, or set of images, and dream up anything they want in order to connect that way, but it should be your story, not theirs. It’s your work.

Maybe that’s not important to you. Maybe it’s enough for the viewer to like the technical aspects of the process you used or the content of the photograph; trivial stuff, weird stuff, cool stuff, bizarre stuff, nudity, etc. Maybe you feel it’s good enough that there’s an emotional response by simply looking at the image without having any information about it. It’s possible that you don’t even care if you have a story or not (most don’t). I can understand all of these positions. I get it. The question still remains, is this the best way or most productive way to make work or have someone view the work? I suppose it depends on your objective. Selling images, or commercial work, and expressing ideas, also known as fine art, are mutually exclusive. In other words; they’re water and oil. Rarely can you have both, but it does happen for a few. Artists like Sally Mann, Joel Peter-Witkin, Nan Goldin, etc. come to mind. For most of us, it’s one or the other. You either make pictures for someone else or you make pictures for yourself. I’ve been fortunate over the years to hit that magic scenario with a couple of exhibitions of my work. My time in Paris, France was very good. The work was all mine and it sold very well. But again, it’s rare. I choose to make my work as authentic and personal as I can. Regardless of selling it or not.

My goal has always been to share ideas, and information and make people think about my ideas, theories, and questions through my images. I want to tell a story about something I care about. William Klein said, “Be yourself. I much prefer seeing something, even if it’s clumsy, that doesn’t look like somebody else’s work.” Your work will be more “yours” approaching it in this way. Too much work is made in the style of emulation or imitation - it becomes derivative quickly.

RESPONSIBILITIES

Both the artist and the viewer have some responsibilities. They’re very different responsibilities, but they do have them. The artist has the responsibility of providing the viewer with an authentic narrative. The story, as abstract as it may be, or not, should give the viewer a chance to understand the context and intention of the artist. What is this work? And why was it made?

The viewer should approach the work looking for the narrative, or reason the work was made. It’s on them now, not the artist. I’m not saying that everything needs to be explained and justified. Not at all. There’s plenty of room for mystery and unresolved elements. And there should be. However, to even get to that point the aforementioned needs to happen.

CONCEPT & CRAFT

Irving Penn said, “A good photograph is one that communicates a fact, touches the heart, and leaves the viewer a changed person for having seen it. It is, in a word, effective.”

