Since our big snowstorm hit last week, I’ve had some time to do some research and reading. I’m trying to consume everything I can about the Nuuchiu (“New-chew” means “Mountain People”) also known as the Ute that lived here. The past few days I’ve been reading about their “Circle of Life” belief. I’m very interested in both their cultural and spiritual beliefs. I would like that knowledge to inform my images and support the work.

They’re the only tribe in North America that doesn’t have a migration story. That means they’ve been here (in Colorado) for time immemorial, or “forever”. I struggle with the idea of this land being stolen from them (their land) and moved to reservations. I hope this project will elevate and honor them in some way, that’s my desire. I remember a George Carlin quote. He said, “Sometimes people say, 'Do I try to make audiences think? ' I say: 'No no no,' because that really would be the kiss of death, but what I want them to know is that I'm thinking." That really sums up what I want for my work. Even if people don’t like it, I want them to know that I think about these things - a lot.

For now, I’ve decided to call my project, “Nuuchiu” or “Mountain People”. Although it won’t have images of the people, it will contain a lot of what was most important to them. Their land, rock formations, sacred sites, trees, and plants. I’m interested in the symbology of these things. In other words, they are literal but I want to show them symbolically as well. Tying stories to the objects is the most important thing to me. Telling their stories as best I can with my own interpretation of the objects. I’m in no way claiming expertise on Native American culture or history. I’m an artist asking questions, that’s all. However, I do live here and I can feel what they saw, how they lived, and the beauty and mystery they found here for thousands of years.

The Circle of Life is a central theme of Nuuchui/The Mountain People. The Ute people have a unique relationship with the land, plants, and all living things. The Circle of Life represents the unique relationship in its shape, colors, and reference to the number four, which represents ideas and qualities for the existence of life.

The People of the early Ute Tribes lived a life in harmony with nature, each other, and all of life. The Circle of Life symbolizes all aspects of life. The Circle represents the Cycle of Life from birth to death of People, animals, all creatures, and plants. The early Ute People understood this cycle. They saw its reflection in all things. This brought them great wisdom and comfort. The Eagle is the spiritual guide of the People and of all things. Traditionally, the Eagle appears in the middle of the Circle.

The Circle is divided into four sections. In the Circle of Life, each section represents a season: spring is red, summer is yellow, fall is white, and winter is black. The Circle of Life joins together the seasonal cycles and the life cycles. Spring represents Infancy, a time of birth, of newness-the time of “Spring Moon, Bear Goes Out.” Summer is Youth. This is a time of curiosity, dancing, and singing. Fall represents Adulthood, the time of manhood and womanhood. This is the time of harvesting and of change - “When Trees Turn Yellow” and “Falling Leaf Time.” Winter begins for gaining wisdom and knowledge - of “Cold Weather Here.” Winter represents Old Age; a time to prepare for passing into the spirit world.

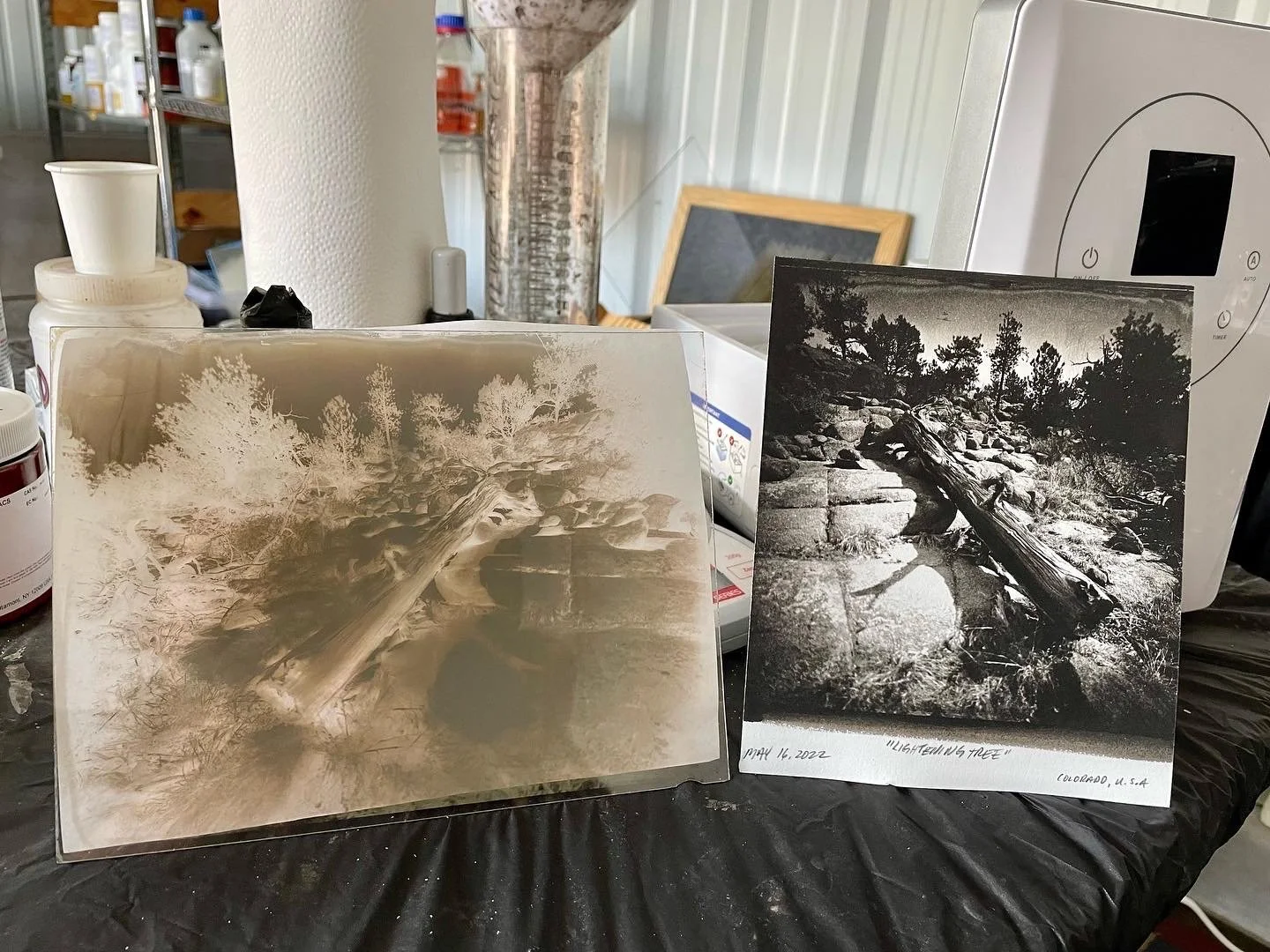

The “Circle of Life” - from a whole plate wet collodion negative - May 28, 2022 - Nuuchiu land, Colorado.

Whole Plate wet collodion negative - May 28, 2022 - Nuuchiu land, Colorado U.S.A.

Culturally Modified Trees. I’ll talk more about CMTs as my project evolves, but you can read about them here, a post I did almost a year ago talking about my project. From a wet collodion negative - May 28, 2022.