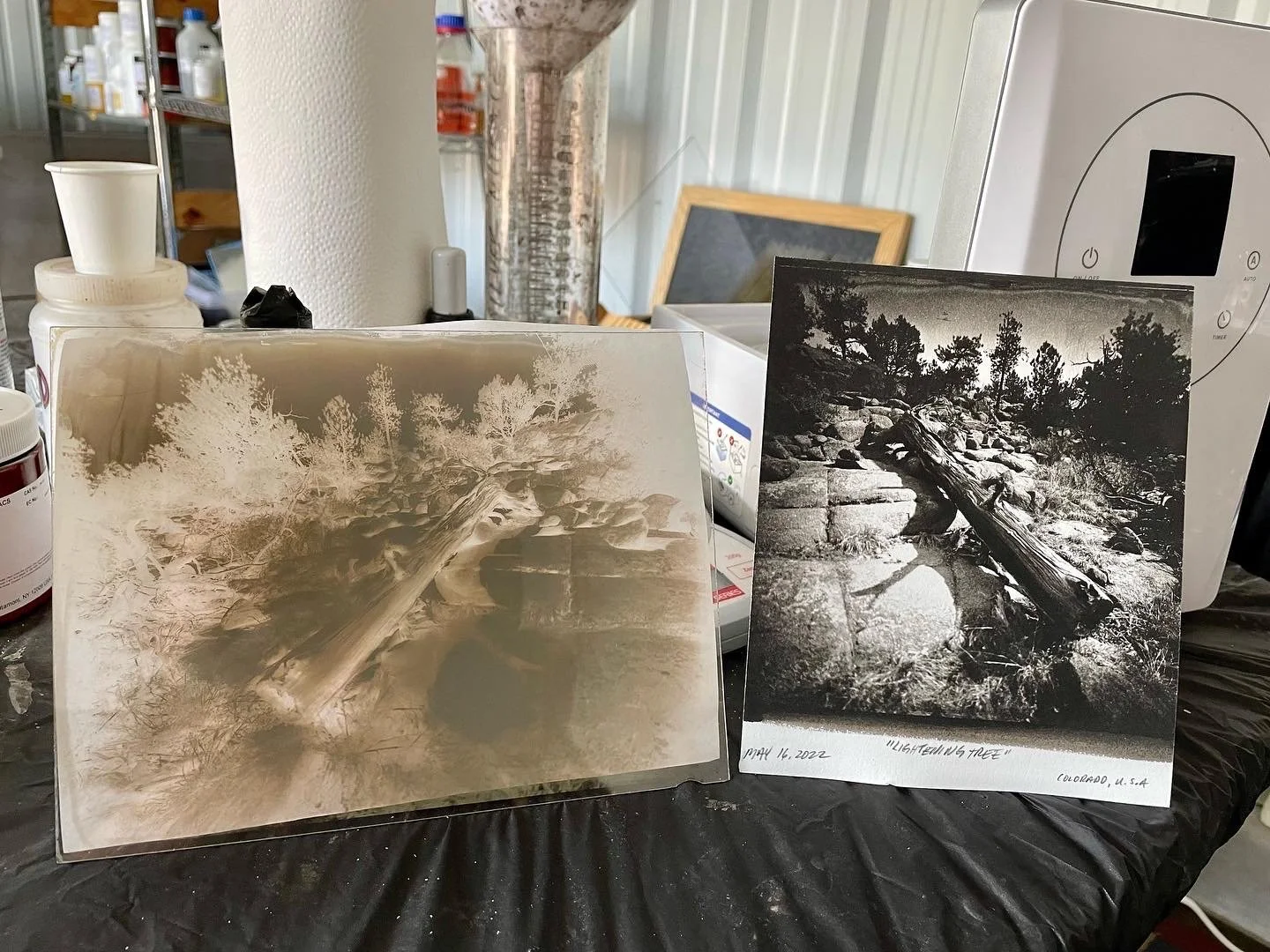

What do I mean by “concept and craft”? The concept is the story/narrative or reason the work was made - think context and intention. And the craft is how it was made - why the specific processes or materials were used and how they connect to and support the work.

The balance between concept and craft is important to make a successful body of work. When you’re involved in 19th-century photographic processes, the technical, or the processes, tend to lead. The process becomes more important that the concept. What I mean is that the fascination is usually on the technique, not the content of the image. Sometimes, the interest is pointed toward the minutiae; what optic was used or chemistry was used, or what lighting was used. Not even considering the really important ideas behind the image.

I believe that the process should support the work, not the other way around. Photographers today lean heavily on the technique. I understand that. It’s a way into a world where you’re virtually a blade of grass, just like the other 100,000+ artists and photographers out there. How do you distinguish yourself? How do you make yourself stand out? 19th-century processes tend to open doors and get viewers. Regardless of the content or the quality of the work. And without narrative. Social media has driven a lot of these trends. We tend to be superficial and shallow when it comes to evaluating and considering artwork of any kind.

AUTHENTIC NARRATIVE: A RARE THING NOWADAYS

What is an “authentic narrative”? That depends on who you ask. In my opinion, it would be defined as an artist that has used the Socratic method (so to speak) to examine what’s most important to express about a question, a concern, a love, a dislike, beauty, ugliness, politics, social issues, etc. that they have. This is something that will keep the artist creating until the work reflects a part of them in a true and authentic way. I don’t think art should really answer any questions, I’m not sure it even can. The power in art comes from asking questions. The narrative should reflect that. It has to be deeply connected to the artist.

Over the past 20 years, I’ve seen the wet collodion world go from a small group of dedicated artists to a large group of people looking for their 15 minutes of fame. I’m not saying that’s wrong, I’m simply stating facts. Not everyone shares the vision of making meaningful, personal work. True, authentic pursuits of telling a story are rare now. When I got involved in these processes, they were used as tools to tell stories in a unique and new way, a personalized way. Not so much anymore. There are a few people still working hard to be authentic and using these processes as tools, not as “made you look” gimmicks to get their photographs published, shown, or sold. They’re rare and few and far between. And don’t misunderstand me, there is absolutely nothing wrong with making commercial work in any process or medium. Making money is fine. The issue I have is when commercial work is called fine art. Again, commercial work is making work for someone else - usually for money. Fine art is making personal work about something that you are interested in or care about and are asking questions about. Usually, you are connected to it in a real way.

If this is a topic that interests you, check out this video I made a couple of years ago: Showing Your Work and Criticizing Photography: Three Things - it will give you more insight into my theories and ideas about making art.

“Of course, there will always be those who look only at technique, who ask ‘how’, while others of a more curious nature will ask ‘why’. Personally, I have always preferred inspiration to information.” — Man Ray